This brief distils best data practice recommendations through consideration of key issues involved in the use of technology for surveillance, fact-checking and coordinated control during crisis or emergency response in resource constrained urban contexts. We draw lessons from how data enabled technologies were used in urban COVID-19 response, as well as how standard implementation procedures were affected by the pandemic. Disease control is a long-standing consideration in building smart city architecture, while humanitarian actions are increasingly digitised. However, there are competing city visions being employed in COVID-19 response. This is symptomatic of a broader range of tech-based responses in other humanitarian contexts. These visions range from aspirations for technology driven, centralised and surveillance oriented urban regimes, to ‘frugal innovations’ by firms, consumers and city governments. Data ecosystems are not immune from gendered- and socio-political discrimination, and technology-based interventions can worsen existing inequalities, particularly in emergencies. Technology driven public health (PH) interventions thus raise concerns about 1) what types of technologies are appropriate, 2) whether they produce inclusive outcomes for economically and socially disadvantaged urban residents and 3) the balance between surveillance and control on one hand, and privacy and citizen autonomy on the other.

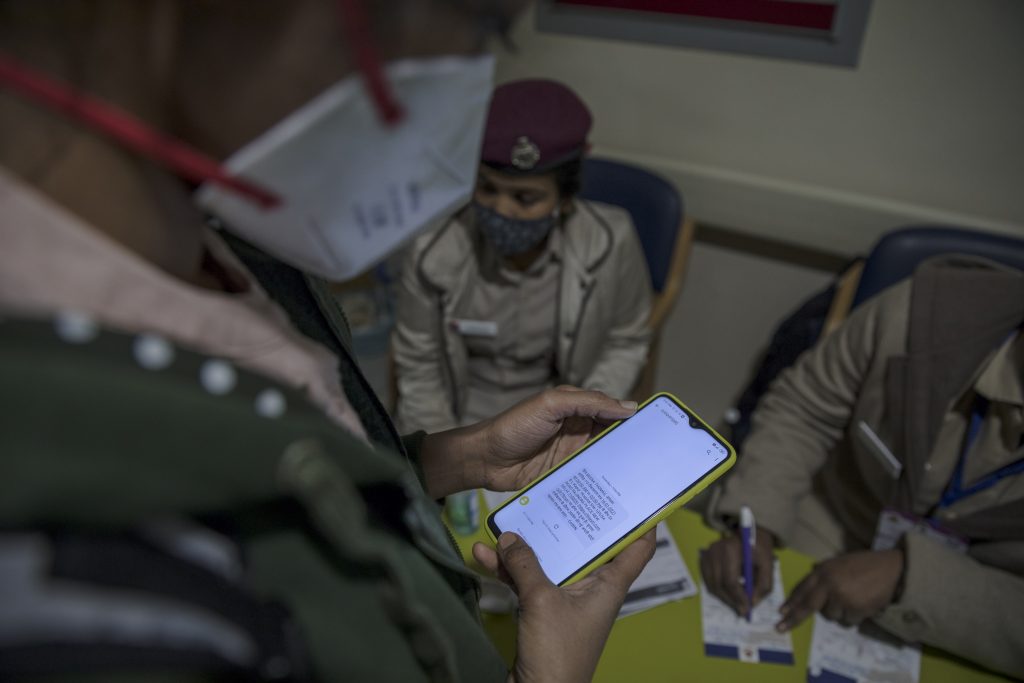

Our findings and recommendations derive from a multi-year research collaboration with municipal authorities across several cities engaged in the Government of India’s Smart Cities Mission. This included dialogue with relevant city- and national- authorities in the months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and once the national decision to lockdown all public interaction was taken, as well as critical reflection with key city-stakeholders six months after control interventions were first implemented. This brief is intended for urban local authorities mandated with pandemic response, and for community groups representing those who bear the triple burden of disease, income vulnerability, and of marginalisation in official data architectures. It will also be of interest to local and national authorities and community groups utilising smart urban technologies in other humanitarian contexts, as well as other PH stakeholders engaging in contexts where data infrastructures are thwarted by information and communication gaps.