Effective child engagement strategies are essential to optimise the response to disease outbreaks and minimise their impact while ensuring children’s protection, well-being and resilience. When children understand disease outbreaks, they are better able to cope, contribute and recover. This promotes well-being and both protects children and recognises their agency. The Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) region is prone to disease outbreaks including Ebola and other haemorrhagic fevers, measles, cholera, anthrax and meningitis, all of which can disproportionately affect children. This brief explores why, when and how to engage children in the prevention, response and recovery stages. Drawing on published and grey literature, including project reports, and the authors’ extensive experience, it provides guidance to support the design and development of child-friendly communication and engagement strategies related to disease outbreaks. The brief covers efforts involving children and adolescents under 18 years and recommends three levels of participation. Organisations and practitioners can select a level based on organisational objectives, resources and readiness to engage with children.

Key considerations

- Populations of ESA have heightened vulnerability to disease outbreaks and children in the region are even more vulnerable to disease. This is why focusing on risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) in ESA is important, particularly in terms of protecting and engaging children.

- Engaging children in response efforts, especially RCCE, can mitigate the risks and adverse effects children face during outbreaks. Child-centred approaches prioritise the needs and rights of children and help those designing and implementing programmes to consider children’s experiences.

- Engaging and communicating with children before, during and after outbreaks enhances children’s agency, promotes well-being and protects children. When children understand disease and prepare for outbreaks, they are more resilient and better able to cope during an outbreak.

- Children can act as agents of change in their families and communities. Child-centred RCCE promotes actions that children, families and communities can take to prevent, respond to and recover from disease outbreaks. Children can share key health messages and promote healthy behaviours with their peers and relatives.

- Child-centred RCCE is responsive to the needs of children and their families and builds trust among family and community members. When trust is built, positive behaviour change is more likely to happen and be sustained.

- Child engagement strategies often make RCCE more inclusive. Storytelling, mapping, peer-based strategies, entertainment-education (‘edutainment’ – media designed to educate through entertainment) and other visual or participatory techniques can appeal to children as well as adults, and can be inclusive to those with disabilities or low literacy.

- RCCE should complement health, education, protection, and disaster preparedness and risk reduction efforts. Child-centred RCCE can build from school-based health education. Children’s clubs, community centres and child-centred organisations can advance RCCE within their own institutions and networks.

- More research into child engagement strategies is necessary as environmental, political, economic and digital landscapes shift. Additional research, including child-led research, on best practices in child engagement should be prioritised to ensure strategies meet communities’ evolving needs.

Box 1. Definitions

Risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) is a set of approaches focused on communicating risk. In the context of a disease outbreak, risk communication aims to ensure that people have the information they need to protect themselves from disease. This includes exchanging information between experts, officials and those at risk of contracting disease. Community engagement is a collection of approaches used by governments and partners to ensure that communities are working together to prevent, detect and address disease outbreaks.1

Child engagement and participation is an umbrella term for approaches that engage and involve children and adolescents (18 years and younger) in decisions and actions that affect their lives and communities. This includes preventing, detecting and addressing disease outbreaks. Child-centred disaster risk reduction (DRR) involves recognising and drawing on the rights, needs and capacities of children to reduce risk and enhance the resilience of communities and nations. It reduces risks to children while collaborating with them.2

Social and behaviour change (SBC) is a collection of tools and approaches that are used to systematically bring about change by addressing seemingly intractable challenges. These changes can happen at the individual, family or community level; within and among organisations, and at the national level.3 SBC and RCCE work best together to ensure that all aspects of human behaviour are considered in the development of systems to prevent, manage and respond to the spread of disease.

Impact of disease outbreaks on children

Children and adolescents aged 10 to 18 form over 50% of the population of many ESA countries. Approximately 215 million school-age children between the ages of 5-18 years old live in ESA.4 The region is also home to over two-thirds of the world’s children and adolescents living with HIV.4 In 2022, children under five accounted for 80% of all malaria deaths in the World Health Organisation’s Africa Region.5

Child engagement strategies are needed to effectively reach more of the region’s population. This is critical given the expected increase in outbreaks due to climate change, political instability, increased human-animal interaction and displacement. Despite the urgency, however, many SBC and RCCE efforts focus on adults.6 Children’s potential to accelerate household change, influence schools and mobilise communities to prevent, respond to and recover from outbreaks often remains untapped.

Children are adversely, and often disproportionately, affected by outbreaks, and their immature immune systems make them vulnerable to contracting disease.7 All aspects of children’s health and development are affected and they may experience delays in cognitive, language, and social development when interactions with their families and communities are disrupted by an outbreak.8 Children can become more vulnerable due to limited supervision by adults, and their lack of understanding and ability to comply with safe behaviours. They may also not disclose symptoms to adults that could require action.

The social and economic disruptions associated with disease outbreaks affect family and community stability, negatively impacting these interactions and children’s development. Schooling is often disrupted. Schools throughout the region were closed for an average of 22 weeks due to the COVID-19 pandemic and children in Uganda, Zimbabwe and Mozambique faced school closures exceeding 40 weeks.9 School closures continue to occur in the context of other outbreaks, such as the cholera outbreak in Zambia and Malawi in January 2024.9–11 In some locations, schools are environmentally safer places, providing better access to disease prevention resources such as clean water in comparison to community settings where children may have a higher risk profile. Disruption to schooling can therefore make children vulnerable to physical, psychological, and social impacts of disease, including malnutrition and poor mental health.

Some children are more vulnerable to disease than others. Exposure to poor diet in early childhood increases the risk of developing non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, during adulthood.12 Malnutrition and low immunisation rates increase vulnerability to disease outbreaks; populations with lower general health status are more vulnerable to multiple health impacts, including an elevated risk of infection in the event of a disease outbreak.

In Eastern Africa, 32.6% of children under five years of age experience stunting (low height-for-age) and 5.2% experience wasting (low weight-for-height).13,14 These children are at heightened risk of infection from any pathogen to which they are exposed. The developmental stage at which a child is exposed to disease outbreaks also has a major influence on its long-term effects on the child.15 Comorbidities (the coexistence of two or more diseases, states or processes in one person) such as HIV and COVID-19 – as well as other vulnerabilities linked to displacement, gender, and socio-economic status – exacerbate the impact of outbreaks on children and families. Comorbidities increase health spending by the health system and households, and can push families into further poverty.16

Disease outbreaks disrupt the provision of quality health care (particularly outreach services which focus on hardest-to-reach groups) and further exacerbate health challenges among children and the wider population. Some countries reduce routine child vaccinations during disease outbreaks, this can be due to financial and resource limitations and also due to routine healthcare being reduced to stop disease spread during lockdowns and other restrictions17. This can lead to the re-emergence of diseases such as polio and measles. COVID-19 had a severe impact on routine vaccination rates in the region with one review indicating a decline of between 10% to 38%.18 A total of 12.7 million children in Africa missed one or more vaccinations between 2019 and 2021, including 8.7 million children who did not receive a single dose of any vaccine.19 This has increased vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks: between January and March 2022 there was a 400% increase in vaccine-preventable diseases compared with the same period in 2021.20

Why engage with children?

Engaging children and adopting child-centred approaches are essential to improve the success of an outbreak response. Child-centred approaches prioritise the needs and rights of children, ensuring that programme planners and implementers hear children’s voices and consider their perspectives.21

More than just passive recipients of information, children can participate in and lead household and community health efforts. The Sendai Framework for 2015-2030, a global framework for disaster risk reduction (DRR), emphasises children as ‘agents of change’ in preventing, responding to and recovering from disasters such as epidemics.22 Numerous strategies, including those utilised within health, education, protection, and DRR provide a useful blueprint for disease outbreak efforts in the region. These strategies recognise the role that children play in many practices linked to disease, such as gathering water, preparing food, interacting with animals and caring for siblings.

Children can be effective agents of change, influencing their peers and families to adopt healthy behaviours, such as handwashing, social distancing, and wearing masks.23 A Tanzanian parent featured in a 2008 study on children’s health promotion commented:

We have all agreed that we can be educated by our children. In the old days, we could not accept, but nowadays we are progressive. We know the importance of cleanliness. One can find time to be educated by your own child or your neighbour’s child.24

Child-centred efforts at health promotion, such as those occurring in schools, often have a multiplier effect, with children relaying information they learn to families. A qualitative assessment of a school-based water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) intervention in Eastern Zambia found that mothers reported high levels of trust in the health information that students shared from school.25 School-based health promotion programmes often combine health education with a practical element, such as handwashing or using a bed net, which children can model in their home setting for parents and siblings.18,26

Child-friendly approaches may incorporate techniques that make SBC and RCCE more inclusive and effective for other community members across a broader population. Child- and adolescent-centred approaches often rely on art-based or visual approaches, storytelling, drama and other participatory techniques. These approaches may use simple messages, repetition, minimal text and emotion to appeal to children and adults, including individuals with low literacy and those with impaired vision or developmental disabilities.

Involving children in community engagement can also help to identify and address the unique needs of children through access to education, healthcare, and protection services.27 Child-centred approaches help to ensure that children’s rights are protected in the context of an outbreak. These rights include access to education and healthcare, protection from harm, respect for the views of the child, freedom of expression and access to information (Articles 12, 13 and 17 in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child).28 By engaging children in outbreak response design and implementation, and thereby prioritising the needs and rights of children, child-centred approaches help to prevent the spread of disease and promote healthy behaviours, while enhancing the well-being of children and their families.21

Engaging with children during prevention, response and recovery efforts

Child-centred SBC and RCCE should form part of prevention, response and recovery efforts. Effective SBC and RCCE prepares children prior to an outbreak. These efforts can prevent or mitigate outbreaks by promoting healthy behaviours and strengthening health knowledge among children and their families.

Prevention messaging should build on and complement existing health promotion or disaster preparation activities occurring within schools, community organisations and health centres. For example, school-based WASH programmes often promote hygiene practices such as handwashing, clean water, latrine use and safe food preparation. These practices prevent multiple diseases. School or community-based preparation for earthquakes, floods or drought provide children with valuable information on what to expect and do during crises. School health programming often includes linkages to the health system to facilitate vaccination campaigns and promote health-seeking behaviours.

SBC and RCCE can prepare children to respond to outbreaks. These efforts prepare children to navigate the rapid change that occurs during outbreaks or other disasters. Schools, early childhood centres, children’s clubs, youth centres or other child-centred groups have pre-existing networks that can be mobilised prior to or during disease outbreaks. Vaccination or other routine child health services can integrate child-centred communication around prevention and response. Coordinating with child-focused services or institutions prior to a disease outbreak reduces duplication and cost while increasing reach. These platforms provide rapid access to a broad audience of children and families.

During an outbreak, the objectives of SBC and RCCE often shift to accommodate multiple messages and objectives. Behaviour change may take on a new urgency. Additional safety measures may also be needed that considers public health guidance when designing child-focused SBC/RCCE interventions. For example, simulations and interactive workshops can be an effective way to prepare children for disease outbreaks and engage them in planning. These in-person interventions or public gatherings may not be appropriate during an outbreak. Communication efforts should focus on print, radio, television and mobile platforms, but these should be adapted with and/or for children. It is also important to consider how to reach children when schools (and other child spaces) are closed during outbreaks and how to support adults (caregivers and frontline workers) to work with children appropriately during an outbreak.

During and after an outbreak, children may confront loss and grief. Mental health must be considered in addition to physical health. SBC and RCCE efforts alongside mental health support services can support positive coping mechanisms among children and their families. Disease outbreaks may cause minor or major disruption, including the loss of parents or caregivers. Unfortunately, the behaviours needed to prevent disease may conflict with what children require for their healthy development, such as socialising and attending school. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a global case study in the difficult trade-offs that children and communities face during a disease outbreak. Other outbreaks, such as Ebola, have similarly disrupted customary practices linked to care, grief and mental health. SBC and RCCE efforts must balance these complex choices while supporting children to understand and navigate change.

Key moments to engage children

The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action outlines key moments (or opportunities) and topics to communicate to children.29 They explain that there are multiple key moments, during and after an outbreak. The content and context for each of these moments will vary widely and may represent interpersonal communication between a single adult and a single child or small group of children, or may happen at a broader community, or population level. Communication may include what precautions to take, specific details about the nature of the disease and how it may affect individual children or their family members. It may also focus on providing psychosocial support during or after an outbreak.

How to engage children: Levels of engagement

Several global frameworks shape concepts of child engagement and participation, including the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child and The Nine Basic Requirements for Meaningful and Ethical Children’s Participation by Save the Children.30,31 Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) enshrines a child’s right to express their views freely ‘in all matters affecting the child’.28 Subsequent articles of the UNCRC describe a set of civil rights and freedoms, including freedom of expression, which are collectively conceptualised as ‘child participation’.32 The UNCRC shifted the discourse on children away from a traditional view of children as property of their parents or passive recipients of aid to emphasise that children are active members in their family and communities with interconnected rights and responsibilities.33 For example, children’s right to know what causes disease accompanies their responsibility to avoid, to the extent possible, actions that spread disease.

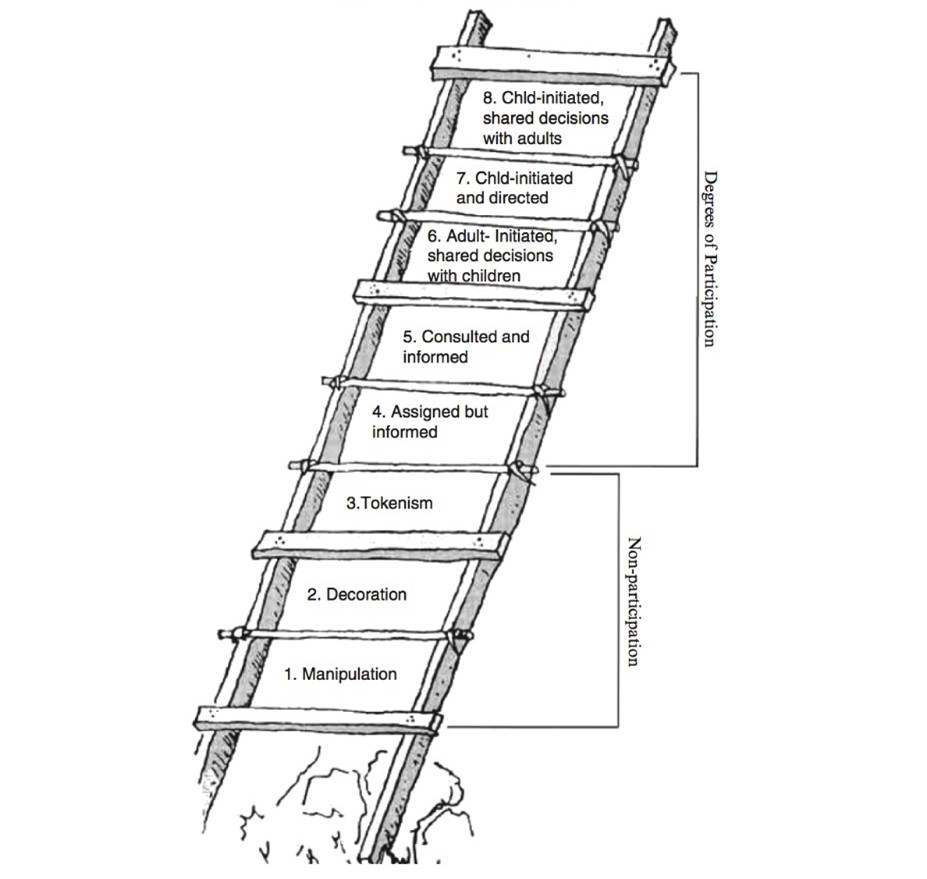

Degrees of child participation are often visualised as a ladder.34 The bottom rungs of the ladder include initiatives where children are not meaningfully engaged, such as manipulation, decoration and tokenism. Each rung of the ladder increases the degree of child engagement. At the highest levels, children and adults share decision-making.

Figure 1: The Ladder of Participation

Source: Hart, R. (1992) Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. UNICEF Innocenti Essays, No. 4, Florence, Italy: International Child Development Centre of UNICEF.

In this brief we simplify Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation, describing three levels of child participation:

- Level 1 strategies involve communicating with children in age-appropriate ways. For RCCE, this is often referred to as child-friendly communication.

- Level 2 strategies include activities that encourage children to take a specific action, such as sharing their perspectives and experiences related to health and disease.

- Level 3 strategies refer to longer-term processes whereby children participate or lead in preventing, preparing and responding to disease outbreaks.

These levels reflect child engagement strategies often employed in DRR and preparedness programmes. Strategies at each level are presented in the subsequent sections.

These three levels can guide decision-making around SBC and RCCE, with activities or campaigns engaging children across various levels. Children’s age and maturity affect the degree to which they can participate. For example, parent or caregiver engagement is a critical factor for engaging children under three years of age. All children, and particularly young children, benefit from modelling and repetition.

Dynamic approaches such as entertainment-education are designed to appeal to and generate conversations across households and communities. These approaches have the potential to hold audience attention, expose audiences to repeated messages and create an emotional investment in the topic.35 These can be aimed at children or young adults, for example entertainment-education programmes linked to sexual and reproductive health such as MTV Shuga originally launched in Kenya, and Intersexions and Soul Buddyz in South Africa, have been found to have a wide reach, strong viewer engagement and positive impact on young peoples’ health outcomes.36,37 Social media campaigns, podcasts and digital platforms can also be leveraged, such as Shujaaz Inc. in Kenya and Tanzania.

Local circumstances and resource availability may affect participation. It may be difficult to achieve the highest levels of participation during disease outbreaks or with time limitations. This reinforces the importance of engaging with children pre-crisis so that the necessary foundational work is in place and mutual trust is built. Prior experience or partnerships with child or adolescent-led organisations are necessary to move fast. Restrictions on in-person gatherings, such as those common during COVID-19, may complicate effective participation, particularly for young children, children with low literacy, and those without access to mobile technology. Involving child decision-making in programming may have implications for project budgets and deliverables, and must include suitable ethical consent and assent processes. Adults must plan appropriately, adapt and be prepared to cede control. As with the wider population, children need resources and an enabling environment to be able to implement preventative actions (i.e., they can only wear a face mask and drink safe water if they have access to these things). Instructing children to take action without ensuring they have the means to take action remains problematic.

Level 1 strategies for child-friendly communication

It is essential to consider children’s unique needs and interests in the development of SBC and RCCE interventions. Effective SBC and RCCE for children requires a tailored approach that considers their age, gender and cultural background.38 It is essential to use age-appropriate language and communication methods that are accessible to children, including those with disabilities, without reinforcing harmful stereotypes. This can include the use of storytelling, games, and other interactive activities that help to engage children and make the communication process more effective.5

Level 1 strategies ensure that children know about the disease outbreak and what they can do to remain safe. Some examples of RCCE activities that can be tailored to children’s unique needs and interests include:

- Storytelling: Storytelling is a traditional way to engage children and communicate important messages, and continues to be a highly effective strategy. Use stories to teach children about the risks of emergencies and how to protect themselves. For example, create a story about a family that prepares for an emergency by creating a disaster kit and practicing evacuation drills. Communication preferences and access to different communication channels is important when considering the medium through which to tell stories; radio, television, social media, comics and colouring books can serve to prepare children or help them understand disease outbreaks and associated behaviours.

- Personas: Relatable or aspirational characters, such as those utilised in cartoons, comics and animated features (like Super Sema) are designed to represent and reflect children’s experiences39. They can demonstrate how children can act to promote health. Bright colours, music, relatable dialogue and other communication elements signal to children of all ages that the persona will speak to them and their experience.

- Clear and simple messages: Effective RCCE does not need to be complicated. Often disease prevention depends on clear information repeated through multiple channels at key moments: many things can be done to prevent transmission, but there are a few critical things that must be done and these should be encouraged. Teachers can emphasise the importance of handwashing, and mass vaccination events can include a ‘children’s station’ where health service providers explain key behaviours with engaging demonstrations and simple language. The provision of supplies, such as bed nets or face masks, can also include basic education aimed at children.26

Level 1 strategies can operate in tandem with other levels. For example, stories and personas should incorporate details from children’s lives, ideally gained through consultation, research, testing and co-creation with children and adolescents.

Level 2 strategies to involve children

Level 2 strategies ask children to act. This action could involve recounting and reflecting on their experiences, such as when children are asked to relate their experiences, share their daily health practices or give opinions about community health. Level 2 strategies can be used in preparation, response and recovery stages. At the recovery stage, Level 2 activities can create safe opportunities for children to share difficult experiences.

Level 2 strategies also support behaviour change by asking children to engage in a desired behaviour, either temporarily or repeatedly, and can include the following actions:

- Consultation: Consultation with children adds a cognitive dimension to health communication that enhances memory and behaviour adoption. Children consider, externalise and ideally reflect on information about their lives. Adults can then use that information to design and improve strategies and actions.

- Art activities: Use art activities to help children express their feelings and emotions about emergencies. For example, ask children to draw pictures of what they think an emergency looks like or how they feel during an emergency. This can also help conceptualise the information and help children build upon the information they are receiving and problem solve.

- Games: Use games to teach children about emergency preparedness and response. For example, create a game where children identify hazards in their home and take steps to prevent the hazards.

- Role-play: Use role-play to understand existing household behaviours or ask children to share how existing behaviours could be improved, (e.g., through interactive street theatre). These forms of engagement often serve two purposes: to assess existing behaviours that may contribute to disease transmission; and to determine how to mitigate them.

- Drills: Drills and simulations prepare children for disasters including disease outbreaks. Drills may reduce children’s fear of the unknown by preparing them to take a specific and recommended action, often in groups, at the school, household or community level. More research is needed on drills, particularly those associated with disease. (One US-based study found school evacuation drills to be effective in increasing children’s knowledge without negatively impacting anxiety levels).

- Health literacy: Health literacy ensures that children, particularly older children and adolescents, possess the scientific knowledge necessary to understand disease. For younger children, this may include understanding basic concepts of nutrition, sanitation and hygiene. Health literacy reduces the risk of misinformation and disinformation prior to and during outbreaks. Children can critically evaluate information using their prior knowledge.

These strategies involve active learning, which improves memory by centring the experience within children’s bodies and engaging muscle memory. Modelling and repetition support actions to become automatic. For example, school-based efforts to promote handwashing often include modelling of handwashing by teachers followed by providing children with multiple handwashing moments throughout the day. Behavioural ‘nudges’ have also been shown to be highly effective to introduce and reinforce behaviours including hand washing.40

Several Level 2 strategies may be employed during child-centred research. For example, research may include activities whereby children draw, act out or tell stories about where they currently gather water or food. Follow-up activities may include asking children how they can find healthier sources of food or water. This can provide useful health information while engaging children to think critically about disease.

Level 3 strategies for child participation and leadership

Level 3 strategies engage children and adolescents in more meaningful and extensive ways. They may vary from Level 2 strategies by degree, approach and method. They may engage children over a longer period, allowing children to progress toward more active roles and responsibilities. Level 3 activities may include tasks or projects that children lead at home, at school or in the community. Level 3 activities may encourage children to choose how to respond to a particular issue or solve a problem in the community and can include:

- Co-creation: Co-creation is an approach that can help tailor communication strategies and other interventions to the developmental stages of children. Co-creation can be used to engage children in the design of RCCE or SBC materials. For example, children may suggest or create messages, art, activities and slogans, and host or contribute to radio programmes.

- Interactive workshops, simulations, mappings and action planning: Level 3 simulations and mappings build from those mentioned in Level 2. In these versions, children take active leadership roles in planning and executing the simulations and action planning. Through home, school or community mappings, children may gather data, lead surveys, assemble maps and analyse the results.

- Child researchers: Children can serve as co-researchers alongside adults or as researchers in their own right, increasing their sense of agency and ensuring their perspectives are explored.41 Child researchers can identify a topic or question, select research methods, undertake research activities and analyse results.

- Peer-based approaches: Peer-based health promotion, notably the child-to-child approach or child and adolescent clubs, have been in use for over 40 years42 with recent estimates noting that the child-to-child approach is used in 60 countries.43 Peer-based approaches support children to promote health with peers, including older and younger children. This communication may complement other activities, such as material distribution. For example, children may distribute water filters within the community and explain their use.

- Child, adolescent and youth-led movements and advocacy: Child-led movements may emerge independently, from peer-based approaches or civil society movements. RCCE may support children to mobilise and amplify their voices while addressing the root causes of disease outbreaks, such as climate change, displacement, sub-standard housing, or environmental degradation.

For Level 3 strategies, the adult’s role can vary based on the age of children, the nature of the group, and their availability to engage in independent or collaborative activities. Adults can be involved in inviting children, supporting group cohesion, giving initial guidance and periodically checking-in with the children. In other cases, such as with young children, adults may need to provide more extensive guidance and support.

Children’s capacity to lead depends on various factors: age, maturity, attention span and availability can all determine what is possible. Older children and adolescents may be able to lead multi-step processes, but often face greater demands on their time due to work and schooling. Mixed-age groups often work well in community settings where caring for siblings is common.

How to engage children: Guiding principles and processes

All levels of child engagement should follow basic ethical principles. Operating in the best interest of the child forms the basis for all child engagement. This means that engagement should always prioritise children’s needs and rights. The following considerations are important when engaging children at any level of participation:

- Health practices: Child engagement activities should respect local regulations around health, particularly during disease outbreaks. If in-person activities should be limited, consider conducting activities remotely or in settings where children are already gathered, such as schools.

- Safety: Safety can be promoted through organisational safeguarding measures and alignment with local child protection systems or organisations. Safeguarding measures reduce risks, including health risks, that children may encounter when participating in SBC and RCCE activities. Safeguarding should involve planning to prevent physical harm, sexual exploitation and abuse, and other abuses of power. Safeguarding also includes a plan for response, including referrals for additional support.

- Inclusion and non-discrimination: Children are a diverse group. Children’s capacities and vulnerability vary and may manifest differently across contexts. Gender, age, disability, ethnicity, language, level of schooling, and marital status may affect the extent to which children can participate. Using inter-personal communication and multiple media platforms, such as radio, print and television can facilitate inclusion. Strong visual components, as well as audio components, are useful for children with visual impairments as well as those who do not speak the dominant language. Diversifying representation of children, building in gender-transformative approaches, and avoiding common stereotypes can support inclusion.

- Respect: Effective child engagement begins from a shared understanding that children have valuable perspectives and capacities. On a practical level, respect is often communicated through tone of voice, body language and use of space. For example, utilising traditional classroom settings, where an adult stands at the front of the room and gives information to children may set the tone for an authoritarian approach that is not conducive to a respectful engagement. Conducting activities with children and adults at the same physical level, such as seated on mats in a circle on the floor, signals to children that all individuals are equally entitled to participate. Adults involved in child engagement approaches may need training in this area to ensure they understand and value the importance of demonstrating respect to children.

- Consent and assent: All activities, and particularly those that involve collecting information, photography or artwork from children, should proceed only after children and parents or caregivers give informed permission for children’s participation. Gathering consent or assent from children, parents or caregivers should be tailored to the local context and follow best practice. Children and caregivers should be informed how information, images or artwork will be used and final products, such as films or research reports, should be shared back with children and the broader community.

- Confidentiality: Children may not be aware of the possible consequences of sharing information about their lives, families and communities. Processes to ensure confidentiality of information should be established and enacted, with the understanding that confidentiality can be breached in exceptional circumstances if this is necessary to protect someone from harm. Children participating in group activities should also agree to respect confidentiality.

Conclusion

Children account for a significant proportion of the population in countries most affected by disease outbreaks in ESA. The region is vulnerable to disease outbreaks for many reasons, including geographic challenges, political instability and inadequate health system resourcing. This, coupled with children’s specific needs and vulnerabilities, means that children often experience more adverse effects than adults during a disease outbreak. When an outbreak happens, children’s development can be negatively affected; they are at high risk of losing the protective factors associated with families, peers, schools, and social support networks.

Child-centred approaches and strategies are, therefore, essential to ensure the protection, well-being and resilience of children in ESA when an outbreak occurs. Such approaches can also work to reduce the negative impact of disease outbreaks on the wider community. We know that children can be agents of change when involved in the design and implementation of SBC and RCCE activities, materials and actions at every stage of a disease outbreak – from prevention to recovery. Investment (in approaches, resources and skills) must be made to ensure the participation of children becomes the norm.

The SBC and RCCE communities of practitioners continue to develop new and innovative ways to engage with children and their support systems to improve health-seeking behaviour and respond to emergency situations. Child engagement is best implemented through strong partnerships between governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), child protection professionals and communities (including teachers, caregiver and peers).

Effective partnerships ensure better coordination and a more thoughtful and strategic response design. Digital and social media will continue to affect how children communicate with each other and with adults. Just as communities’ needs and priorities continue to shift with changes to the economic, political and environmental landscapes in ESA, there is still more to learn when it comes to what works effectively to engage children at every stage of disease outbreak. Better documentation of existing practices and more research into this area is, therefore, a priority.

Resources

The following resources provide guidance and examples of materials to enhance child protection, participation, communication and child-centred preparedness for outbreaks and other disasters.

The Inter Agency Standing Committee Guidelines on Working with and for Young People in Humanitarian and Protracted Crises was designed to be the ‘go-to’ guide for working with young people in such settings.44

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction shares a resource list on meaningful child engagement in DRR. Resources are indexed by topic and include child rights background; assessment and participation toolkits; child and youth-friendly tools and curricula; games and guidelines; and child protection and other sector-specific resources (e.g. WASH, health and nutrition, etc.).

The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action has produced 6 Mini-Guides on child protection, advocacy and child participation in outbreaks. The Mini-Guide series provides valuable information. Health sector stakeholders designing RCCE and SBC approaches may find the following most useful:

- Mini-Guide #4 Communicating with Children in Infectious Disease Outbreaks

- Mini-Guide #6 Prioritising Child Participation in Infectious Disease Outbreaks

The READY Initiative sponsored three webinars on children and disease outbreaks including a session on the centrality of children and their protection during outbreaks, child protection in treatment centres, and communicating with children in disease outbreaks.

Save the Children International has published The Nine Basic Requirements for Meaningful and Ethical Children’s Participation, which was endorsed by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child and is available in multiple languages.

UNICEF has published an overview of Social and Behaviour Change as well as case studies on SBC approaches, including peer-based methodologies.

References

- WHO. (n.d.). Risk Communications. Risk Communications. Retrieved November 25, 2023, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications

- Hore, K., Gaillard, J., Johnston, D., & Ronan, K. (2018). Child-Centred Risk Reduction Research-into- Action Brief: Child-centred disaster risk reduction. Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the Education Sector. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://www.preventionweb.net/files/61522_childcentreddrrr2abriefeng2018.pdf

- Bertram, K., Serlemitsos, E., & Clayton, S. (2016). What is Social and Behavior Change Communication. Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs. https://sbccimplementationkits.org/sbcc-in-emergencies/learn-about-sbcc-and-emergencies/what-is-social-and-behavior-change-communication/

- UNICEF. (2023). Regional Office Annual Report 2022: Eastern and Southern Africa. UNICEF ESARO. https://www.unicef.org/media/140591/file/ESA-2022-ROAR.pdf

- UNICEF. (2020, April 20). Malaria data snapshots: Snapshots from sub-Saharan Africa and added impacts of COVID-19. UNICEF Data: Monitoring the Situation of Women and Children. https://data.unicef.org/resources/malaria-snapshots-sub-saharan-africa-and-impact-of-covid19/

- Mora, C., McKenzie, T., Gaw, I. M., Dean, J. M., Von Hammerstein, H., Knudson, T. A., Setter, R. O., Smith, C. Z., Webster, K. M., Patz, J. A., & Franklin, E. C. (2022). Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nature Climate Change, 12(9), 869–875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01426-1

- Carsetti, R., Quintarelli, C., Quinti, I., Mortari, E. P., Zumla, A., Ippolito, G., & Locatelli, F. (2020). The immune system of children: The key to understanding SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility? The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(6), 414–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30135-8

- Alderman, H., Behrman, J. R., Glewwe, P., Fernald, L., & Walker, S. (2017). Evidence of Impact of Interventions on Growth and Development during Early and Middle Childhood. In D. A. P. Bundy, N. de Silva, S. Horton, D. T. Jamison, & G. C. Patton (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Health and Development (3rd ed.). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525234/

- UNICEF. (2022, March). Impact of Education Disruption: Eastern and Southern Africa- March 2022, Infographic. https://reliefweb.int/report/madagascar/impact-education-disruption-eastern-and-southern-africa-march-2022#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20schools%20in%20the,Global%20Monitoring%20of%20School%20Closures.

- Lusaka Times. (2024, January 5). Zambia: Government Postpones School Opening Due to Cholera Surge. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2024/01/05/government-postpones-school-opening-due-to-cholera-surge/

- Reuters. (2023, January 3). Malawi delays reopening schools as cholera cases surge | Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/cholera-deaths-surge-malawi-keeping-schools-closed-2023-01-02/

- Dabelea, D., Hamman, R. F., & Knowler, W. C. (2018). Diabetes in Youth. In C. C. Cowie, S. S. Casagrande, A. Menke, M. A. Cissell, M. S. Eberhardt, J. B. Meigs, E. W. Gregg, W. C. Knowler, E. Barrett-Connor, D. J. Becker, F. L. Brancati, E. J. Boyko, W. H. Herman, B. V. Howard, K. M. V. Narayan, M. Rewers, & J. E. Fradkin (Eds.), Diabetes in America (3rd ed.). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567997/

- Global Nutrition Report. (2022). Global Nutrition Report | Country Nutrition Profiles. Retrieved December 19, 2023, from https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/eastern-africa/

- Quamme, S. H., & Iversen, P. O. (2022). Prevalence of child stunting in Sub-Saharan Africa and its risk factors. , Volume 42, 2022. Pages 49-61, ISSN ,. Clinical Nutrition Open Science, 42, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutos.2022.01.009

- Sly, P. D., & Flack, F. (2008). Susceptibility of Children to Environmental Pollutants. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1140(1), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1454.017

- Watts, C., Atieli, H., Alacapa, J., Lee, M.-C., Zhou, G., Githeko, A., Yan, G., & Wiseman, V. (2021). Rethinking the economic costs of hospitalization for malaria: Accounting for the comorbidities of malaria patients in western Kenya. Malaria Journal, 20(1), 429. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03958-x

- Das, U., & Fielding, D. (2024). Higher local Ebola incidence causes lower child vaccination rates. Scientific Reports, 14, 1382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51633-3

- Dalton, M., Sanderson, B., Robinson, L. J., Homer, C. S. E., Pomat, W., Danchin, M., & Vaccher, S. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 on routine childhood immunisations in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(8), e0002268. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0002268

- United Nations Children’s Fund. (2023). The State of the World’s Children 2023: For every child, vaccination. UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight. https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2023

- WHO Africa. (2022). Vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks on the rise in Africa. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/news/vaccine-preventable-disease-outbreaks-rise-africa

- Save the Children. (2007). Child Protection in Emergencies Priorities, Principles and Practices. The International Save the Children Alliance. https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/global/reports/education-and-child-protection/CP-in-emerg-07.pdf

- United Nations. (2015). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030

- Milakovich, J., Simonds, V., Held, S., Picket, V., LaVeaux, D., Cummins, J., Martin, C., & Kelting-Gibson, L. (2018). Children as Agents of Change: Parent Perceptions of Child-driven Environmental Health Communication in the Crow Community. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 11(3), 115–127.

- Mwanga, J. R., Jensen, B. B., Magnussen, P., & Aagaard-Hansen, J. (2008). School children as health change agents in Magu, Tanzania: A feasibility study. Health Promotion International, 23(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dam037

- Bresee, S., Caruso, B. A., Sales, J., Lupele, J., & Freeman, M. C. (2016). ‘A child is also a teacher’: Exploring the potential for children as change agents in the context of a school-based WASH intervention in rural Eastern Zambia. Health Education Research, 31(4), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyw022

- Koenker, H., Worges, M., Kamala, B., Gitanya, P., Chacky, F., Lazaro, S., Mwalimu, C. D., Aaron, S., Mwingizi, D., Dadi, D., Selby, A., Serbantez, N., Msangi, L., Loll, D., & Yukich, J. (2022). Annual distributions of insecticide-treated nets to schoolchildren and other key populations to maintain higher ITN access than with mass campaigns: A modelling study for mainland Tanzania. Malaria Journal, 21(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04272-w

- Moore, T., McDonald, M., McHugh-Dillon, H., & West, S. (2016). Community engagement Practice Guide. Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://aifs.gov.au/resources/practice-guides/community-engagement

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Pub. L. No. General Assembly Resolution 44/25 (1989). https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

- The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action. (2022). Child Protection in Outbreaks: Communicating with children in infectious disease outbreaks (Mini-Guide: Communicating). https://alliancecpha.org/en/miniguide_4

- Save the Children. (2021). The Nine Basic Requirements for Meaningful and Ethical Children’s Participation. Save the Children’s Resource Centre. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/basic_requirements-english-final.pdf/

- African Union. (1990). African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child | African Union. https://au.int/en/treaties/african-charter-rights-and-welfare-child

- Save the Children. (n.d.). Child Participation. Child Rights Resource Centre. Retrieved February 2, 2024, from https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/topics/child-participation/

- Duramy, B., & Gal, T. (2020). Understanding and implementing child participation: Lessons from the Global South. Children and Youth Services Review, 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105645

- Hart, R. A. (1992). Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship (No. 4; Innocenti Essay). https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/100-childrens-participation-from-tokenism-to-citizenship.html

- Grady, C., Iannantuoni, A., & Winters, M. S. (2021). Influencing the means but not the ends: The role of entertainment-education interventions in development. World Development, 138, 105200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105200

- Kyegombe, N., Zuma, T., Hlongwane, S., Nhlenyama, M., Chimbindi, N., Birdthistle, I., Floyd, S., Seeley, J., & Shahmanesh, M. (2022). A qualitative exploration of the salience of MTV-Shuga, an edutainment programme, and adolescents’ engagement with sexual and reproductive health information in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 30(1), 2083809. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2022.2083809

- Letsela, L., Jana, M., Pursell-Gotz, R., Kodisang, P., & Weiner, R. (2021). The role and effectiveness of School-based Extra-Curricular Interventions on children’s health and HIV related behaviour: The case study of Soul Buddyz Clubs Programme in South Africa. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 2259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12281-8

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2019). Words into Action Guidelines: Engaging Children and Youth in Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience Building. https://www.undrr.org/words-into-action/engaging-children-and-youth-disaster-risk-reduction-and-resilience-building

- Tai. (n.d.). Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://www.tai.or.tz/about-us

- USAID, IDInsight, & UNICEF. (2020). Installation Guide to Handwashing Nudges. https://www.idinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/HandwashingNudgesHowToBookletInternational26.09.2020-2.pdf

- Kim, C.-Y., Sheehy, K., & Kerawalla, C. (2017). Developing children as researchers: A practical guide to help children conduct social research. Routledge.

- Pridmore, P., & Stephens, D. (2000). Children as Partners for Health: A Critical review of the child-to-child approach. Zed Books.

- Johnsunderraj, S., Francis, F., & Prabhakaran, H. (2023). Child-to-child approach in disseminating the importance of health among children –A modified systematic review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 12(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_8_23

- IASC. (n.d.). With us & for us: Working with and for Young People in Humanitarian and Protracted Crises, UNICEF and NRC for the Compact for Young People in Humanitarian Action.

Author: This brief was written by Elena Reilly (Anthrologica, [email protected]), Elizabeth Serlemitsos (Johns Hopkins University, [email protected]), and Julieth Sebba Bilakwate (Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, [email protected])

Acknowledgements: Input was received from a range of experts, and the brief was reviewed by Stephanie Bradish (Save the Children), Alexis Decosimo (Independent Consultant), Hana Rohan (Independent Consultant) Rachel James (UNICEF), Catherine Grant (IDS) and Juliet Bedford (Anthrologica), and edited by Georgina Roche (SSHAP editorial team).

Suggested citation: Reilly, E., Serlemitsos, E. and Bilakwate, J. (2024). Key Considerations: Child Engagement in the Context of Disease Outbreaks in Eastern and Southern Africa. Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP). www.doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2024.007

Published by the Institute of Development Studies: April 2024.

Copyright: © Institute of Development Studies 2024. This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). Except where otherwise stated, this permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.

Contact: If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Juliet Bedford ([email protected]).

About SSHAP: The Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica , CRCF Senegal, Gulu University, Le Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, University of Ibadan, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

Keep in touch

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter