To date, the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak has caused over 3,000 deaths, and we are at the critical threshold of global pandemic. Meanwhile, at the centre of this outbreak, the city of Wuhan has been in total lockdown for over a month and the number of deaths and new cases is finally beginning to gradually decrease. It is time to reflect on what can we learn from what happened at the centre of this crisis in Wuhan, from the social science perspectives. This will be critical for the preparedness for other low and middle-income countries facing a looming COVID-19 outbreak.

First, let’s consider information disclosure, transparency and public behaviour management, which are closely linked to the political culture and decision-making processes. In China’s case, the early warning signs in late December among frontline doctors were treated as rumours and suppressed first by their employers (hospitals) and then by the police, so the chance for earliest response slipped away due to the attempt to control information.

In contrast, after the outbreak was acknowledged, the government decision of a total lockdown of Wuhan city was announced to the public ten hours before taking effect, without any attempt to control expectable public anxiety or fear. Such decisions led to millions of people fleeing the city, or rushing into hospitals, pharmacies or even supermarkets for medical advice or supplies in those ten hours. It consequently caused numerous new infections in the days afterwards.

‘Killing virus’ rumours

Meanwhile, different rumours about the ‘killing virus’ spread rapidly across the internet, fuelling fears and anxieties. Hence, social science experts on communications and public administration will play an important role in revealing what is the best strategy to ensure information transparency, while containing harmful fake news, and managing communications to minimise public panic and panic-induced reactions.

Second, the outbreak in Wuhan shows the crucial role of sufficient and timely material supplies for combating the virus. I recently interviewed frontline doctors and nurses working in Wuhan and they reported that in Wuhan it is estimated that around 20-25 percent of people infected with COVID-19 require intensive medical care in the hospitals at some point. This means that an outbreak with large numbers of patients would stretch a healthcare system to the brink if there are not sufficient beds, medical equipment, and protective gear for the doctors and nurses.

Organising and distributing medical supplies

Wuhan is a city with over 30 top-quality public hospitals but the whole system still nearly collapsed due to a lack of infrastructure, equipment, medical personnel, and other resources. How can such massive material flows be managed and by who? China, as an authoritarian regime relies on strong a state to organise and distribute these supplies, but this appears to have some obvious advantages and disadvantages.

On the one hand, the fact that can large-scale infrastructure like contemporary hospitals can be constructed in days, and expensive medical equipment such as ECMO machines can be imported and delivered (with over 100 now in Wuhan alone) shows how efficient this state-led system can be.

On the other hand, it shows that small materials like surgical masks, goggles and medical suits cannot be effectively managed in this total state system, and it seems that a lack of strong civil society groups in China makes distribution of large amounts of donations, purchases and distributions particularly challenging. As a result, in the first two weeks of the outbreak, many frontline doctors and nurses were not even well protected when they were trying to save lives in the emergency rooms. Their strong professional ethics is heroic and admirable, but such a situation has led to a large number of infections among medics. Therefore, studies of state-civil society relations, logistic supply and production systems are particularly useful to learn lessons in a crisis like this.

Longer-term impacts on social inequalities

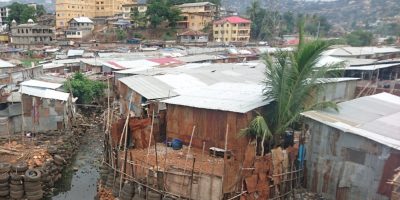

Lastly, the outbreak has tremendous implications for social inequalities, as some social groups will be particularly vulnerable during and after the crisis. Low-income groups will be hit hardest economically if the lockdown persists and a freeze on economic activities, such as factory closures continue for months ahead.

Poor households have smaller flats or fewer rooms to share if one family member is infected, making effective home isolation almost impossible. They lack information and often are the last group to think about protection, seeking it when all the gear such as facemasks and hand sanitiser is already running out in the market. In fact, in China’s case, the capability of getting some medical equipment during the crisis is often dependent on good social networking or social capital.

They are often misled by fake news or rumours that lead to wrong and dangerous behaviours (such as rumours that some herbal medicine are useful, which led to another mad rush of people to the pharmacies, causing yet more infections). More often, they are simply forgotten during the crisis, such as the large numbers of people in Wuhan Mental Health Centre and prisons were infected, which was not even noticed until very recently. It is almost certain that these people on lower incomes will face particular hardship even after the crisis. Therefore, how to build up protective capacity during the crisis and resilience afterwards among these groups requires immediate research inputs on issues around social justice and social policies.

At the time of writing this there are over 2132 recorded deaths in Wuhan due to the Covid-19 outbreak. Our hearts and thoughts are with the victims and their families, and with those who are still struggling to survive the crisis – particularly those heroic medics on the frontline. As social scientists, what we can contribute is the use of knowledge to make sure the world is better prepared, and to help those whose livelihoods are completely devastated by coronavirus to rebuild their lives in the future. Wuhan, Jiayou!

Dr Wei Shen is a political economist and research fellow at the Institute of Development Studies. Dr Shen wishes to thank the doctors and nurses from Wuhan hospitals who he interviewed over the phone to inform this article.

This blog originally appeared on the Institute of Development Studies website.