In March 2020, when COVID-19 first arrived in Zimbabwe, we decided to switch our research focus to study the unfolding implications of the pandemic in our rural sites across the country. We did not expect to continue for over two years. It required us to reinvent a way of doing research so that we got to understand how the pandemic affected lives and livelihoods as well as emotions, social relations and politics.

The pandemic was not one event: there were different phases, with intermittent lockdowns and fluctuating incident. At some points, particularly at the beginning, people were scared, fearful of what was to come. At other points, people were angry, frustrated that they could not get on with their daily lives, prevented from doing so by strictly imposed movement restrictions, curfews and bans on trading. At still other points, people felt relatively relaxed, confident in their own treatments and abilities to survive, dismissing the impositions from outside as irrelevant and politically motivated.

Too often studies of the pandemic are based on snapshots, at best a series of them. These studies were often done at a distance through phone interviews and recall. Such approaches have their worth, but they do not get at the experiences of living in a pandemic, and how strategies changed over time. Responses were quite contingent, reflecting a diversity of factors impinging at particular moments. And it was not only what people did, what they earned, how they responded, but also how they felt about it that framed the response.

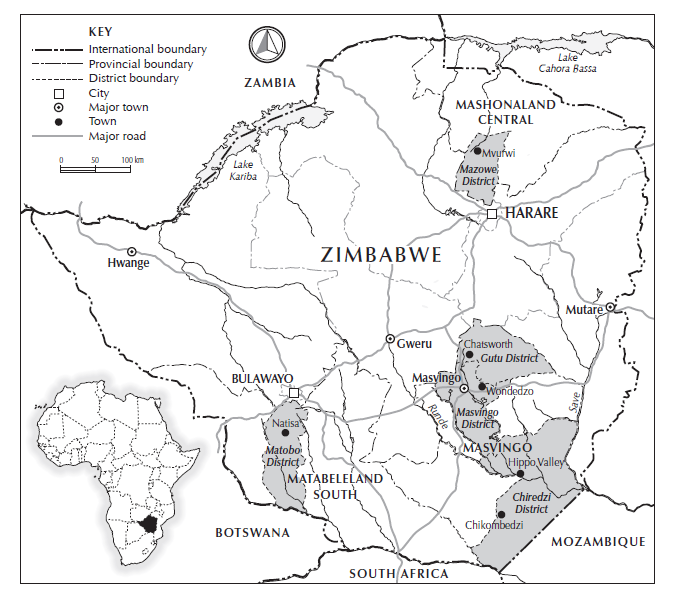

Over nearly 20 years, our work in Zimbabwe has focused on a number of sites across the country where land reform took place (see map). The research team largely lives and works in these places, stretching from Chikombedzi in the far south lowveld, to the sugar estates of Hippo Valley and Triangle, to Matobo in Matabeleland South where livestock are especially important to other mixed farming sites in Masvingo, both near the main town (Wondedzo) and further north in Gutu. Our final site in Mvurwi, a tobacco growing area not far from Harare, the capital, is a high potential area, where commercial farming dominates. Although no set of sites can be truly representative, our seven areas cover a wide range of contexts.

Our field team are all farmers and some earn other money from extension worker jobs with government, well-digging and other activities – including research. They know their areas well and the people there. Their contacts are excellent, both in the land reform sites and the small towns in the areas. They have their fingers on the pulse and are not external researchers separated from the pandemic. They had to experience it as everyone else did in their areas, experiencing the uncertainties, worrying about the lack of health facilities and dealing with illness and sometimes death over the past years.

At the beginning of the pandemic, we decided to write occasional blogs on what we found. The process involved the team documenting experiences, identifying themes, interviewing people and writing down quotes and case studies. The information was then relayed to the research team lead, Felix Murimbarimba in WhatsApp conversations. Photos from the field sites were sent too. Felix then compiled the reports and relayed them to Ian Scoones who was in the UK, prevented from travel due to the pandemic. He the put together a blog. In the end, 20 were produced starting in March 2020.

We did not have any prior questions, beyond finding out what was happening in each of the sites. We left each team member to probe and explore what was happening in each place: the stories, the gossip, the scandals, the innovations, the tragedies. This allowed an open-ended approach to the research without assumptions or biases. We were interested of course in how rural life changed, so themes of agriculture, land and livelihoods were central, and reflected our own professional foci and our past research. But as we went along there were particular themes that emerged.

The way people had to diversify was central, with small-scale mining for example being important in many areas, with important gender and age dimensions. Issues of politics emerged at different points in different sites, and everyone had a view resulting in much debate about the role of lockdowns, the value of vaccines and the influence of corrupt officials and more. As the pandemic progressed, we noticed innovations of different sorts – in some cases to get around the regulations, in others to develop local treatments for the symptoms of the disease. A rich picture emerged, one that would have been impossible through any other research approach.

As a real-time reflection on a pandemic from the standpoint of local participants, it is a unique record. The blogs have now been compiled in a short 160-page book, illustrated with colour photos from the sites. You can buy the book on Amazon (£12.72 for a paper copy, £1.25 for a Kindle version) or download it in high- or low-resolution versions here and here).

We have also produced two more analytical papers from the material, reflecting on cross-cutting themes. These include a paper on ‘narratives’ around the pandemic and how across three periods these narratives constructed the social and political reaction to the pandemic in rural Zimbabwe. The other paper published in BMJ Global Health looks at local resilience-building, and how adaptable livelihoods and local innovation contributed to the ability to survive in the face of an uncertain, unknown disease across our research areas. These two papers will be featured in the following two blogs.

The research team are Iyleen Judy Bwerinofa, Jacob Mahenehene, Makiwa Manaka, Bulisiwe Mulotshwa, Felix Murimbarimba, Moses Mutoko, Vincent Sarayi and Ian Scoones.

This blog was written by Ian Scoones and first appeared on Zimbabweland