Launched today in partnership between the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a new online platform, the Epidemic Response Anthropology Platform (ERAP2), building on the success of the award-winning work of the original Ebola platform (ERAP).

In light of the current Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) it is impossible not to reflect on the lessons learned from the epidemic in West Africa during 2014 to 2016. The initial international response by donor and humanitarian agencies faced resistance because it failed to take account of local customs and practices such as burials. There was a massive gap in knowledge of the local context, and a need for a social science and anthropological response.

As Dr Hana Rohan, Assistant Professor in Social Science for the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team, said: “During the West Africa Ebola outbreak there was an urgent need to quickly link emergency response workers with social scientists, to make sure communities were understood and listened to. Evidence from the original platform showed why Ebola could only be contained with the explicit involvement and active participation of local communities, what this might involve, and how it could be achieved.

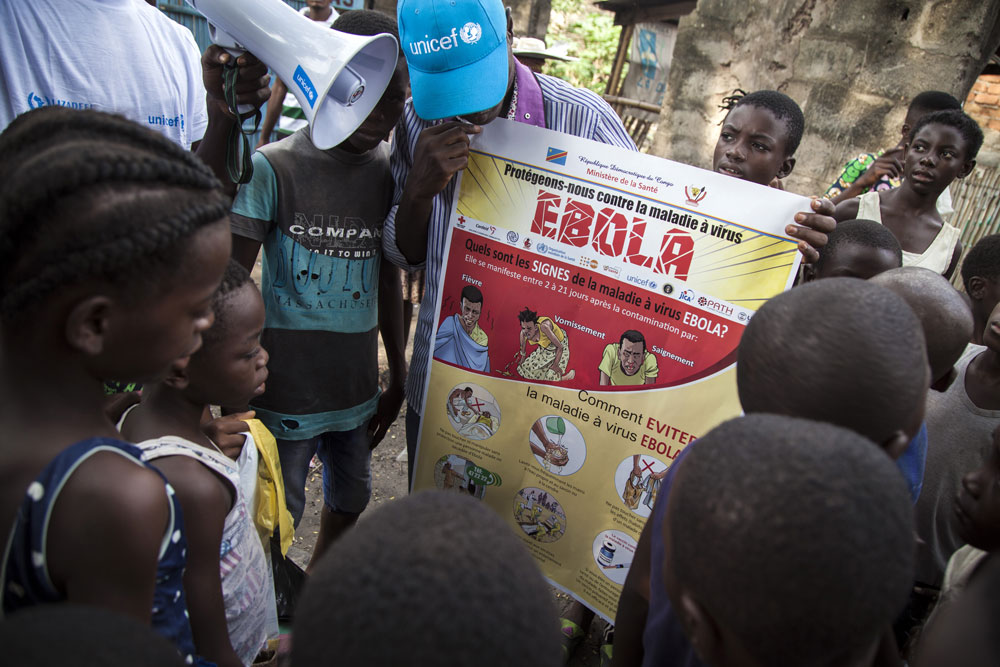

“The DRC is currently experiencing an outbreak of Ebola with recent reports suggesting that last week two patients were removed from the Ebola Treatment Centre and taken to church. This could potentially have led to further virus transmission and temporarily halted control efforts due to security concerns. This demonstrates how important it is that outbreak response is managed in a locally appropriate way. This new platform aims to help make sure this happens more, and quicker.”

ERAP2 is a resource to support a humane and effective response to epidemics. The aim is to promote evidence on the social dimensions of epidemics in different contexts and to improve the way this evidence is used in response planning. The new platform will work with, and build, networks of anthropologists and other social scientists with regional or subject expertise and connect them to policymakers, scientists and humanitarian response workers involved in responding to epidemics.

The new platform is supported by the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team, which is jointly run by LSHTM and Public Health England and funded by the UK Government. It also works closely with international partners on global health and humanitarianism, in particular through the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform, a partnership between UNICEF and IDS to strengthen the use of social science in emergencies.

It will showcase different types of evidence that will be readily available in one place, including journal articles; field reports; emerging syntheses of crises; briefings including expert opinions; blog posts and peer reviewed articles. These resources will reach across multiple issues: emergence and origins; transmission and spread; identifying cases and surveillance; reducing spread; engagement and communication; local sources of care and advice; clinical research; and recovery.

In a field dominated by medics, epidemiologists, virologists and other natural scientists, the original platform showed how valuable a social science perspective can be. During the Ebola crisis nearly four years ago researchers saw early on that it was more than a medical emergency. The epidemic was also a lens through which much that had gone wrong with development to date could be seen.

The work of the original platform highlighted the importance of long-term social science and anthropological research, and support for it – including funding. The rapid response that the platform was able to mount would not have been possible without the team’s years of anthropological and interdisciplinary research.

Following in the footsteps of the original platform, it is hoped that ERAP2 will become a focal point for social science evidence and advice, helping hundreds of anthropologists, social scientists, and practitioners on the ground to mobilise and provide much needed insights into the social contexts of resistance and reticence, rumours, burial practices, care for the sick, the development of vaccines and much more.

This news story originally appeared on the Institute of Development Studies website.