The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected young people across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Since 2020, young people in LAC have faced many challenges, including adjusting to virtual learning environments, experiencing depression and loss, becoming unemployed, and more, with no clear sign of relief. Public health and social measures instituted by governments, while necessary to slow transmission of COVID-19, largely failed to consider the needs of young people. With few supports, young people were left to navigate the pandemic on their own.

As the pandemic response evolves, key questions for practitioners and governments arise, including: What lessons can be learned from youth perspectives on the COVID-19 response thus far? And how can we better engage young people as a part of pandemic preparedness and response now and in the future?

This brief draws on academic and grey literature exploring how COVID-19 affects young people, as well as literature describing the pandemic response in LAC and other regions. It offers considerations on how to engage youth by viewing them not only as a part of the affected population, but also as partners in the response. The brief is intended to guide humanitarian actors, public health officials, youth advocates, community engagement practitioners, and others involved in the COVID-19 response. It also adds to the existing evidence base on the impact of COVID-19 on young people. These lessons are useful to strengthen preparedness and programmatic responses to outbreaks.

Young people are categorised as individuals between the ages of 10 and 24 years. Key considerations are shared for adolescents (aged 10–19) and youth (aged 15–24). Barbados and Brazil were chosen as case studies given their large number of young people (comprising just under 20 percent of the population in both countries), as well as their differing national responses to COVID-19, despite facing similar challenges during the pandemic.

This brief is part of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP) series on social science considerations relating to COVID-19. It is part of a series authored by participants from the SSHAP Fellowship, Cohort 2, and was written by Stephanie Bishop and Juliana Corrêa. Contributions were provided by subject matter experts from UNICEF, the Barbados Ministry of Youth, and University of Espírito Santo. The brief was supported by the SSHAP team at the Institute of Development Studies and edited by Victoria Haldane (Anthrologica). This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Adolescents (aged 10–19)

- Provide community-based spaces for adolescents to safely share their experiences. Spaces that provide adolescent-friendly communication (both in terms of content and delivery platforms) allow young people to interact with peers, express themselves openly, and learn from peer experiences of coping during the pandemic. These settings should be virtual, mobile, and managed by community members trained in providing mental health and psychosocial support.

- Increase delivery of health and family life education programmes. Tools and resources should be offered in communities to support positive caregiver–child relationships. These should focus on reinforcing positive behaviours and managing difficult behaviours. For younger adolescents in particular, tools should focus on creating play routines, using play to reinforce preventative actions, such as hand washing, and encouraging conversations about COVID-19.

- Include adolescents outside of family care in response efforts. Adolescents living in orphanages, residential care, and other forms of institutional care have unique needs that must be considered both during the initial pandemic response and when essential services are being restored. Where institutionalisation is necessary, financial support and psychosocial services should be provided to families to help them support adolescents who lost their primary caregivers.

Youth (aged 15–24)

- (Re)Build trust with young people via youth networks. Youth networks and community groups could be supported by the government but managed by trusted community youth leaders. Spaces must be created where government officials listen to young people’s concerns and needs. Youth groups could also partner with government agencies to ensure pandemic responses adopt participatory approaches with youth for planning, coordination, and feedback mechanisms.

- Promote funding for activities developed by community-led organisations. Recognise and partner with existing organisations to engage with and mobilise young people. These channels should be maintained throughout the pandemic to facilitate scientific communication and dissemination, mitigate the impact of fake news, and support COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

- Encourage collaboration between young people and research institutions. The views, experiences, and perspectives of young people are critical to ensuring a robust evidence base to guide decision-making during the pandemic. Involving young people in research design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination of findings can strengthen interventions, programmes, and policies.

- Mobilise young people to reach other youth and the most vulnerable in communities. Youth can share public health messaging, protective equipment, or other supplies with community members. In doing so, they offer a meaningful contribution to the national COVID-19 response, while also developing their own skillsets.

COVID-19 IN BARBADOS AND BRAZIL

Since the start of the pandemic in 2020, there have been 65.4 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 1.65 million deaths reported in the LAC region.[1] Globally, LAC accounts for approximately 15 percent of all reported COVID-19 cases globally, and 28 percent of all reported deaths due to COVID-19.

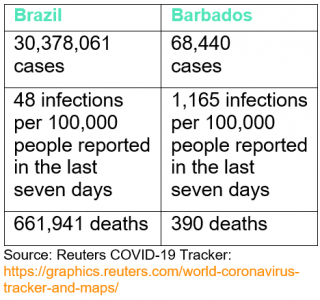

The first two cases of COVID-19 in Barbados were confirmed on 17 March 2020.[2] In the English-speaking Caribbean, Barbados has reported the second highest number of cases, with 68,440 COVID-19 infections reported between March 2020 and the end of April 2022.3 Since March 2020, the country also reported 390 deaths due to COVID-19. By the end of April 2022, an average of 477 new infections were reported daily.[3]

The first case of COVID-19 in LAC was reported in São Paulo state, Brazil on 26 February 2020. In March 2020, the Ministry of Health reported the first cases of community transmission.[4] Since then, Brazil has experienced devastating waves of COVID-19 infections and has reported the highest case numbers and deaths in the region – nearly 30 million cases and over 660,000 deaths due to COVID-19. However, as of late April 2022, Brazil reported a decrease in new infections, with an average of 14,691 daily reported cases.

Response to the pandemic in Barbados

Following the first confirmed case of COVID-19, the Government of Barbados declared a public health emergency in mid-March 2020. Shortly after a nationwide curfew was implemented and borders closed to incoming travellers. In June 2020, following an initial decrease in reported COVID-19 cases, some restrictions were relaxed.

Box 1. COVID-19 situation

Yet, schools, businesses, and other economic and social activities remained closed across the country. By December 2020, the number of active cases in Barbados rapidly increased, which prompted the government to impose a night curfew in January 2021. This curfew remained in place, with some modifications, until March 2022.

Given the widespread economic repercussions of the pandemic, Barbados implemented social protection measures to support households and maintain livelihoods. Social protection was offered through existing channels, or through programmes created as part of the COVID-19 response. One such measure was the Household Survival Programme, which provided monthly financial assistance to 1,500 families identified as the most vulnerable. Under the Adopt-a-Family Programme, the government also worked to provide monthly assistance to vulnerable families. The programme was funded by a mix of public funding, as well as corporate and individual donations. Aside from financial assistance, the government distributed food packages to vulnerable households during the national curfews. However, a Livelihoods Impact Survey revealed that only one-tenth of respondents received government assistance.[5]

Response to the pandemic in Brazil

In Brazil, pandemic response efforts are shared by different institutions at the federal, state, and municipal levels. Specific committees to manage the COVID-19 crisis were created in Brazil’s 27 states, as well as in the Ministry of Health. In response to rising case numbers in 2020, most states and municipalities quickly closed schools and businesses and cancelled large social events. Protocols were created for hospitals and the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) played a vital role in provision of healthcare for people with COVID-19, while also trying to maintain routine health service delivery.

Nevertheless, a lack of national coordination and leadership has challenged the COVID-19 response in Brazil. From the earliest stages of the pandemic, there were disputes between the federal government, states, and municipalities over how to best mount a response.[6],[7],[8] For example, at the national level, President Bolsonaro opted not to follow World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines or implement evidence-based health policy. Throughout the pandemic, the president routinely made arguments against public health measures. As a result, between 2020 and 2021, the leadership of the Ministry of Health changed four times due to disagreements about the COVID-19 response. Indeed, the pandemic response was used as a political instrument in Brazil. Despite this controversial approach to pandemic response, some economic and social assistance programs were offered to the public. For example, a cash transfer programme was developed in 2020 to alleviate the economic losses faced by the most vulnerable groups in Brazil. In April 2020, Emergency Aid was sanctioned to supplement the income of informal workers and those with limited social protection during the pandemic period.[9]

International aid to support the COVID-19 response in Barbados and Brazil

The response in both countries was also supported by UNICEF, WHO, other United Nations agencies, and international aid groups. These efforts focused on outbreak control, as well as mitigation of the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic and containment measures. Activities included strengthening risk communication and community engagement (RCCE), improving infection prevention and control measures, supporting continued access to essential health and nutrition services, education, social protection and gender-based violence services, and facilitating evidence generation for public health decision-making.[10]

IMPACT OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON YOUNG PEOPLE

Young people are particularly affected by the social and economic upheaval caused by the pandemic and response efforts. Many young people experienced, and continue to experience, intersecting factors that amplify their vulnerabilities.[11] These include, educational gaps, mental health conditions, economic disadvantages, and loss of caregiver support.

Adolescent education

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated challenges in access to education for young people, particularly for those most vulnerable. UNESCO estimates that 97 percent of students globally experienced some disruption to their education.[12]

However, even before the pandemic, access to education was limited for many across the LAC region. COVID-19 has in turn created deeper educational inequities, with at least a third of countries in the region reporting lengthy school closures. As a result, children in LAC lost, on average, 200 in-person days of education – four times more than the rest of the world.14 In both Barbados and Brazil, schools were closed for approximately 37 weeks during the period between March 2020 and March 2022.

The pandemic also underscored educational inequity in the region. While in many countries online learning replaced in person classes, current estimates report that only one-third of children in LAC have access to quality distance learning. Accessing distance education is more challenging for those with additional vulnerabilities including disabilities, ethnicity, geographic remoteness or dislocation because of migration, and digital inequalities.

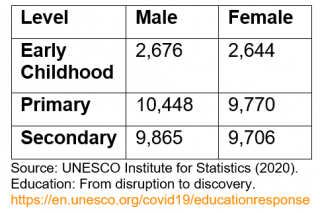

Box 2. Number of students out-of-school due to COVID-19 school closures in Barbados, by gender

Box 2 presents an overview of the sex-disaggregated data at the different school levels in Barbados. Evidence suggests a gender disparity in school attendance, with more boys than girls out of school as a result of COVID-19 measures.[13] In Brazil, it is estimated that in November 2020 over 5 million girls and boys aged 6–17 did not have access to education.[14] In Brazil, boys make up the majority of out-of-school children and adolescents. Within the 6–14 age group, for example, the number of out-of-school boys is almost 10 percent higher than out-of-school girls. Black, brown, and Indigenous young people have the worst out-of-school rates amounting to over 70 percent of the entire out-of-school population.

Mental health of adolescents and youth

Schools are not only important for building cognitive skills, but also play a critical role in young people’s social and emotional development. Abrupt school closures, coupled with other restrictive measures, had a significant and negative impact on the mental health of young people during and after periods of isolation.[15],[16] In addition to direct physical health effects, a more immediate health consequence of the pandemic has been the adverse impact on young people’s mental well-being, including the ability to cope, worries and levels of psychological distress.

School closures have not only disrupted children’s education but have resulted in a huge increase in time that children spend at home, especially since closures are accompanied by restrictions on socialising with family members and friends outside the home and participating in school-based programmes geared towards cultivating positive behavior. These lockdowns and restrictions often lead to frustration and increase tensions between parents and children.

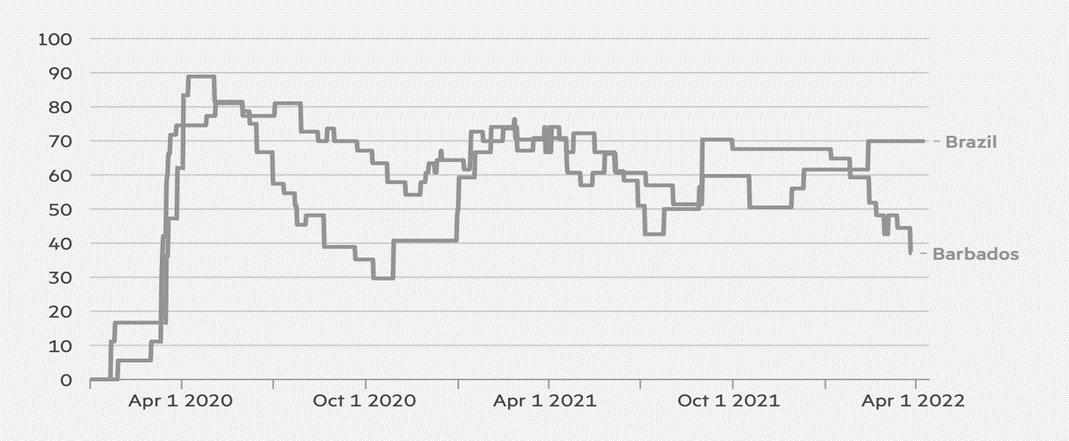

Yet, governments in the LAC region have been cautious in easing lockdown measures, in part because of recurring spikes in cases and low COVID-19 vaccine uptake among the eligible population. Figure 1 uses the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index[17] to present the evolution of lockdowns in Barbados and Brazil from April 2020 to April 2022. The index records the strictness of ‘lockdown style’ policies that restrict people’s behaviour. It is calculated using containment and closure policy indicators, plus an indicator recording public information campaigns.

A 2021 rapid assessment found that 27 percent of young people reported feeling anxiety, and 15 percent reported experiencing depression in the previous seven days. The highest proportion of depression and anxiety reported was among women and girls. For 30 percent of respondents, the main factor influencing their current emotions was the economic situation. The impact of the crisis on the psychosocial well-being of young people also varied depending on their household and individual circumstances. Well-being was reportedly shaped by income loss, housing quality, the presence of existing medical conditions, vulnerable persons in the household, and loss of loved ones.

Economic participation of young people

School closures and other restrictive policies also threaten the ability of young people to build skills and participate in the labour market, further diminishing long-term human capital and economic opportunities across the region.[18]

The average unemployment rate for young people in LAC aged 15–24 reached 23.8 percent at the beginning of 2021, an increase of more than three percentage points compared with pre-pandemic estimates.[19] At the same time, the youth labour force participation rate contracted, falling by approximately three percentage points to 45.6 percent in the first quarter of 2021.22 It is estimated that between 2 to 3 million young people were kept out of the labour force because of limited job opportunities during this time. At the end of 2021, the percentage of young people aged 15–24 who are not in education, employment, or training was around 25 percent in both Barbados and Brazil.[20] The youth unemployment rate for both countries was 30 percent in early 2021,23 however, this figure is projected to rise by five to seven percentage points in 2022.

Young people make up most of the economically active population in the LAC region, largely working in sectors severely affected by the COVID-19 crisis (e.g., restaurants, hotels, and the entertainment industry). During the height of the pandemic, young people looking for jobs reported a lack of adequate employment because of business closures and economic stagnation.[21] They are now facing a higher risk of job and income loss. Those who were employed throughout the pandemic, primarily those engaged in informal labour, risked increased exposure to COVID-19 on crowded public transportation and at the workplace. These same workers had limited access to personal protective equipment, such as masks.[22]

Young people in residential care

The high number of deaths due to COVID-19 in the region has caused many young people to lose their primary caregiver or caregivers. It is estimated that between March 2020 and April 2021, over 1.1 million children globally experienced the death of both primary caregivers, including at least one parent or custodial grandparent.[23] Importantly, in many LAC countries, grandparents play an important role as caregivers. For example, in Brazil 70 percent of children receive financial support from a grandparent.[24] Given the vulnerability of older adults to adverse outcomes from COVID-19, many children lost crucial familial sources of support during the pandemic. In Brazil, it is estimated 130,363 children and adolescents became orphans between March 2020 and April 2021.

As the number of orphans grows in LAC, increasing numbers of children and adolescents are placed in residential care. In Brazil, a national survey found that restrictive public health policies negatively impacted young people living in residential care, as they were unable to have family visits, socialise with friends, or partake in daily external activities, such as school, sports, and leisure.[25] For practitioners, there was a need to adjust interventions offered in residential care given restrictions on external activities. Ensuring contact with family members was challenged during the pandemic by the switch to online communication platforms for visits. For families without internet access or remote connection, maintaining contact with young people in residential care was challenging.

DRIVERS OF THE PROBLEM

Public health and social measures to limit viral transmission, while necessary, disrupted life for young people and further amplified the challenges they face, while also exposing them to greater scrutiny by the media. However, young people were routinely excluded from pandemic response research, as well as programme development, implementation, and evaluation.

Media portrayals of young people

During the pandemic, young people in LAC were largely portrayed in the mainstream media as being irresponsible and ‘non-cooperative’ with public health recommendations.[26] For example, in Barbados at the beginning of the pandemic, a significant portion of the media and public health attention framed young people as ‘spreaders of the virus’, and as being largely responsible for the second wave of COVID-19 throughout the country. They were accused of being careless, irresponsible, and dismissive of the risks. Generalising young people as a homogenous group added increased complexities to an already challenging pandemic response, and undermined public health communication efforts with young people.

Lack of trust in government

A society’s trust and confidence in government are crucial when it comes to mounting an effective collective response to an infectious threat.[27] However, global evidence suggests that experiencing an epidemic can negatively affect an individual’s confidence in political institutions and diminishes trust in political leaders. Diminished trust compromises a society’s collective response capacity and undermines efforts to control epidemics.

In 2021, evidence from 21 countries found that adolescents and young people trusted science and international media over governments as sources of safe information compared to adults. [28] In Brazil, 14 percent of adolescents and young people trust the government as a source of information, compared to 23 percent of adults. In Barbados, there is no documented evidence of mistrust, but anecdotal reports from youth groups and disadvantaged youth emphasises feeling ‘left out’ during response actions.

Limited COVID-19 responses for youth

Overall, national pandemic response measures at the height of the pandemic in both Brazil and Barbados were not tailored to young people. However, there were several initiatives supported by the private sector and international development partners that sought to involve young people.

One such initiative was Mission Critical: Saving Lives Risk Communication and Community Engagement response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[29] Coordinated by the Barbados Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the programme aimed to identify the needs of persons affected by COVID-19, strengthen community action towards improved health behaviours, and create collective responsibility for population health and well-being. Over 300 young people from vulnerable communities across Barbados, as well as university students, volunteered to work in the programme. Many reported that participating was an opportunity to contribute to national efforts, while also serving their communities.

The Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) and UNICEF also hosted a series of Youth Hangouts[30] across the LAC region. These were focused on providing virtual platforms for young people. Each week for four months, adolescents and youth were invited to participate in hour-long sessions where they could share their challenges and coping mechanisms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Brazil’s favelas, young people played a leading role in the response at the community level amid limited government support and access to assistance. The recently published Resilient Realities case study on the impact of the pandemic on Brazil’s youth organisations, shows that these initiatives gave voice to some of the youth who organised COVID-19 fundraising and relief work31. In Jacarézinho Favela for instance, youth networks raised more than 120,000 reals (about US$ 24,000) to buy food supplies for more than 2,000 families. In Santa Cruz, young people supported more than 3,000 families with food and other essential items. In the Cidade de Deus Favela, widely known as the City of God, a youth-led group organised more than 10,000 food basket donations for their community.

CONCLUSION

In Barbados and Brazil, and across LAC, young people have endured multiple lockdowns, movement restrictions, and drastic changes to their way of life. While both countries implemented social protection measures to support vulnerable households, these did not adequately consider the needs of young people, nor were supports offered that address the unique challenges of young people. As a result, disparities and inequalities are deepening for young people across the region. Pandemic response measures must recognise the challenges faced by adolescents and youth, and interventions must be tailored to their needs and developed in partnership with them. Greater collaboration with young people is an important step towards strengthening pandemic preparedness and response.

REFERENCES

[1]. Schwalb, A., Armyra, E., Méndez‐Aranda, M., and Ugarte‐Gil, C., ‘COVID‐19 in Latin America and the Caribbean: Two years of the pandemic’, Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 1 , no. 6, 2022, pp. 1-19.

[2]. Gooding, K., ‘Update: Barbados has its First Two Confirmed Cases of COVID-19: Loop Barbados’, Loop News https://barbados.loopnews.com/content/barbados-awaiting-covid-19-update accessed 15 April 2022

[3]. COVID-19 situation data covers period March 2020–April 2022 for both Brazil and Barbados

[4]. De Melo, C. M. L., Silva, G. A. S., Melo, A. R. S., and De Freitas, A. C., ‘COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: the Brazilian reality from the first case to the collapse of health services’, Sci ELO Brazil, vol. 92, no. 4, 2020, pp. 1-14.

[5]. World Food Programme, ‘Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security & Livelihoods Impact Survey. BARBADOS Summary Report’ https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000128070/download/ accessed 15 April 2022

[6]. Henriques, C. M. P., & Vasconcelos, W., ‘Crises dentro da crise: respostas, incertezas e desencontros no combate à pandemia da Covid-19 no Brasil’, Estudos Avançados, vol. 34, no. 99, 2020, pp.25-44 accessed 25 April 2022

[7]. Greer, S. L., King, E. J., da, F. E. M., and Peralta-Santos André. Coronavirus politics: The comparative politics and policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press, 2021, pp. 3-33.

[8]. Matta, G. C., Rego, S., Souto, E. P., and Segata, J., ‘Os impactos sociais da covid-19 no Brasil: Populações Vulnerabilizadas e respostas à Pandemia’, SciELO Books, 2021, pp. 15-24.

[9]. Garcia, M. L., et al. ‘The COVID-19 Pandemic, Emergency Aid and Social Work in Brazil’, Qualitative Social Work, vol. 20, no. 1-2, 2021, pp. 356–365

[10]. UNICEF LACRO, ‘Impact of COVID19 on Children and Families in Latin America and the Caribbean’, https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/media/14531/file accessed 10 November 2021

[11]. Brooks, S.K., et al. ‘The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and how to Reduce it: Rapid Review of the Evidence’, The Lancet, vol. 395, no. 10227, 2020, pp. 912–920

[12]. UNESCO Institute for Statistics, ‘Dashboards on the Global Monitoring of School Closures caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic’ https://covid19.uis.unesco.org/global-monitoring-school-closures-covid19/ accessed 13 November 2021

[13]. Blackman, S., ‘The impact of COVID-19 on education equity: A view from Barbados and Jamaica’, Prospects (Paris), 2021, pp. 1-14.

[14]. UNICEF and Cenpec Educação, ‘Out-of-school Children in Brazil: A Warning about the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Education’, https://www.unicef.org/brazil/media/14881/file/out-of-school-children-in-brazil_a-warning-about-the-impacts-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-education.pdf accessed 20 April 2022

[15]. Singh, S., et al. (2020). ‘Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations’, Psychiatry Research, vol. 293, no. 113429, 2020, pp. 1-9

[16]. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, ‘Pandemic School Closures: Risks and Opportunities’, The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, vol. 4, no. 5, 2021, p. 341

[17]. Hale, T., et al. ‘A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies: Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker’ https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/covid-19-government-response-tracker accessed 20 April 2022

[18]. d’Orville, H., ‘COVID-19 Causes Unprecedented Educational Disruption: Is There a Road Towards a New Normal?’, Prospects, vol. 49, no. 1–2, 2020, pp. 11–15

[19]. International Labour Organization, ‘The Lockdown Generation: Disarming the Timebomb. ILO’ https://www.ilo.org/caribbean/newsroom/WCMS_816641/lang–en/index.htm accessed 20 April 20

[20]. International Labour Organization, ‘Unemployment Youth Total (% of total labour force ages 15-24) ILO modeled estimates’, ILOSTAT https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ accessed 19 April 2022

[21]. ILO & OECD, ‘The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Jobs and Incomes in G20 Economies’ https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/how-the-ilo-works/multilateral-system/g20/reports/WCMS_756331/lang–en/index.htm accessed 16 November 2020

[22]. Guimarães, R. M., et al., ‘Younger Brazilians hit by COVID-19 – what are the implications?’, The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, vol. 1, 100014, 2021, pp. 1-2.

[23]. Hillis S.D., et al., ‘Global Minimum Estimates of Children affected by COVID-19-associated Orphanhood and Deaths of Caregivers: A Modelling sSudy’, The Lancet, vol. 398, no. 10298, 2021, pp. 391–402.

[24]. Camarano, A.A., ‘Depending on the Income of Older Adults and the Coronavirus: Orphans or Newly Poor?’ Cien Saude Colet, vol. 25 (suppl 2), 2020, pp. 4169–4176

[25]. Bernardi, D.C.F., ‘Levantamento nacional sobre os serviços de acolhimento para crianças e adolescentes em tempos de COVID-19’, São Paulo, NECA, Movimento Nacional Pró-Convivência Familiar e Comunitária e Fice Brasil, https://www.neca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/E-book_1-LevantamentoNacional.pdf accessed 16 April 2022

[26]. Barrucho, L., ‘COVID-19: o que explica mais infecções e mortes entre os jovens no Brasil’, BBC News Brazil https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-56931387 accessed 9 November 2021

[27]. London School of Economics and Political Science, ‘The Political Scare of Epidemics: Why COVID-19 is Eroding Young People’s Trust in their Leaders’ https://www.lse.ac.uk/research/research-for-the-world/politics/the-political-scar-of-epidemics-why-covid-19-is-eroding-young-peoples-trust-in-their-leaders-and-political-institutions

[28]. UNICEF, ‘The Changing Childhood Project’ https://changingchildhood.unicef.org/

[29]. Pile, S., ‘Community Engagement Project Launched’, BGIS https://gisbarbados.gov.bb/blog/community-engagement-project-launched/ accessed 19 April 2022

[30]. Pan-American Health Organization, ‘Youth Hangout’ https://www.paho.org/en/events/covid-19-youth-hangout-my-formula-how-do-you-feel accessed 19 April 2022

[31]. Calarco, D., ‘Youth Leadership in Crisis Response and Supporting Resilient Communities’, OECD https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ff8cb5e0-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/ff8cb5e0-en accessed 19 April 2022

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This brief was written by SSHAP Fellows (Stephanie Bishop and Juliana Corrêa). We wish to acknowledge expert input from others who contributed their insights to and provided documentation for this brief: Dr Lisa McClean Trotman, Social and Behavior Change Specialist, UNICEF; Andrea Titus, Senior Youth Commissioner, Ministry of Youth (Barbados); Dr Monica Villaça Gonçalves, Lecturer, University of Espírito Santo). Additional acknowledgements are also extended to Santiago Ripoll and Megan Schmidt-Sane (IDS).

CONTACT

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Olivia Tulloch ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and Wellcome Trust Grant Number 219169/Z/19/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of IDS, Anthrologica or LSHTM.

KEEP IN TOUCH

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Bishop, S. and Corrêa, J. (2022) Key Considerations: Engaging Young People in Latin American and the Caribbean in the COVID-19 Response. Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) DOI: 10.19088/SSHAP.2022.017

Published July 2022

© Institute of Development Studies 2022

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode