INTRODUCTION

Refugees from Ukraine are entitled to free access to all health services in neighbouring countries, including routine vaccination services for children. All Ukrainian children in Poland for more than three months are expected to be vaccinated, and have proof of vaccination, either according to the Ukrainian national schedule or the Polish national schedule. During the initial phase of the emergency response, there have been concerns about low vaccination rates among refugees who are on the move.

This brief is intended for local government actors, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and international agencies in Poland who are supporting refugees. It summarises existing information about the factors influencing vaccination-related practices during this emergency phase. It also presents strategic and practical considerations to inform the design of interventions to create demand for routine immunisation among Ukrainian refugees. The brief begins with a historical overview of routine vaccination in Ukraine. Next, it explores how this shaped the vaccination of Ukrainians in Poland before the current conflict (from February 2022) and the attitude of Ukrainian refugees to receiving vaccination in Poland. Finally, it draws on ongoing research that highlights how refugees’ uncertain longer-term plans limit their vaccination uptake.

This brief was requested by UNICEF Emergency Response Team (Geneva) and was written by Erica Richardson (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine), reviewed by Olivia Tulloch (Anthrologica), Marina Braga, Tetiana Stepurko (National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy), Mariana Palavra (UNICEF), and Sanja Matovic (Euro Health Group). This brief was edited by Victoria Haldane (Anthrologica). This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

- Routine vaccination coverage for Ukrainian children is below World Health Organization (WHO) recommended levels. Routine vaccination is mandatory in Poland and a vaccination certificate is required for a child to attend school. Ensuring good access to vaccination services in Poland for child refugees from Ukraine, and providing tailored health promotion activities for caregivers, is a public health priority.

- Caregivers are unsure when their return to Ukraine will be possible, how long they will stay in Poland, or whether they will move to another country. Messaging around vaccination needs to acknowledge this uncertainty and emphasise the importance of their children receiving routine vaccinations in Poland, highlighting the social benefits vaccination entails.

- Currently, Ukrainian refugees rely on social media and informal networks to access information on vaccination in Poland. Full information about routine vaccines and vaccination programmes needs to be made available through official channels online, including social media platforms, in Ukrainian, but also possibly Russian languages.

- The vaccination catch-up schedule means that in the absence of an official vaccination passport it should be assumed that the child is unvaccinated. The catch-up schedule for Ukrainian refugee children must be clearly explained to caregivers to minimise concerns around vaccination.

- Caregivers will need vaccination certificates that are valid across the European Union (EU) and upon return to Ukraine. Agreements with the Ukrainian Ministry of Health could be sought to reassure caregivers that childhood vaccination schedules are compatible and medical records can be updated upon to return Ukraine.

- It is important to ensure that all groups in Poland have good access to vaccination programmes. For the greatest public health benefits, routine vaccination services should be available to all migrants, refugees and any other Polish residents (legal or otherwise).

- Trust in the Polish health system is high, so Polish providers should lead in all interventions and communications – building on existing resources.

ROUTINE VACCINATION IN UKRAINE

All vaccines included in the National Recommended Immunisation Schedule are procured using state budget funds and provided free of charge in Ukraine. The schedule includes vaccines for the prevention of ten diseases: hepatitis B, tuberculosis, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, poliomyelitis, Haemophilus Influenzae Type b (Hib), measles, rubella, and mumps. Vaccination is recommended, but not mandatory.

Vaccines are administered in primary care, and since 2019 individuals must be registered with a primary care provider to access state-financed healthcare. As of 2018, most people were registered (Stepurko et al. 2019). Primary care services for children, including vaccinations, are provided by either a paediatrician working at the primary care level or a general practitioner (GP)/family doctor.

In practice, the vaccination process varies from one region to another, but most children are first required to have a check-up with their primary care physician to ensure they are well enough to be vaccinated. Liability for any adverse reactions lies with the doctor in charge when it was administered. In response to the risk of criminal prosecution, since 2010 the medical community has sought written consent from caregivers for childhood vaccinations. While not a legal requirement, requesting consent to waive a vaccinator’s legal liability for any side effects frames vaccination as inherently risky rather than inherently safe. Details of a child’s vaccinations are recorded in a Vaccination Passport that stays with the caregiver, and a note is made in the child’s medical records, which are increasingly held digitally. This means most Ukrainian vaccination records can be accessed from anywhere in the world. However, people vaccinated in currently-occupied territories cannot access their records in this way. Routine childhood vaccines are now widely stocked in primary care, but sometimes caregivers prefer to buy vaccines privately as they perceive them to be of higher quality (Twigg 2016). Lack of trust in vaccine quality is a problem that has deep roots in Ukraine (Bazylevych 2011, UNICEF 2016).

Box 1. Ukrainian refugees in Poland

As of May 2022, a third of the Ukrainian population has been displaced by war, and more than 6.8 million refugees have fled Ukraine since the Russian invasion on 24 February 2022. Over 3.6 million have been displaced to Poland (UNHCR 2022a). Nearly all have been women (96%), and most are travelling with children (76%). One in five of these children are aged under five years (UNHCR 2022b).

The number of people crossing the border varies with the intensity and location of the conflict zones. Some refugees who fled early in the invasion have already started returning home (UNHCR 2022a).

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON VACCINATION PROGRAMMES IN UKRAINE

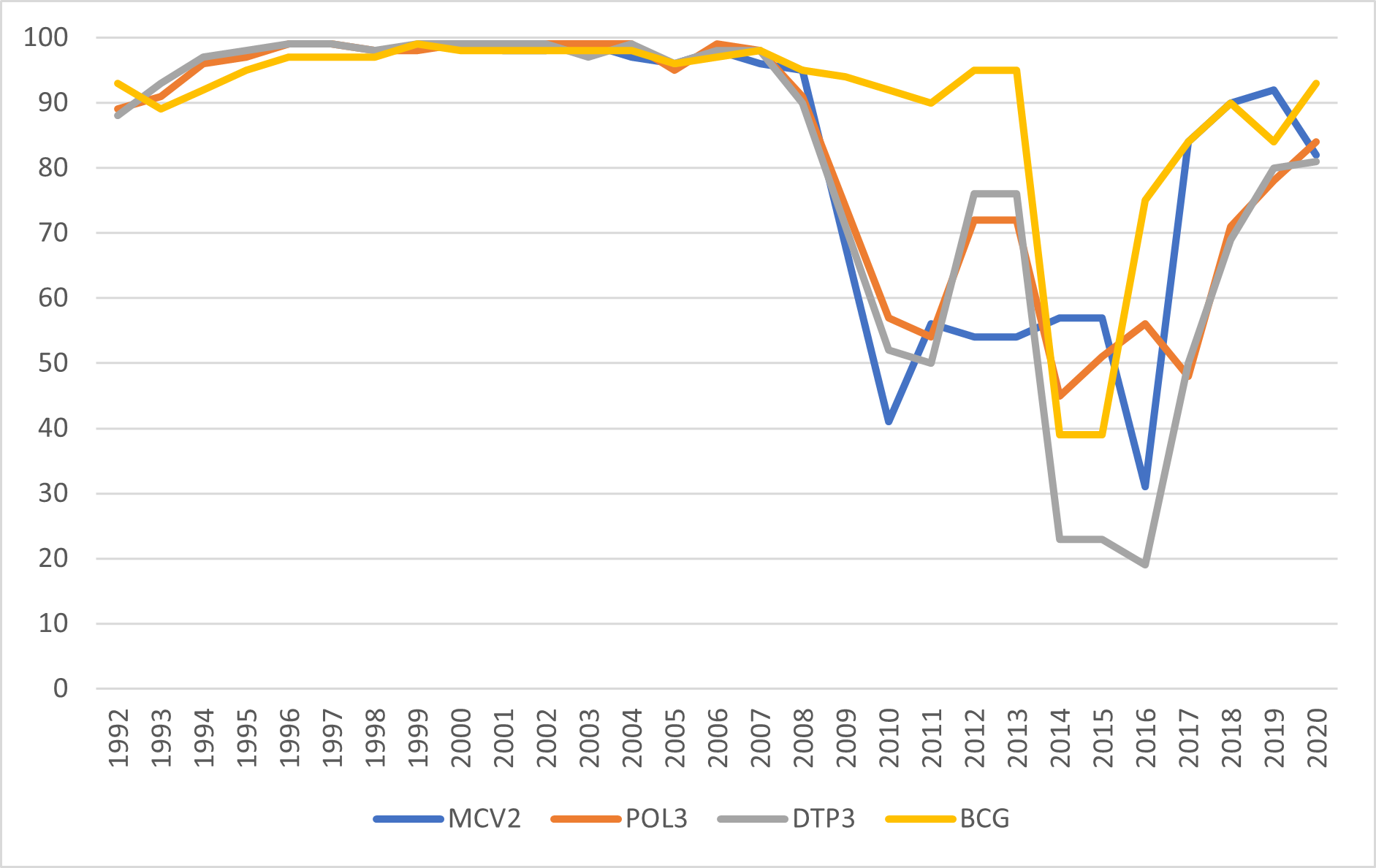

Prior to 1991 Ukraine had a well-developed routine vaccination programme with high coverage rates, but at different times since independence there have been major challenges to maintaining vaccination programmes. Consequently, there have also been outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. From 1991–1997 there was a diphtheria epidemic, despite high vaccination rates, due to ineffective vaccines (Nekrassova et al. 2000). From 2009 there was a sharp decline in coverage for all vaccines, and by 2014-2016, Ukraine had one of the lowest rates of routine vaccinations in Europe. Coverage with three doses of polio vaccine declined to 39% in 2014, while coverage with both doses of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine fell from 95% in 2008 to 31% in 2016 (Fig. 1). Chronic under-vaccination resulted in the accumulation of a large number of children susceptible to polioviruses (estimated by WHO at 1.5–1.8 million in 2014), as well as to measles, rubella, and diphtheria (Khetsuriani et al. 2017). A polio outbreak was confirmed on 28 August 2015, and outbreaks of measles were confirmed in 2012 and 2016–2019 (UNICEF 2016).

Data source: UNICEF/WHO estimates https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/immunization/

By 2019, vaccination coverage was 93% for the first MMR vaccination at 12 months and 92% for the second MMR vaccination at six years of age (Fig. 1). While coverage rates were still below the WHO-recommended national target of 95%, they had improved substantially since 2016 (see Fig. 1). Vaccination rates were 80% for three doses of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine, and 80% for two doses of polio vaccine (reaching 84% in 2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic affected access to routine vaccination services and rates fell. For example, as of June 2020, only 28% of one-year-old children received the first dose of MMR vaccine. Moreover, in August 2021, only 53% of children under the age of one had received their polio vaccines. In October 2021, poliovirus was detected in an unvaccinated 18-month-old child in the Rivne region, in western Ukraine, and a polio vaccination catch-up campaign was launched on 1 February 2022 (Ericksen et al. 2021).

While improvements in vaccination coverage before 2020 are the result of concerted, ongoing, multiagency efforts, many factors contributed to the dramatic decline in immunisation coverage in 2009 including:

- Vaccine procurement problems

- Hostile anti-vaccine media environment

- Widespread mistrust in vaccines among the general population

- Concerns among healthcare workers

Together these factors offer insights on the underlying causes of low vaccination coverage in Ukraine and have implications for efforts to promote immunisation in refugee populations.

Vaccine procurement problems

For many years routine vaccination in Ukraine was a neglected issue, and since 2011 vaccine procurement has had no dedicated budget line in the national health budget. Without budgetary prioritisation, there were funding shortfalls, resulting in lower vaccine procurement and administration. The budgetary cycle also acted as a barrier to effective procurement. Multi-year tenders were not allowed, although these are preferred by manufacturers. Further, due to delays in budget finalisation, procurement had to happen quickly and late in the year when available stock might be low.

By 2013, the state budget covered only about 65% of the country’s vaccination needs, and by mid-2014 there were no routine vaccinations available across Ukraine (Twigg 2016). Corrupt practices also saw vaccines procured at an artificially inflated price through shell companies, thus ensuring large (illegal) profits for the owners of these companies (Twigg 2016).

From 2016–2019, UNICEF conducted vaccine procurement for Ukraine. This helped support the supply of high-quality vaccines at a reduced cost, as well as ensure transparent procurement processes.

Hostile media environment

Powerful and politically-connected business lobby groups benefited from a labyrinthine public procurement system and restrictions on international procurement. They therefore sought to maintain the status quo, and in so doing they undermined trust in vaccines (UNICEF 2016). Business lobby groups who ran the shell companies profiting from corrupt public procurement were also often major shareholders in media groups. They were also at the forefront of paying for anti-vaccine misinformation to be pushed online (Twigg 2016). Those pushing these dangerous narratives sought to sow mistrust of affordable vaccines procured through international partners, but the impact undermined trust in vaccines more broadly. From 2008, when a media panic about vaccines began in Ukraine (see Box 2), UNICEF has been trying to restore public trust in vaccination, including through education, changing behaviour, and activities to build capacity (UNICEF 2016). Proactively working to combat misinformation online has been a large part of these efforts.

Box 2. The media panic that undermined vaccination and led to a polio outbreak in Ukraine

High levels of vaccine hesitancy around the time of the polio outbreak in 2015 can be directly linked to a media panic over vaccinations in 2008 during a national measles-rubella vaccination campaign (UNICEF 2016).

In May 2008, a recently vaccinated 17-year-old died from bacterial meningitis, but the death was wrongly attributed to the vaccine. Media coverage of the event, and subsequent contradictory government statements, sowed distrust among caregivers and health care workers.

Over 100 people, mostly children, were admitted to hospital with various ailments that were wrongly attributed to the vaccinations. Irresponsible reporting about these events on television, newspaper, and social media provided fertile ground for conspiracies against a background of high levels of corruption in the health system (Twigg 2016).

The resonance of this story should not be underestimated – it was cited by Ukrainian caregivers living in Poland in research conducted a decade later (Ganczak et al. 2021).

Widespread mistrust in vaccinations among the general population

A survey commissioned by UNICEF and conducted in September 2021 found that most Ukrainians (82%) support vaccinating children against vaccine-preventable diseases. Of respondents with children aged under 6 years, 81% had vaccinated according to the vaccination schedule, 15.8% had postponed vaccination, and 2.4% had refused vaccination. Of those who postponed vaccination, the most common reason given was “I’m waiting for the child to grow up to make it easier to monitor reactions to vaccines” (Euro Health Group and UNICEF ECARO 2022). Most respondents trusted their primary care physician as the most reliable source of information on vaccinations, followed by the Ministry of Health and the Public Health Centre. Respondents who got their information online from social networks, Viber, Telegram, and English-language resources were less likely to vaccinate their children (Euro Health Group and UNICEF ECARO 2022).

Attitudes vary by region, with significantly higher levels of vaccine hesitancy in western Ukraine than in eastern and southern Ukraine (Stepurko et al. 2019). The same survey found that the most common reasons for not vaccinating were illness in the child (46% of respondents with children under 18 years), fear of complications or negative reactions (41%), or lack of trust in vaccine manufacturers (31%).

The lack of trust in vaccines is inextricably linked to corruption in both Ukrainian society and the health system. Historically, informal practices in the health system have included informal payments and personal connections to enable patient choice or access to goods or services in short supply (Stepurko et al 2013, Bazylevych 2009). However, informal practices also extend to reports of doctors issuing fake immunisation certificates so unvaccinated children can enrol in education (Ganczak et al 2021; Khalets’ka & Sereda 2018), and falsifying records to personalise the national immunisation schedule by spacing out vaccinations (Bazylevych 2011).

The prevalence of informal practices, in particular informal payments, undermines trust in the health system as a whole, including trust in vaccine safety, physician training, and health care quality. Vaccine confidence requires trust in those who make decisions about vaccine provision (the policymaker), trust in the vaccinator or other health professional (the provider), and trust in the vaccine (the product) (de Figueiredo et al. 2020). Particularly before 2014, a breakdown of trust in authorities led to vaccine refusal (Twigg 2016). Since 2014, despite challenges, significant progress has been made in tackling corruption in Ukraine, particularly in public procurement mechanisms (Kaleniuk & Halushka 2021). In doing so, accountability and transparency in vaccine procurement have been strengthened.

Concerns among healthcare workers

Alongside the issue of liability highlighted above, health care workers administering vaccines have been expected to follow complex, and often contradictory, official guidelines. This complexity has resulted in health care workers’ sometimes considering seasonal coughs and colds as sufficient reason to defer vaccination. These guidelines have now been simplified, but temporary contraindications may have contributed as much as 5-10% towards the previous decline in vaccination coverage rates (Twigg 2016).

Other procedural issues frame vaccination as unnecessarily risky, and disincentivise doctors from vaccinating children. For example, if a child dies within 30 days of vaccination, the vaccination is listed as the cause of death until an investigation into the cause of death is completed. While this investigation is ongoing, the health care worker who administered the vaccination can be suspended (UNICEF 2016, Twigg 2016).

Vaccination programmes since 24 February 2022

Vaccination activities have continued irregularly since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, but these activities vary significantly by region. The polio catch-up vaccination campaign that started on 1 February 2022 reached over 8,000 children between 16 March and 4 April 2022, but data since 24 February 2022 are unreliable. For example, reports of more than 100% coverage in certain areas require further verification. Some regions (Donesk, Luhansk, Kherson, Mariupol, Kharkiv, Zaporizhya, Chernihiv, Sumy and Kyiv) are conflict zones or under Russian occupation, which has caused major disruption to vaccination programmes. Internal displacement from these regions has also complicated the situation elsewhere in the country. Strategies for routine vaccination service delivery need to be adapted. For example, mobile vaccination teams and offering vaccination at crossing points are strategies under consideration (GEPI 2022).

VACCINATION FOR UKRAINIANS IN POLAND

In Poland, the routine vaccination programme is the responsibility of primary care providers (see Kowalska-Bobko & Badora-Musiał 2018). Under the law on the prevention and control of infections and communicable diseases in humans (OJ L 2008 No. 234 item 1570) vaccinators (usually general practitioners) must:

- Maintain medical records concerning mandatory vaccination, including keeping immunisation cards and recording the completion of vaccination schedules.

- Report the mandatory vaccinations carried out and the vaccination status of their registered patients to the State Country Sanitary Inspector.

Immunisation cards are issued at birth in Poland and are held at the GPs office, mostly in digital form.

Even before the Russian invasion in February 2022, there were around 1.25 million Ukrainian migrants living and working in Poland. These were typical economic migrants – working-age adults seeking better employment opportunities (Ganczak et al. 2021). Ukrainian migrants were already recognised as being an under-vaccinated group. Qualitative research has explored the beliefs, attitudes, and practices behind this, as well as highlighting important pre-existing barriers to access (Ganczak et al. 2021).

Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour

Following measles outbreaks in Poland in 2019, there was a push to increase the vaccination coverage of Ukrainian migrants. Health promotion materials in Polish, Ukrainian, and English languages were circulated widely; however, posters and pamphlets were not the main source of information for Ukrainian migrants. Ukrainian migrants relied instead on internet searches and Facebook to get the information they needed about vaccination in Poland (Ganczak et al. 2021).

“Information about vaccines should be provided through the Internet, because everyone is on Facebook. Some advertisements need to be there.” (Ganczak et al 2021)

Barriers to access

Before February 2022, language was the main barrier to routine vaccination. Registering with a GP and getting routine vaccinations for children free of charge was seen by respondents as a relatively straightforward process. However, speaking Polish was seen as crucial to accessing care (Ganczak et al. 2021). The caregivers also reported needing detailed information about the vaccines on offer, where they were manufactured, and potential side effects, but such information is generally only available in Polish.

Nevertheless, when a child had already received some vaccinations in Ukraine and the caregiver had the vaccination passport, a formal translation was not strictly necessary, given that the vaccination schedules in both Ukraine and Poland are compatible and based on international best practice.

“A GP asked about my child’s vaccination record. She did not understand what was written there, so she asked a senior doctor. They figured out that my child had been vaccinated correctly.” (Ganczak et al. 2021)

These insights are important for understanding the barriers to routine vaccination for Ukrainian refugees who are less likely to have a strong command of Polish and potentially see less need to register with a GP when they perceive their stay in Poland to be temporary.

ATTITUDES, INFORMATION SOURCES, AND PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR VACCINATIONS AMONG REFUGEES

Attitudes towards vaccination in Poland

UNICEF has conducted a series of surveys among Ukrainian refugees to understand their attitudes towards vaccinating their children in Poland (UNICEF, forthcoming). The findings describe very important differences between Ukrainian refugees who aim to return to Ukraine and those who do not plan to return.

Most Ukrainian refugees in Poland want to return home once it is safe to do so (88% overall). The main reason why respondents are not ready to get the necessary vaccinations is their plans to leave Poland soon (52%), rather than the lack of information about the vaccination process in Poland (15%). Similarly, Ukrainian refugees arranging to leave Poland to stay in another country report that these plans shape their intentions to seek routine vaccinations for their children. Therefore, when designing interventions and messaging, it is important to consider how future plans influence attitudes towards routine vaccination. Caregivers need to believe vaccination is something worth doing, even if they see their future elsewhere, or their stay in Poland as temporary. Messaging therefore needs to emphasise the importance of vaccinating children sooner rather than later. Given widespread damage to health care infrastructure in Ukraine, even if refugees return home shortly, it will be challenging to keep routine vaccination schedules. Messaging should be clear that receiving routine vaccinations in Poland to protect children while waiting is still the best choice.

Box 3. Guidelines for vaccinating refugees in Poland

Routine childhood vaccination is obligatory in Poland, and this applies to everyone who stays in the country for more than three months. People staying for longer need to be vaccinated in Poland or be able to prove their vaccination status. In the absence of a vaccination passport, children are treated as unvaccinated and the catch-up schedule is followed.

Routine serological testing to determine the status of immunisation is not used, other than for hospitalised children with unknown vaccination status.

For non-citizens legally resident in Poland and registered with a general practitioner, regardless of health insurance cover, vaccines provided as part of the immunisation programme are free of charge up to the age of 19. This is financed from the National Health Fund.

Guidelines for the immunisation of refugee children from Ukraine have been issued by the Polish Ministry of Health. These guidelines prioritise routine childhood vaccinations according to the schedule (particularly MMR, DTP, polio, HepB) plus COVID-19 (Ministry of Health 2022).

For those who want to stay in Poland and find employment, registering with a GP, navigating the health system, and registering their child in school becomes more important (see Box 3). Obtaining the right paperwork, including the mandatory vaccination certificate to access education, is an urgent priority that might encourage vaccination uptake. For example, the surveys show 21% of caregivers consider this a motivation to vaccinate.

Refugees’ trust in Polish health services is quite high (80%), and in 2022 only 6% of respondents reported being hesitant about vaccination. The key barriers to vaccinating children under 6 years identified in this survey were that war interrupted vaccination schedules, and that caregivers intend to return home soon. Respondents reported the main motivation to vaccinate is the understanding that the disease is risker than the vaccination. There is scope to use these ‘push factors’ to motivate caregivers to seek vaccinations in Poland.

The use of the catch-up schedule for Ukrainian refugee children needs to be very clearly communicated to caregivers. The catch-up schedule means that in the absence of the official vaccination passport, it should be assumed that the child is unvaccinated. Messaging about this schedule must minimise concerns about the safety of what might be understood as ‘re-vaccination’. There are reports that parents have asked for antibody testing in order to avoid double vaccination. Therefore, efforts should be made to clarify that antibody testing is not routinely used in Poland unless a child is admitted to hospital. It must be clearly communicated that caregivers will be asked to revaccinate their children (see Box 3). Given the recent history of widespread vaccine hesitancy in Ukraine, it is important that trust in the Polish health system be maintained through clear communication.

Sources of information on vaccination

Currently, Ukrainian refugees rely on social media and informal networks to access information on vaccination in Poland. Full information about the vaccines being administered, any possible side effects, and arrangements for catch-up vaccination programmes need to be made available online. Misinformation about vaccines is rampant in online forums, so this information should be offered through official channels, including social media platforms. Doing so can reduce caregivers’ reliance on informal networks to get vaccination-related information.

While Ukrainian is the official language and it is the main language spoken in Ukraine, Russian is spoken by a substantial part of the population as their first language, especially in southern and eastern Ukraine. Therefore, to ensure accessibility, information should be made available in Ukrainian, but possibly also in Russian. The UNICEF surveys of Ukrainian refugees in Poland found that very few spoke Polish confidently (UNICEF forthcoming). Ukrainian refugees may need interpreting services to access primary care services – including vaccination.

Practical considerations

For vaccination approaches to be effective, there must be processes in place to transfer vaccination-related information and ensure it is recognised upon return to Ukraine or upon relocation to other countries. According to caregivers who arrived in Poland after 24 February, 86% of refugee children are vaccinated already. Of these, 60% have a physical vaccination passport but have left it in Ukraine. Replacing physical records could be challenging for many. Efforts should be made to facilitate access to digital copies from the Ukrainian eHealth system, as well as ensure compatible digital health records between the Ukrainian, Polish and other EU health systems.

For those who have vaccination passports issued in Ukraine, it is important that people working in health and education facilities in Poland know that official translations of vaccination passports or vaccination status certificates into Polish language are not required. Ukrainian refugees should not be charged to translate their vaccination records.

It is important to ensure that all groups in Poland have good access to vaccination programmes. For the greatest public health benefits, routine vaccination services should be available to all migrants, refugees, and any other Polish residents (legal or otherwise). Therefore, any low-threshold vaccination services made available outside the primary care setting should be available to all who need them, not just Ukrainian refugees.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2019). Delivery of immunisation services for refugees and migrants: Technical guidance. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. (Accessed 2 June 2022).

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2015). WHO–UNHCR–UNICEF joint technical guidance: general principles of vaccination of refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. (Accessed 2 June 2022).

REFERENCES

Bazylevych M. (2009). Who is responsible for our health? Changing concepts of the state and the individual in post-Soviet Ukraine. Anthropology of East Europe Review, 27(1):65-75

Bazylevych M. (2011). Vaccination campaigns in postsocialist Ukraine. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 25(4):436-356. Doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2011.01179.x

Eriksen A, Shuftan N, Litvinova Y (2021), Health Systems in Action: Ukraine, Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/health-systems-in-action-ukraine

Euro Health Group and UNICEF ECARO (2022). Drivers Influencing Immunization-Related Behaviour in Ukraine: Evidence Synthesis (Forthcoming)

Ganczak M., Bielecki K., Drozd-Dąbrowska M., Topczewska K., Biesiada D., Molas-Biesiada A., Paulina Dubiel P., Gorman D. (2021). Vaccination concerns, beliefs and practices among Ukrainian migrants in Poland: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health; 21(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10105-9

Global Polio Eradication Initiative [GEPI] (2022). Situation Report #23: Ukraine cVDPV2 Outbreak; 4 April 2022. https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Final-GPEI-Ukraine-SitRep-23-20220404.pdf

Kaleniuk D. & Halushka O. (2021) Why Ukraine’s fight against corruption scares Russia. Foreign Policy 17 December 2021 foreignpolicy.com/2021/12/17/Ukraine-russia-corruption-putin-democracy-oligarchs/

Khalets’ka A &Sereda S (2018) Фальшиві медвідводи від щеплень і «липові» довідки про вакцинацію: для порушників посилять відповідальність. Radio Svoboda. 21 February 2018 https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/29053251.html [accessed 2 June 2022] (in Ukrainian)

Khetsuriani N, Perehinets I, Nitzan D, Popovic D, Moran T, Allahverdiyeva V, Huseynov S, Gavrilin E, Slobodianyk L, Izhyk O, Sukhodolska A, Hegazi S, Bulavinova K, Platov S, O’Connor P. (2017). Responding to a cVDPV1 outbreak in Ukraine: Implications, challenges and opportunities. Vaccine; 35(36):4769-4776. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.036

Kowalska-Bobko I. & Badora-Musiał K. (2018). Poland. In Rechel B., Richardson E., McKee M., The organization and delivery of vaccination services in the European Union (prepared for the European Commission), World Health Organization: Copenhagen

de Figueiredo A., Simas C., Karafillakis E., Paterson P., Larson H.J., (2020) Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. The Lancet; 396(10255):898-908. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0

Ministry of Health (2022) Wytyczne dot. sposobu realizacji szczepień dzieci z Ukrainy, w związku z konfliktem zbrojnym w tym kraju (Guidelines for the realisation of vaccinating children from Ukraine escaping conflict in that country) 10 March 2022 https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/uzupelnienie-komunikatu-z-dnia-4-marca-2022-r-w-sprawie-realizacji-szczepien-ochronnych-u-dzieci-ktore-przekroczyly-granice-rzeczypospolitej-polskiej-z-ukraina-w-zwiazku-z-konfliktem-zbrojnym-na-terytorium-tego-panstwa-o-wytyczne-dotyczace-sposobu-realizacji-szczepien-u-dzieci-na-podstawie-programu-szczepien-ochronnych-pso-na-2022-rok [accessed 30 May 2022]

Nekrassova LS, Chudnaya LM, Marievski VF, Oksiuk VG, Gladkaya E, Bortnitska I, Mercer DJ, Kreysler JV, Golaz A (2000) Epidemic diphtheria in Ukraine, 1991-1997. Journal of Infectious Diseases; 181 Suppl 1:S35-40. doi: 10.1086/315536.

Stepurko T., Pavlova M., Levenets O., Gryga I., Groot W. (2013). Informal patient payments in maternity hospitals in Kiev, Ukraine. International Journal of Health Planning and Management; 28(2):e169-e187. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2155

Stepurko TG, Semygina TV, Barska YuG, Zahozha V, Kharchenko N (2018). Health Index Ukraine – 2018: Results of the National Survey, Kyiv: International Renaissance Foundation. http://ekmair.ukma.edu.ua/handle/123456789/18334

Twigg J., (2016). Polio in Ukraine: Crisis, Challenge, and Opportunity, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS): Washington DC, USA

UNICEF (2016) Polio Outbreak in Ukraine, 2015-2016: Unique Challenges, Comprehensive Response, UNICEF Ukraine Country Office / UNICEF CEE/CIS Regional Office on behalf of GPEI partners in Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine. https://s3.amazonaws.com/gpei-tk/reference_links/en/Polio_Outbreak_Ukraine_Report_FIN_Jan_2017.pdf

UNICEF (forthcoming), Survey of Ukrainian refugees in Poland: Vaccination of preschool children, April 2022

UNICEF Poland Country Office (forthcoming), Research results for the UNICEF/Common Thread Human Centered Design Refugees project.

UNHCR (2022a) Ukraine Situation Flash Update #14, 25 May 2022. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/93039

UNHCR (2022b) Refugee Arrivals from Ukraine into Poland, 25 May 2022. https://reliefweb.int/report/poland/refugee-arrivals-ukraine-poland-update-25052022

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This brief has been written by Erica Richardson ([email protected]). It was reviewed externally by Marina Braga, Mariana Palavra (UNICEF) and Sanja Matovic (Euro Health Group). The briefing was internally reviewed by Olivia Tulloch (Anthrologica) and edited by Victoria Haldane and Leslie Jones (Anthrologica). This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

CONTACT

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Olivia Tulloch ([email protected]). Key Platform liaison points include: UNICEF ([email protected]); IFRC ([email protected]); and GOARN Research Social Science Group ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and Wellcome Grant Number 219169/Z/19/Z and the Smart Data For Inclusive Cities project [European Commission CSO-LA/2017/154670-2/13]. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of IDS, Anthrologica or LSHTM.

KEEP IN TOUCH

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Richardson E (2022). Key Considerations: Drivers influencing vaccination-related behaviours among Ukrainian refugees in Poland. Social Science In Humanitarian Action Platfrom (SSHAP) DOI: https://doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2022.019

Published June 2022

© Institute of Development Studies 2022

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode