In many settings, people with disabilities face multiple and complex layers of environmental, societal and structural barriers. These barriers can lead to them being disproportionately harmed, neglected and excluded during humanitarian and other emergency responses.1–3 This is especially evident in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Nepal and other South and Southeast Asian nations.4 Limited awareness of the needs of people with disabilities, entrenched social stigma, and inaccessible infrastructure can exacerbate the challenges they face in emergency situations. In addition, there has been little preparation and planning to make disaster and emergency planning disability inclusive.3,5,6

This brief explores disability in the context of humanitarian and public health emergencies in South and Southeast Asia. Its focus is on Nepal, but the principles are universally relevant and can be adapted for any context. It is intended for stakeholders in government, civil society and the humanitarian sector. It aims to support stakeholders to better understand how structural inequities, alongside social and cultural norms and practices, exacerbate the marginalisation and exclusion of people with disabilities in emergencies. This brief presents examples of good practice for disability-responsive humanitarian and emergency planning and intervention. It also provides key considerations for actors aiming to support greater inclusion of people with disabilities in response.

This brief draws on evidence from academic and grey literature, and from open-source datasets. It was authored by Obindra Chand (HERD International, University of Essex), Katie Moore (Anthrologica) and Stephen Thompson (Institute of Development Studies (IDS)), supported by Tabitha Hrynick (IDS). This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

Key considerations

- Involve people with disabilities in humanitarian action and emergency response. Engaging with civil society, especially organisations of persons with disabilities (OPDs), can support the meaningful participation of people with disabilities. This should be across all stages of programme planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and peacebuilding activities.

- Ensure disability inclusion across emergency services. These include shelter, food provision, transportation, emergency health, safe water and sanitation services (including for continence).

- Ensure in-crisis adaptations to regular services are disability inclusive. People with disabilities must have continued access to regular services, including alternative education and health services, and equipment necessary for their wellbeing.

- Tailor communication. People with disabilities may require adapted information on what to do to protect themselves and access support. Identify and utilise contextually relevant sign languages and Braille systems. Use audio and captioned media, and plain language and Easy Read materials. Engage carers and support networks to reach those unable to use these or other communication methods.

- Provide protection from physical, emotional and sexual abuse. People with disabilities face heightened risk of abuse because they are often more isolated and have less access to protection services – especially if they are displaced or separated from support networks. This is a particular concern for women and children with disabilities.

- Recognise and respond to diverse needs. People with disabilities have different types and degrees of impairment. Disability may also intersect with other aspects of identity (e.g., gender, age, income) to shape individual vulnerability. Ensure interventions support the diverse needs of individuals with different identities, backgrounds and impairments.

- Recognise and support carers of people with disabilities. Many people with disabilities depend on care from family members, friends or organisations in their communities. During emergencies, people involved with providing care must be supported so that they can continue caring for people with disabilities, and for themselves. The gendered nature of informal caregiving roles must also be considered – women are more likely than men to take on this work.

- Gather more and better data and information. More data about people with disabilities are needed to support crisis preparedness and response. These data should include internationally comparable and disaggregated quantitative data (by disability, sex and age) and context-specific qualitative data (e.g., diverse needs, capacities and priorities of people with disabilities). Engaging social scientists and affected communities to support knowledge in this area is critical.

- Ensure planners and responders are accountable to people with disabilities. Although the importance of inclusive programming is increasingly understood, challenges to effective implementation remain. Information on ways to improve this can be gathered by different approaches. Implementing and supporting accountability mechanisms, including intervention and data monitoring, is one approach. Another is to set up ways for people with disabilities to ask questions and express concerns about responses.

- Advance day-to-day disability inclusion. Address everyday barriers by enhancing infrastructure, transport and communication systems to be disability inclusive. Also address issues of poverty, economic exclusion and isolation, which disproportionately affect people with disabilities. Support and work with civil society, especially OPDs, to achieve sustainable change.

- Enhance societal understanding of disability. Promote human rights-based and holistic understandings of disability among decision-makers, humanitarian teams and the public. Emphasise how social, cultural and environmental factors contribute to the disablement of people. Aim to counter dominant understandings that medicalise and individualise disability, and which reinforce notions of people with disabilities as objects of charity.

- Counter disability-related stigma. Avoid negative or stereotyping messages and images that could exacerbate stigma experienced by people with disabilities. Avoid perpetuating, and aim to actively counter, still common views of disability as a punishment for sins. Some groups may be at greater risk for stigma, such as women and girls with cognitive or psychosocial disability, and people from ethnic or religious minority groups.

Humanitarian emergencies and impact on people with disabilities

Context of people with disabilities in South and Southeast Asia

About 1.3 billion people, or 1 in every 6 people worldwide, have a disability.7 In the Asia and Pacific region more specifically, more than 700 million people are estimated to have a disability.8

People with disabilities are not inherently vulnerable but rather made vulnerable by social and contextual factors that create multiple and complex barriers. These factors may include physical or communication infrastructures that do not accommodate their needs, and gaps in social protection systems to protect people with disabilities. Discriminatory attitudes towards people with impairments are also pervasive in South and Southeast Asia.9,10 These barriers restrict their full participation in society and limit their ability to live healthy, dignified lives.

The type and severity of an individual’s disability may also intersect with other aspects of their social positioning, including poverty, gender, education level, social support network, caste, ethnicity and religion. Age is another critical factor; older people are disproportionately affected by disability and are particularly neglected in humanitarian and emergency responses. Together, these structural and sociodemographic factors can compound an individual’s risk.

People with disabilities are at significant risk of being left behind in development and humanitarian processes without specific action to ensure their inclusion.6

Governments in South and Southeast Asia have adopted legislation and policy demonstrating a high-level commitment to advancing the rights of people with disabilities. Over the past decade, all Southeast Asian governments, except Timor-Leste, have ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).9 Article 11 of this Convention indicates that states are responsible for taking all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of people with disabilities, including during natural disasters, conflicts and public health emergencies.

Asian and Pacific countries have also ratified the Incheon Strategy (2012),11 which set out regionally-agreed, disability-inclusive development goals. A main goal is to include the promotion of participation of people with disabilities in political processes and decision-making. Another is to take action to ensure disability-inclusive risk reduction and management during humanitarian emergencies and disasters. The Dhaka Declaration 2015+1 (2018) has also been adopted by many countries in the region and provides a practical guide to support the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015) calling for inclusion and meaningful participation of people with disabilities in all aspects of disaster risk management programming.12,13

Disability inclusion in humanitarian and emergency response

During humanitarian crises, people with disabilities remain among the most in need of assistance because crisis conditions compound the pre-existing social inequalities and resulting vulnerabilities they face in day-to-day life. In addition to simply missing out on humanitarian assistance, people with disabilities may also face increased risk of violence, exploitation or abuse.14 Mortality rates among people with disabilities during crises may be up to four times higher than those among the general population.15

The way traditional humanitarian assistance programmes are designed and delivered may worsen the inequalities, vulnerabilities and risks experienced by people with disabilities.16 For example:

- Lack of awareness and capacity of response teams can lead to the inadvertent exclusion of people with disabilities (Box 1).16,17

- Critical emergency services may be inaccessible as the additional needs of people with disabilities are often not considered during design and delivery phases. These services can include emergency health, sanitation, hygiene, shelter, food, water, safety and security.

- Day-to-day, disability-specific services may also become inaccessible or reduced. These might include rehabilitation services, services for chronic diseases that may contribute to a person’s capacity to function, access to assistive devices (e.g., wheelchairs, prostheses, crutches, hearing aids, feeding products), access to continence and menstrual hygiene support, and access to health information.

Box 1. Absence of data and information is a critical problem

A profound challenge to the delivery of equitable humanitarian action and emergency response is the absence of reliable data. This is a critical and persistent problem. Humanitarian responders often lack the most basic information about people with disabilities, including the number of people with disabilities and their needs; the barriers and risks they face; their capabilities, views and priorities before, during and after an emergency; and how they are affected by a crisis. This absence of data renders people with disabilities invisible. Responders may not be aware that they are inadvertently excluding people with disabilities, and organisations are left unable to deliver assistance that meets the needs of people with disabilities.

Source: Authors’ own unless otherwise stated.

Failure to include and consider people with disabilities throughout the planning and programme cycles translates into failure to address the specific barriers placing them at risk, including inequitable access to protection and assistance. Understanding the barriers that contribute to the exclusion of people with disabilities is essential for identifying gaps and operationalising inclusive policies, frameworks and guidelines in complex emergencies.

Another challenge for disability inclusion in humanitarian and emergency response is responding to the diverse needs of people with disabilities. People with disabilities are not a homogeneous group, and their needs differ depending on the type and severity of their impairment, as well as other aspects of their social position and context. Disability-inclusive humanitarian and emergency responses need to ensure that this is addressed within the planning process.

Disability-related stigma can also directly hinder involvement of people with disabilities in the planning, implementation and monitoring of response efforts. This varies by country and even within countries and between social groups.

Meaningful inclusion of people with disabilities in humanitarian action remains rare. This is despite the ratification of the UNCRPD and a broad shift towards social and rights-based approaches to understanding disability, and the promotion of participatory approaches (see below). There are several reasons for this lack of meaningful inclusion: the failure to recognise people with disabilities as actors in response efforts; the limited capacity of humanitarian actors to implement guidelines and promote disability-inclusive humanitarian action; and the lack of systematic integration of disability inclusion into global agendas.16

From the ‘medical’ to the ‘social’ model of disability and rights-based approaches

Disability has been and continues to be widely understood in many settings through a medicalised lens. The ‘medical model’, which emerged in the early 20th century, focuses on the diagnosis of an abnormality due to physical or psychological deficiencies intrinsic to an individual who, in turn, is framed as in need of medical intervention. This model emphasises the impairment and limitations of an individual, and frames disability as deviation from ‘normal’ traits and characteristics. This model also emphasises a need to fix or eliminate ‘defects’ for an individual to have an improved quality of life, while also reinforcing notions of their dependency on others for charity.18

In contrast, the ‘social model’ of disability emerged in the 1970s largely through the work of activists, and it has grown in influence. This model downplays the individual level and emphasises that disability is constructed by the social and political environment in which it exists. For instance, the model recognises that people with impairments are ‘disabled’ by institutional, legal, physical and other systemic barriers, as well as negative attitudes and social exclusion.18

Rights-based approaches to disability have also emerged to emphasise accessibility, participation and choice for people with disabilities, as in the UNCRPD.

Despite enshrinement of the social model and human rights approaches to disability in the UNCRPD (and other national legislative and policy provisions), significant legal and policy gaps remain. Social norms and beliefs about disability also continue to be rooted in the medical model and through a charity lens. People with disabilities are frequently framed as ‘beneficiaries’ or objects of charity. This fails to address attitudinal and environmental barriers preventing them from fully participating in society on an equal basis with others. Stigma and shame associated with disability are also reinforced through the charity model, particularly when attributed to cultural beliefs that regard disability as punishment or penance for sins in past lives, bad karma or the will of God – common across South and Southeast Asia.10

To ensure the inclusion of people with disabilities in South and Southeast Asia, in both daily life and emergencies, an integrated understanding of disability is needed. A ‘biopsychosocial’ approach takes into account the individual level (and the diversity of needs between individuals with different forms of impairment) and how this interacts with the social context.19 How disability is understood, particularly by government authorities and aid workers, but also by communities, has implications for how or if people with disabilities are supported and included.

Disability and intersectionality

Intersectionality refers to the interaction of an individual’s multiple social characteristics, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, occupation, level of education, ethnicity, caste and disability.20 People with disabilities can be disadvantaged across multiple characteristics, exacerbating the challenges they face. These challenges can become even more complex during humanitarian emergencies.21

For example, in LMICs people with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty.22 Their limited access to financial resources can prevent them from accessing critical resources and services (e.g., food or transport) day-to-day, let alone during an emergency.

Disability and gender also interact in disadvantaging ways. People with disabilities, and particularly women and girls, are often at higher risk of physical, emotional and sexual abuse.23 These groups are often more isolated and have less access to protection services, particularly if they are displaced during a crisis. Displacement is also hugely disruptive to social networks and may break up families. When there is a need for emergency evacuation, such as when an armed conflict arises, many people with disabilities are at higher risk of being left behind and isolated from carers they depend on.24

As both disability and emergency situations are multi-layered and context driven, social scientists, particularly anthropologists, can support better contextual understandings of the specific and multilayered challenges faced by people with disabilities experiencing crises. A thorough consideration of sociocultural, political and historical factors that influence disability in a given context can help to explain how disability is created, perpetuated and exacerbated in crisis settings.25

Case study: Nepal

In Nepal, people with disabilities face numerous challenges in daily life, including lack of access to basic healthcare, societal stigma, and discrimination.26 This has resulted in poorer physical and mental health outcomes compared to people without disabilities.27 Conflicts, disasters and public health emergencies have exacerbated these challenges (Box 2).3,28,28

Earthquakes and other natural disasters, conflicts and crises have not only disproportionately impacted people with disabilities in Nepal, but they have created new disabilities, particularly through serious injury.28,29 The Nepalese Civil War, for instance, led to the disablement of thousands of people, many of whom continue to face social exclusion and have not had access to justice.30,31

Box 2. Conflict, disaster and health emergencies in Nepal

Nepal is considered one of the world’s most disaster-prone countries. Here, earthquakes, epidemics, fires, floods and landslides have been identified among the greatest disaster risks to people with disabilities.28 The country also has a history of conflict related to political instability, which has had humanitarian implications. For example, the decade-long Nepalese Civil War (1996-2006) resulted in 13,000 deaths, 1,200 disappearances, the injury or physical disablement of 8,000 people, and displacement of over 100,000 people.32,33 The political instability in the wake of the war also negatively impacted the country’s disaster preparedness and response capacities. This was made evident in the many missteps made during the response to the 2015 Gorkha earthquake in which nearly 40% of people with disabilities were excluded from relief and recovery programmes.34 This exclusion was due to the location of relief stations, lack of inclusive communication and people losing their official disability cards during the disaster, which meant support was denied.35

Source: Authors’ own unless otherwise stated.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal, a survey of people with disabilities found that over 45% had experienced interrupted access to their regular health services during lockdown, and 36% reported not receiving adequate health services.3 This raised critical questions about health equity, inclusion and accessibility of services for people with disabilities. This interruption of care also represented a threat to the realisation of national and global goals for rights to health for all.36,37

Information on people with disabilities in Nepal – both at baseline and in the context of humanitarian emergencies – remains inadequate. Official government statistics suggest people with disabilities constitute just 2.2% of the total population.38 Disability activists consider that this is an undercount resulting from disability-associated stigma and limited in-country data collection capacity.39 Indeed, an independent national survey estimated 15% of the population has a disability.27

Under The Act Relating to Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2017),39 the Nepali government created an official classification scheme for disabilities with 10 categories and four degrees of severity. The 10 categories are:

- Physical disability

- Disability related to vision

- Disability related to hearing

- Deaf-blind

- Disability related to voice and speech

- Mental or psychosocial disability

- Intellectual disability

- Disability associated with haemophilia

- Disability associated with autism

- Multiple disabilities

Severity ranges from ‘mild’ (able to perform daily activities and participate in social life if a barrier-free environment is provided) to ‘profound’ (difficulty performing daily activities even with the help of others).40,41

Disability in the policy landscape of Nepal

Despite ongoing challenges faced by people with disabilities, Nepal has made policy efforts to address the needs and concerns of people with disabilities, both during ‘normal’ life and under emergency conditions, especially in recent years (Table 1).

| Table 1. Disability in policy in Nepal over time | |||

| Policy/legislation | Year | Description | |

| Protection and Welfare of the Disabled Persons Act42 | 1982 | An early policy establishing free medical examinations for people with disabilities. | |

| Ratification of the 2007 United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD)43 | 2010 | Article 11 of the Convention states that signatory countries are responsible for taking all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of people with disabilities in situations of risk, including humanitarian emergencies and natural disasters. | |

| Accessible Physical Infrastructure and Communication Services Directive for People with Disability 201344 | 2013 | Indicated public places must be accessible both physically and in terms of communication for people with disabilities, with minimum standards, specifications and technical requirements. | |

| Article 18 of the Constitution of Nepal36 | 2015 | States that no person shall be discriminated against because of their sociodemographic characteristics. | |

| Disaster Risk and Management Act45 | 2017 | Adopted after two initiatives: international Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030), which specifically called for disability inclusion to be integrated into disaster management;13 and Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action of 2016, which detailed how action inclusive of people with disabilities was needed across all planning and implementation of humanitarian programmes.46 | |

| The Act Relating to Rights of Persons with Disabilities39 | 2017 | Further clarified the right to security, rescue and protection for people with disabilities with priority during emergencies, disasters and armed conflicts. The Act also made the government responsible for appropriate arrangements and legal actions to reduce the unequal burden on people with disabilities and promote equity and justice. The Act indicated the need for disability-inclusive emergency and disaster plans, preparedness programmes and interventions. | |

| Health sector emergency response plan: COVID-19 pandemic47 | 2020 | Stipulated quarantine facilities be designed to meet the needs of vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities, and that risk communication be developed in accessible formats suitable for people with a range of disabilities.

Guidance for disability inclusion in regular health services has also been created.48 |

|

Source: Authors’ own unless otherwise stated.

Social protection for people with disabilities in the form of an allowance scheme has also been in place since 1996. This entitles people with disabilities to cash transfers according to the official classification of the severity of their disability (indicated by colour-coded official ‘disability cards’). The cash transfers range from about 6USD to 19USD per month. People disabled during the civil war – and their caregivers – are covered by a special provision and are entitled to significantly more – about 60USD a month.35 Reach of this programme is thought to be significantly limited, at less than 40% of identified people with disabilities in Nepal – a number which is itself thought to be a significant underestimate.49

Civil society engagement and initiatives

In addition to official policy, legislation, and endorsements of international charters, civil society has also been active in the country. In a study of post-conflict fragile states, researchers found that ‘intense involvement of local organisations and user groups’ and a strong broader civil society were critical to the establishment and sustainability of rehabilitation services for people with disabilities in the wake of the civil war.50

More recently, the National Federation of the Disabled – Nepal (NFDN), an umbrella association of organisations of people with disabilities (OPDs) in the country, developed and promoted guidelines on disability-inclusive COVID-19 responses.51 This initiative brought the government’s attention to the importance of ensuring public health measures mitigated the unequal impact of COVID-19 on people with disabilities. In 2020, the Atullya Foundation, an OPD, in coordination with the government of Nepal, published the Disability Inclusive Get Ready Guidebook outlining strategies to mitigate the impact of disasters on people with disabilities, including loss of life and property.28

Limited implementation of the disability-inclusive policy agenda

Despite the policies and legal frameworks in place to support disability inclusion in Nepal, they have not been implemented effectively.52 A 2020 situation report indicated that people with disabilities in Nepal are more likely to experience poverty and difficulty finding work (especially women), and less able to access formal education and health services, especially in rural areas.35

Other evidence points to a persistent lack of accessible infrastructure and communication. For example, an accessibility audit of public places (e.g., government buildings, public parks, open spaces, roads) in the Kathmandu valley found most were inaccessible, some only partially accessible, and none fully accessible for people with different types of disabilities.53

Such shortcomings, along with inadequate planning, have had consequences for people with disabilities during emergencies. For example, following the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, half of the people with disabilities entitled to emergency cash transfers did not receive them because they were unable to reach the distribution points or because they lost their disability cards in the disaster.35

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, over 41% of people with disabilities knew little about the pandemic, while 6% were completely unaware of the pandemic due to lack of accessible information.3 The Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) did, however, integrate sign language interpretation into daily media updates about the COVID-19 situation in the country. Also, the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division (EDCD) developed a short video clip to promote awareness and access to COVID-19 prevention and control among people with disabilities.39

Experts have also suggested that despite the legal differentiation of types and severity of disabilities in Nepal, challenges remain in addressing the diverse needs of all people with disabilities. The categories still fail to reflect the specific needs of groups, such as wheelchair users or amputees.52

The reasons for inadequate implementation of the disability-inclusive agenda are numerous. Limited understanding of disability and of the concerns of people with disabilities in Nepal remains persistent. Social stigma also remains a problem. Certain groups of people with disabilities are particularly stigmatised and marginalised; these groups include as women and girls with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities, sexual minorities, people with autism and people from ethnic minority groups including Dalits, Madhesi and Muslim communities.35

Limited understanding could also be related to a lack of information, such as disaggregated data on disability that could be used for developing more effective disability-responsive programmes and plans.52 There is also a lack of effective monitoring mechanisms and political will to address the issues and concerns of people with disabilities.

Good practice for disability-inclusive humanitarian and emergency planning and response

There is an urgent need for disability-inclusive humanitarian and emergency response planning to address the marginalisation of people with disabilities in society, and the disproportionate risk and vulnerability experienced during humanitarian emergencies.54 The COVID-19 pandemic has been a global wake-up call because people with disabilities have been among the most affected.55,56 This section outlines good practice to support disability-inclusive humanitarian action in South and Southeast Asia, although the principles are universally relevant and can be adapted for any context.

International-level frameworks, charters and guidelines provide solid foundations upon which to build in the region. The UNCRPD, for example, describes the rights of people with disabilities to ensure protection and safety in situations of risk, including during humanitarian crises.43 The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) – the global humanitarian coordination forum of the UN – has established the Guidelines on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action to ensure people with disabilities are effectively included and considered in humanitarian situations.57 The guidelines suggest a twin-track approach combining inclusive mainstream programmes with targeted interventions specifically designed for people with disabilities.55

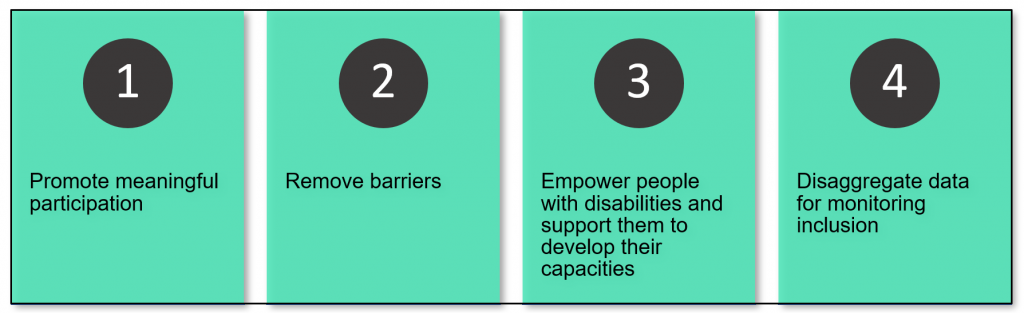

The IASC guidelines also promote four ‘must do’ actions to ensure that people with disabilities are successfully included in humanitarian and emergency responses (Figure 1). These actions provide practitioners with groundwork upon which to develop more concrete and situation- and context-specific plans and interventions. To be effective, every stakeholder in every sector and all contexts must take all four of the actions. Each action area is detailed below.

| Figure 1. ‘Must do’ actions to include people with disabilities in humanitarian responses | |

|

|

Source: Authors’ own. Created using information from IASC (2019)58. CC BY 4.0.

Promote meaningful participation

Involve people with disabilities. People with disabilities must be central to disaster planning, preparedness and recovery (including peacebuilding). They must be considered equal partners in these processes and not treated just as service users.59 Further still, people with disabilities with different characteristics should be consulted to ensure the needs of all people with disabilities are met. Their meaningful participation can support programming to be more sensitive to the needs of people with different types of impairment and who face multiple layers of disadvantage due to the intersection of their disability with other characteristics (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity, caste). In the wake of conflict, there can be a tendency to focus on the needs of those disabled by associated violence, but while this is important, inclusion of all people with disabilities is critical.

Collaborate with civil society. Collaboration with OPDs can help facilitate meaningful involvement and ensure the range of specific risks people with disabilities face are addressed.60 Involvement of OPDs should happen nationally and locally to ensure disability-inclusive information services and support are widely available during a crisis. Non-government organisations (NGOs) that work on disability inclusion alongside other priorities may also have a role to play in promoting meaningful participation.61

Learn from the lived experience of people with disabilities. Learning from the perspectives and lived experiences of people with disabilities can help develop nuanced, contextual understandings of their needs, requirements and challenges, and inform innovative approaches to navigating crises more broadly. The UN recognised that people with disabilities have experience adapting to isolation and alternative working arrangements, which provided valuable insight during COVID-19.62

Remove barriers

Health information, the physical environment, communications, technologies, and goods and services associated with crisis response need to be accessible. Failure to ensure this access may result in people with disabilities being unable to take necessary decisions or reach services on an equal basis with others.62

Ensure inclusive communication. Emergency plans and crisis-related information relating to prevention and response must be shared and communicated in diverse and accessible formats to all stakeholders who may need to use them.59 Local sign languages, audio, captioned media or Braille versions of information may be needed (Box 3). The information may also be needed in Easy Read or plain language formats. Where possible and appropriate, information about crises should support two-way communication and include opportunities for people with disabilities to raise concerns or ask for further clarification.60

Box 3. Distinct communication systems

It is important to recognise that individual countries, and even subnational regions, towns and villages within countries may have their own sign languages and variations of Braille communication systems. For instance, many countries in South and Southeast Asia, including Nepal, India, Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia, have their own distinct sign languages. Some village-level sign languages identified in Nepal include Ghandruk, Maunabudhuk–Bodhe, Jhankot and Jumla sign languages (UNESCO).63 Some people with disabilities may not be able to communicate in any formally recognised sign or tactile language. It is particularly important to engage their carers and household members who can communicate with and support them, to ensure they have critical information in an emergency. Touch-to-touch languages for people who are deaf-blind may be under development in Nepal.64

Source: Authors’ own unless otherwise stated.

Leverage digital technology inclusively. Technologies (such as mobile phones) have the potential to make information sharing during crises more equitable, but careful consideration is needed to ensure digital systems are disability inclusive and not the sole source of information.65

Address multiple needs through sector-specific barriers. Sector-specific barriers, such as in health and education, may also require specific considerations. For example, women with disabilities may face particular social and cultural barriers accessing sexual and reproductive health services, and these may be more difficult to access during crises. Particular attention is also needed to overcome barriers that may limit children or students with disabilities from accessing learning; alternative teaching arrangements may be needed, for example. Learning from at-home education provision during the COVID-19 pandemic can be leveraged in future emergencies that limit accessibility to traditional schooling, but care is needed to ensure alternative arrangements are accessible and inclusive.61

Counter stigma. Barriers may also be linked to negative social attitudes and stigma against people with disabilities. This may vary by context, but often people with intellectual impairments are particularly stigmatised. Deliberate action is needed to overcome these barriers in disaster planning.61 One approach is to ensure that information for the general public avoids negative or harmful stereotyping messages and images of people with disabilities.

Empower people with disabilities and support them to develop their capacities

For people with disabilities to participate fully and meaningfully in disaster management, technical skills, knowledge and goodwill are needed for all parties involved.

Enhance knowledge for people with disabilities. People with disabilities have the right to education. Their empowerment can be supported through inclusive general education as well as through opportunities to gain knowledge around what to do in crisis situations.66

Enhance knowledge among policymakers. Improved knowledge of disability among policymakers and those implementing policies can also support a more effective and inclusive response to a crisis.67

Enable economic empowerment. Establish long-term interventions, including skills development, aimed at building the self-reliance of people with disabilities. These interventions can help people with disabilities overcome day-to-day financial insecurity as well as be more resilient in the face of shocks.61

Be accountable to people with disabilities. It is important to build accountability mechanisms into crisis management efforts to ensure that policy, planning and responses led by governments, donors, UN agencies and other actors are disability inclusive.62

Support people and networks who support people with disabilities. Empowering people with disabilities also requires supporting the family members, friends, community networks and organisations that care for them – both during emergencies and in day-to-day life. This care is often gendered, with women most often taking on this role.68

Disaggregate data for monitoring and inclusion

Data disaggregated by disability. Up-to-date and internationally comparable data on people with disabilities must be available. Policymakers and decision-makers should use these data in advance of and during crises to inform Humanitarian Response Plans (HRPs) and the development of rapid interventions that are disability inclusive when disasters strike (Box 4).69

Make sure data are comparable. Utilising a recognised approach can support international comparability of data. Tools such as the Washington Group Short Set of Questions on Disability, promoted by the UN, can help emergency planners and implementers identify people with disabilities.70 In turn, this information helps with planning accessible and inclusive humanitarian initiatives and services, particularly for those most at risk. Training and support are needed to implement the tool effectively.71 Data disaggregated by disability (alongside other standard data disaggregated by sex and age) allow for analysis of how marginalised groups are affected by a crisis and how effectively their needs are addressed by a response.55 Disability-inclusive data are also important for accountability mechanisms for stakeholders to ensure their contributions to a response are disability inclusive.62

Box 4. Identifying disability data and data needs

An Advisory Group of UN agencies led by UNICEF developed a useful decision tree tool to help responders reach their data goals. It begins by encouraging reflection on what data are needed for, then determining whether relevant data already exist, and finally assessing the reliability of the data. In the absence of reliable data, the tool offers a range of data collection options for responders to consider, including both quantitative and qualitative methods.72

Source: Authors’ own unless otherwise stated.

Contextualise data. Disaggregated data on disability must also be taken into account alongside context-specific, qualitative data informed by social science. Together they can help illuminate why and how people with some types of disabilities or backgrounds may be more vulnerable (e.g., if they face more stigma), and thus shed light on how these groups can best be supported.

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by Obindra Chand (HERD International and University of Essex), Katie Moore (Anthrologica) and Stephen Thompson (Institute of Development Studies (IDS)), supported by Tabitha Hrynick (IDS and SSHAP). Input was received from a range of experts, and the brief was reviewed by Megan Shcmidt-Sane (IDS and SSHAP), Jennifer Palmer (LSHTM and SSHAP), Pallav Pant (Atullya Foundation), Maria Kett (UCL) and Raissa Azzalini (Oxfam) and Juliet Bedford (Anthrologica). The brief was edited Harriet MacLehose (SSHAP editorial team).

Contact

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Juliet Bedford ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica, CRCF Senegal, Gulu University, Le Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, University of Ibadan, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

Keep in touch

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Chand, O.; Moore, K. and Thompson, S. (2023) Key Considerations: Disability-Inclusive Humanitarian and Emergency Response in South and Southeast Asia and Beyond. Social Science In Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) DOI: www.doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2023.019

Published July 2023

© Institute of Development Studies 2023

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.

References

- Elisala, N., Turagabeci, A., Mohammadnezhad, M., & Mangum, T. (2020). Exploring persons with disabilities preparedness, perceptions and experiences of disasters in Tuvalu. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0241180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241180

- Hillgrove, T., Blyth, J., Kiefel-Johnson, F., & Pryor, W. (2021). A synthesis of findings from ‘rapid assessments’ of disability and the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for response and disability-inclusive data collection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9701. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189701

- National Federation of Disabled – Nepal (NFDN). (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on persons with disabilities: A rapid assessment report. https://nfdn.org.np/impact-of-covid-19-pandemic-and-lockdown-on-persons-with-disabilities-a-rapid-assessment-report

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). (2022). Background paper for regional consultation on facilitating innovative action on disability-inclusive and gender-responsive DRR: Review of disability-inclusive and gender-responsive disaster risk reduction in Asia and the Pacific. UNESCAP. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/Background%20paper_ESCAP%20Regional%20Consulation%20on%20DiDRR%2020220428%20final.pdf

- Aryankhesal, A., Pakjouei, S., & Kamali, M. (2018). Safety needs of people with disabilities during earthquakes. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 12(5), 615–621. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2017.121

- Fefoame, G. O. (2023). Disability should not be a death sentence: Global disaster response must be inclusive. BMJ, 381, p1440. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p1440

- WHO. (2023, March). Disability. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). (2022, October). High-level intergovernmental meeting on the final review of the Asian and Pacific decade of persons with disabilities, 2013-2022. https://www.unescap.org/events/2022/high-level-intergovernmental-meeting-final-review-asian-and-pacific-decade-persons

- Chaney, P. (2017). Comparative analysis of civil society and state discourse on disabled people’s rights and welfare in Southeast Asia 2010–16. Asian Studies Review, 41(3), 405–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2017.1336612

- Kc, H. (2016). Disability discourse in South Asia and global disability governance. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 5(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v5i4.314

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). (2018). Incheon strategy to ‘Make the Right Real’ for persons with disabilities in Asia and the Pacific and Beijing declaration including the action plan to accelerate the implementation of the Incheon strategy. https://www.unescap.org/resources/incheon-strategy-make-right-real-persons-disabilities-asia-and-pacific-and-beijing

- Dhaka Declaration 2015+1; Adopted at the Dhaka Conference 2018 on disability and disaster risk management Dhaka, Bangladesh, May 15-17, 2018. (2018). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). https://www.preventionweb.net/files/58486_dhakadeclaration2015ondisabilityand.pdf

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). (2015). Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030

- DFID – UK Department for International Development. (2019). Guidance on strengthening disability inclusion in Humanitarian Response Plans. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/guidance-strengthening-disability-inclusion-humanitarian-response-plans

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.). Disability-inclusive humanitarian action. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/issues/whs.html

- Humanitarian Exchange. (2020). Disability inclusion in humanitarian action (Issue 78). https://odihpn.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/HE-78_disability_WEB_final.pdf

- Holden, J., Lee, H., Martineau-Searle, L., & Kett, M. (2019). Disability inclusive approaches to humanitarian programming: Summary of available evidence on barriers and what works (Disability Inclusion Helpdesk Research Report No. 9). Disability Inclusion Helpdesk. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/833579/query-9-evidence-humanitarian-response1.pdf

- Bunbury, S. (2019). Unconscious bias and the medical model: How the social model may hold the key to transformative thinking about disability discrimination. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 19(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229118820742

- Waddell, G., Burton, A. K., & Aylward, M. (2008). A biopsychosocial model of sickness and disability. Guides Newsletter, 13(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/amaguidesnewsletters.2008.MayJun01

- Devkota, H. R., Clarke, A., Murray, E., Kett, M., & Groce, N. (2021). Disability, caste, and intersectionality: Does co-existence of disability and caste compound marginalization for women seeking maternal healthcare in southern Nepal? Disabilities, 1(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1030017

- Age and Disability Capacity Programme (ADCAP). (2018). Humanitarian inclusion standards for older people and people with disabilities. https://www.helpage.org/silo/files/humanitarian-inclusion-standards-for-older-people-and-people-with-disabilities.pdf

- Banks, L. M., Kuper, H., & Polack, S. (2017). Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0189996. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189996

- Hossain, M., Pearson, R., McAlpine, A., Bacchus, L., Muuo, S. W., Muthuri, S. K., Spangaro, J., Kuper, H., Franchi, G., Pla Cordero, R., Cornish-Spencer, S., Hess, T., Bangha, M., & Izugbara, C. (2020). Disability, violence, and mental health among Somali refugee women in a humanitarian setting. Global Mental Health, 7, e30. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2020.23

- Human Rights Watch. (2021, June 8). Persons with disabilities in the context of armed conflict: Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/08/persons-disabilities-context-armed-conflict

- Berghs, M. (2012). War and embodied memory: Becoming disabled in Sierra Leone (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315547749

- New Era. (2001). A situation analysis of disability in Nepal: Executive summary of disability sample survey. https://rcrdnepa.files.wordpress.com/2008/05/a-situation-analysis-of-disability-in-nepal-2001.pdf

- Eide, A. H., Neupane, S., & Hem, K.-G. (2016). Living conditions among people with disability in Nepal. https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/sintef-teknologi-og-samfunn/rapporter-sintef-ts/sintef-a27656-nepalwebversion.pdf

- Atullya Foundation. (2021). Disability inclusive get ready guidebook. https://atullya.com.np/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Disability-Inclusive-Get-Ready-Guidebook-English-1.pdf

- Lord, A., Sijapati, B., Baniya, J., Chand, O., & Ghale, T. (2016). Disaster, disability and difference: A study of the challenges faced by persons with disabilities in post-earthquake Nepal. Social Science Baha and United Nations Development Programme in Nepal. https://www.undp.org/nepal/publications/disaster-disability-and-difference

- Lamichhane, K. (2015). Social inclusion of people with disabilities: A case from Nepal’s decade-long civil war. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2013.861866

- Adhikari, D. (2019, July 13). Nepal: 13 years after civil war ends, victims await justice. Anatolia Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/nepal-13-years-after-civil-war-ends-victims-await-justice/1530499

- Devkota, B., & van Teijlingen, E. R. (2010). Understanding effects of armed conflict on health outcomes: The case of Nepal. Conflict and Health, 4(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-4-20

- Sisk, T. D., & Bogati, S. (2015, June 2). Natural disaster & peacebuilding in post-war Nepal: Can recovery further reconciliation? Political Violence at a Glance. https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2015/06/02/natural-disaster-peacebuilding-in-post-war-nepal-can-recovery-further-reconciliation/

- Pfefferle, A. (2015, September 25). Nepal: Paving the way for reconstruction. ACLED. https://acleddata.com/2015/09/25/nepal-paving-the-way-for-reconstruction/

- Rohwerder, B. (2020). Disability inclusive development—Nepal situational analysis. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/15510

- Constitution of Nepal 2015 [unofficial translation], (2015). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/MONOGRAPH/100061/119815/F-1676948026/NPL100061%20Eng.pdf

- Consortium “United Nations workstream on COVID-19 disability inclusive health response and recovery”, Cieza, A., Kamenov, K., Al Ghaib, O. A., Aresu, A., Chatterji, S., Chavez, F., Clyne, J., Drew, N., Funk, M., Guzman, A., Guzzi, E., Khasnabis, C., Mikkelsen, B., Minghui, R., Mitra, G., Narahari, P., Nauk, G., Priddy, A., … Widmer-Iliescu, R. (2021). Disability and COVID-19: Ensuring no one is left behind. Archives of Public Health, 79(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00656-7

- Central Bureau of Statistics, & United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2014). Population Monograph of Nepal 2014 Volume II: Social Demography. Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Secretariat. https://nepal.unfpa.org/en/publications/population-monograph-nepal-2014-volume-ii-social-demography

- Chand, O. (2020, June 8). Pain and plight of people with disabilities during COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections from Nepal. Medical Anthropology at UCL. https://medanthucl.com/2020/06/08/pain-and-plight-of-people-with-disabilities-during-covid-19-pandemic-reflections-from-nepal/

- The Act Relating to Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Pub. L. No. 2074 (2017). https://www.lawcommission.gov.np/en/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-Act-Relating-to-Rights-of-Persons-with-Disabilities-2074-2017.pdf

- Banskota, M. (n.d.). Nepal disability policy review. Disability Research Center, School of Arts, Kathmandu University. https://drc.edu.np/storage/publications/Kele3p6ZwOcvDK2D885O7Rz04F9z2OraQrJgmozx.pdf

- Protection and Welfare of the Disabled Persons Act, Pub. L. No. 2039 (1982). https://lawcommission.gov.np/en/?cat=596

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol, (2007). https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

- National Federation of Disabled – Nepal (NFDN). (2013). Accessible Physical Structure and Communication Service Directive for People with Disabilities 2013. https://nfdn.org.np/national-policies/accessibility-guideline-eng/

- Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act, Pub. L. No. 2074 (2017). https://bipad.gov.np/uploads/publication_pdf/DRRM_Act_and_Regulation_english.pdf

- Humanitarian Disability Charter. (2023). Charter on inclusion of persons with disabilities in humanitarian action. http://humanitariandisabilitycharter.org/

- Ministry of Health and Population, & Government of Nepal. (2020). Health sector emergency response plan: COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/health-sector-emergency-response-plan-covid-19-endorsed-may-2020.pdf

- Ministry of Health and Population. (2019). National guidelines for disability inclusive health services, 2019. Government of Nepal. https://www.nhssp.org.np/Resources/GESI/National_Guidelines_Disability_Inclusive_Health_Services2019.pdf

- Banks, L. M., Walsham, M., Neupane, S., Neupane, S., Pradhananga, Y., Mahesh Maharjan, Blanchet, K., & Kuper, H. (2018). Disability-inclusive social protection research in Nepal: A national overview with a case study from Tanahun district. International Centre for Evidence in Disability Research Report: London, UK. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/Full-report_Nepal.pdf

- Blanchet, K., Girois, S., Urseau, I., Smerdon, C., Drouet, Y., & Jama, A. (2014). Physical rehabilitation in post-conflict settings: Analysis of public policy and stakeholder networks. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(18), 1494–1501. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.790489

- National Federation of the Disabled, Nepal (NFDN). (n.d.). A general guidelines for persons with disabilities and all stakeholders on disability inclusive response against COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved 30 May 2023, from https://nfdn.org.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NFDN-General-Guidelines-on-COVID-19-response-PDF.pdf

- HERD International, & Karuna Foundation. (2021). Breaking barriers: Ensuring sexual and reproductive health rights of persons with disabilities: Proceeding report, December, 2021. https://www.herdint.com/resources/breaking-barriers-ensuring-sexual-and-reproductive-health-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/

- National Federation of the Disabled – Nepal (NFDN), & Kathmandu Metropolitan City. (2018). Report on accessibility audit on Kathmandu Nepal. https://nfdn.org.np/publications/access-audit-report/

- World Humanitarian Summit secretariat. (2015). Restoring humanity global voices calling for action: Synthesis of the consultation process for the World Humanitarian Summit. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/restoring-humanity-global-voices-calling-action-synthesis-consultation-process-world

- UN OCHA (United Nation’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). (2020). Global humanitarian response plan COVID-19 (April – December 2020). https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-response-plan-covid-19-april-december-2020

- Djalante, R., Shaw, R., & DeWit, A. (2020). Building resilience against biological hazards and pandemics: COVID-19 and its implications for the Sendai Framework. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, 100080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100080

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). (2019). IASC Guidelines, Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action, 2019 | IASC. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-guidelines-on-inclusion-of-persons-with-disabilities-in-humanitarian-action-2019

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). (2019). Executive Summary: IASC Guidelines on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities inHumanitarian Action. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2022-10/Executive%20Summary%20-%20IASC%20Guideline%20on%20Inclusion%20of%20Persons%20with%20Disability%202019.pdf

- Mzini, L. B. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic planning and preparedness for institutions serving people living with disabilities in South Africa: An opportunity for continued service and food security. Journal of Intellectual Disability Diagnosis and Treatment, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.6000/2292-2598.2021.09.01.2

- Handicap International. (2020). COVID-19 in humanitarian contexts: No excuses to leave persons with disabilities behind! Evidence from HI’s operations in humanitarian settings. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/covid-19-humanitarian-contexts-no-excuses-leave-persons-disabilities-behind-evidence

- Wickenden, M., Thompson, S., Rohwerder, B., & Shaw, J. (2022). Taking a disability-inclusive approach to pandemic responses, IDS Policy Briefing 175. Institute of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.19088/IDS.2021.027

- UN (United Nations). (2020). Policy brief: A disability-inclusive response to COVID-19. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wpcontent/uploads/sites/15/2020/05/sg_policy_brief_on_persons_with_disabilities_final.pdf

- UNESCO. (n.d.). World atlas of languages. Retrieved 30 May 2023, from https://en.wal.unesco.org/

- Ghimire, M. (2019, December 13). Treading with technology. National Federation of the Disabled – Nepal. https://nfdn.org.np/rupantaran/2073-02/trading-with-technology

- Paul, J. D., Bee, E., & Budimir, M. (2021). Mobile phone technologies for disaster risk reduction. Climate Risk Management, 32, 100296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100296

- Atuallya Foundation (Director). (2021, October 12). Disability inclusive simulation exercise on fire safety and earthquake program. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qejJ9WGyPg

- Rahmat, H., & Pernanda, S. (2021). The importance of disaster risk reduction through the participation of person with disabilities in Indonesia. Proceeding Iain Batusangkar, 1(1). https://ojs.iainbatusangkar.ac.id/ojs/index.php/proceedings/article/view/2915

- Kim, A., & Woo, K. (2022). Gender differences in the relationship between informal caregiving and subjective health: The mediating role of health promoting behaviors. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 311. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12612-3

- NU CEPAL. (2021). Persons with disabilities and their rights in the COVID-19 pandemic: Leaving no one behind. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/46603

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. (n.d.). Washington Group Set on Functioning. Retrieved 18 May 2023, from https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-short-set-on-functioning-wg-ss/

- Sloman, A., & Margaretha, M. (2018). The Washington Group Short Set of Questions on Disability in disaster risk reduction and humanitarian action: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 995–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.08.011

- International Organization for Migration (IOM) – Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM). (n.d.). Collection of data on disability inclusion in humanitarian action: Decision tree. https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/tools/Interagency%20Decision%20Making%20Tree%20on%20Data%20for%20Disability%20Inclusion.pdf