On 6 February 2023, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale brought destruction to southern Türkiye and northern Syria. The official death toll exceeded 50,000, with more than 7,000 fatalities occurring in Syria.1 An estimated 12 million people were affected by the earthquake in total.2 While international aid from the UN and member countries started reaching government-held areas in Syria soon after the earthquake struck, equitable access to humanitarian assistance faced multiple barriers. International support to areas not controlled by the government was markedly delayed, with the first UN delegation arriving on the fifth day after the earthquake.

Despite this, several good practices were documented in the local response in Northwest Syria. Equipped with over 12 years of experience in a chronic conflict, many Syrian non-governmental organisations (NGO) and grassroots organisations were quick to respond, forming new alliances and consortia. If these were developed further to cover a variety of local actors, they could act as a vehicle for international aid. Such a model would enable sustainable interventions to address the impact of the earthquake and long-term vulnerabilities, increasing community resilience.

This brief examines the humanitarian response to the earthquake in Syria – specifically in the health sector – with the aim of identifying best practices, highlighting gaps and exploring new approaches to strengthen the response. It draws on academic and grey literature, including reports from leading NGOs and government agencies. The evidence is backed up by consultations and informal conversations held with stakeholders involved in the earthquake response in Syria. The brief was requested by SSHAP and was written by Dr Abdulkarim Ekzayez (King’s College London), with support from Diane Duclos (the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) and Soha Karam (Anthrologica).

Key considerations

Earthquake response and recovery in a chronic conflict

- Incorporate a detailed understanding of how multiple sources of vulnerability impact people’s ability to cope following an earthquake. The earthquake exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities associated with over a decade of conflict and weakened community resilience.

- Consider immediate, mid- and long-term consequences in response and recovery planning. This approach helps identify issues of chronic violence and injustices, ensuring response and recovery activities cannot be used to disempower or justify inequalities.

- Advocate for sustainable cross-border access to opposition-held areas in northwest Syria. This is required to ensure humanitarian access across all parts of Syria, taking account of territorial fragmentation with different areas of power and compromised crossline access.

- Avoid overattributing shortcomings in the earthquake response to sanctions. All sanctions regimes have clear exemptions for humanitarian activities. Sanctions were also temporarily lifted to facilitate the earthquake response.

- Recognise how unequal and politically driven humanitarian responses to the earthquake in Syria have further marginalised already vulnerable populations.

Local response

- Recognise and strengthen community-led responses in the first phase of an emergency. This can be done through collaborating closely with grassroots organisations and technical bodies with quasi-governmental roles (which fill gaps ordinarily covered by government), such as the White Helmets.

- Adopt a conflict-sensitive international response. Supporting local leadership of grassroots and diaspora organisations promotes sustainable recovery and avoids exacerbating the conflict through empowering involved parties.

- Invest in conflict-sensitive emergency preparedness. To date, Syria preparedness programmes have not been prioritised by donors and authorities. Identifying, strengthening and scaling-up disaster risk reduction measures is required to foster greater community resilience.

- Engage with Syrian diaspora organisations to enhance the impact of the response. Syrian organisations in the region and globally have significant technical and organisational experience, enabling them to play an important role in the earthquake response.

- Provide funding and support to technical bodies. Entities in opposition-held areas that fulfil roles traditionally covered by government, such as the White Helmets and the Health Directorates, provide a lifeline to affected communities.

UN response

- Re-evaluate accountability of the UN in the earthquake response. This is needed to ensure an equitable distribution of resources based on humanitarian needs rather than political considerations.

- Increase the involvement of humanitarian donors and international NGOs in guiding the response. This will help counter the possible limitations of UN leadership due to political and operational restrictions.

Sustainable emergency response

- Establish consortia with functional structures that leverage the advantages of involved actors. Local consortia of humanitarian actors could include: Syrian diaspora organisations to foster international collaboration, regional Syrian NGOs to handle logistics, bodies with quasi-governmental roles to coordinate field implementation, and grassroots organisations to engage communities.

Background and context

The conflict in Syria is complex. It began in 2011 with civil protests demanding greater freedoms and political participation, inspired by the Arab Spring. These demonstrations were met with a violent response from the Assad regime, leading to a full-scale armed conflict. This conflict has caused immense suffering for Syrians, with over 875,000 fatalities,3 and almost half of the 21 million pre-conflict population have been displaced.4 Humanitarian consequences have been severe. Critical infrastructure, including healthcare facilities, has been destroyed, hindering access to basic services. As of February 2023, Physicians for Human Rights had documented 601 attacks on 400 healthcare facilities and the killing of 942 medical personnel, mostly by the Government of Syria (GoS) and its allies.5 Immense suffering has also been caused by the GoS’ targeting of urban areas with chemical and other crude weapons such as barrel bombs.6

Since the fall of the Islamic State in 2018, there have been three distinct areas of control. Approximately 60% of the country – including Damascus and the majority of the central, coastal and southern parts – is governed by GoS; northeast Syria and northern Euphrates (population approximately 3 million) is ruled by the Kurdish-majority Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, with support from the US, and the remaining 15% of the country in the northwest (population approximately 4.5 million) is controlled by the Islamic Group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, and other opposition groups backed by Türkiye.7 For a colour-coded map of the areas of control, see JUSOOR’s Map of Military Control Across Syria at the End of 2022 and the Beginning of 2023.

Attempts to resolve the conflict have been ongoing, with multiple rounds of peace talks and international negotiations. However, a lasting solution is yet to be reached. The forecast for the Syrian conflict in the coming years is uncertain and the current state of affairs, with distinct territories controlled by different groups, may persist for the foreseeable future.

Each territory has implemented its own unique adaptation strategy to address the conflict and develop local governance to deliver essential services. The health system in opposition-held areas collapsed in the early days of the conflict with the withdrawal of the Ministry of Health. In response, local medical networks developed a bottom-up approach to construct a hybrid health system, acting as an independent local health authority. For example, the Idlib Health Directorate has maintained its role as the technical health authority in Idlib without formal affiliations with either of the local governments in the region (the Interim Syrian government based in Türkiye, or the Salvation Government linked with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham). Military actors have avoided interfering with this health system, implicitly recognising it as an irreplaceable framework.8

Box 1. UN humanitarian access modalities

Cross-border modality refers to providing humanitarian assistance across international borders, often without the approval of the receiving state. This type of access is often used in situations of conflict or disaster where it is difficult to negotiate permission with the government of the receiving country.

Crossline modality refers to providing humanitarian assistance within a country, crossing the conflict contact lines but with the permission of the state. This type of access is used in armed conflict when the government of the receiving country does not control all territories and the main humanitarian response is based within the country.

Humanitarian access faces major challenges in Syria due to safety and security concerns. Since the beginning of the conflict in 2011, local responders have constituted the mainstay of the humanitarian health response. International NGOs have partnered with local NGOs to deliver assistance, requiring the development of new approaches to partnership, capacity-building activities and remote monitoring.9 In 2014, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 2165, allowing UN agencies and their partners to deliver cross-border aid to: northwest Syria via the Turkish border, northeast Syria through the Iraqi border, and southern Syria via the Jordanian border.10 The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) established cluster systems in each area or ‘hub’. However, the resolution had to be extended annually, and cross-border access to northeast and southern Syria expired in 2019 due to Russia exercising its power to veto this resolution. This left a single accessible crossing point at Bab al-Hawa into northwest Syria. Consequently, at the time of writing there are three UN-led humanitarian hubs focused on Syria: the Damascus hub serving government-held areas, with limited crossline activities into southern and northeast Syria; the Gaziantep hub in southern Türkiye for opposition-held areas in northwest Syria; and a Whole of Syria hub in Amman to coordinate the response nationally. See Box 1 for a definition of the two main modalities for delivering humanitarian aid in Syria.

Impact of the earthquake in Syria

The affected areas in northwest Syria included both government-held areas of Aleppo and Hama Governorates, and non-government-held territory in Idlib and Aleppo – where the majority of the destruction occurred. The earthquake caused more than 7,259 fatalities and over 12,000 injuries, destroyed over 5,000 homes and damaged more than 20,000 homes (White Helmets, personal communication, May 04, 2023).

The earthquake resulted in significant political, economic, and social effects. Most notably, it exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities that have deepened over the 12-year conflict. This is particularly noticeable in opposition-held areas, where internally displaced persons make up around 65% of the population.4 The earthquake also magnified divisions between the various factions involved in the conflict, with the Syrian government, opposition groups and the self-administered northeast Syria all vying for political gain from the response to the disaster. This has diverted the attention of the respective authorities away from the humanitarian consequences of the earthquake, leaving response tasks largely to civil society actors and humanitarian organisations.

Further, it has highlighted the lack of disaster risk reduction measures across the different areas of control. Despite some calls to initiate early recovery and sustainable humanitarian interventions with the reduced hostilities since 2020, the earthquake has demonstrated that little progress has been made in this regard; most humanitarian actors lack effective strategies to increase community resilience and develop preparedness plans.11

Impact in government-held areas

Government-held areas in northwest Syria that were affected by the earthquake include parts of Aleppo, Hama, and Lattakia, where approximately 5.2 million people were impacted. The immediate consequences of the earthquake included fatalities, injuries and displacement as well as pressure on health facilities, food and shelter. The internal displacement of communities has been of significant concern, with many people forced to seek refuge in other neighbourhoods or areas of the country. The conflict has had an adverse effect on societal ties and structures within these areas, contributing to the psychological impact of the earthquake.12 Furthermore, many people were left without access to basic necessities such as food, water and shelter. The situation was compounded by the chronic poverty Syrians face as a result of the conflict, with more than 90% of Syrians living below the poverty line.13

The earthquake put pressure on the country’s already weakened healthcare system, which struggled to cope with the number of injuries and fatalities, particularly in the first two days until the international convoys arrived. However, when they did arrive international convoys helped to alleviate the immediate burden on the local health system. There was a major gap in mental health service coverage due to the limited number of specialised health personnel. The fragile infrastructure in areas that have witnessed heavy bombardment and airstrikes throughout the conflict was easily destroyed by the earthquake, and shelter needs spiked due to the displacement of communities.

Overcrowded camps and collective shelters lacked the minimum standards for living, including the provision of safe water. Water pipelines and supplies in Aleppo were damaged either directly by the earthquake or from the increased burden on the water networks following displacement, further deteriorating infrastructure that had already been weakened by the conflict. Data shows that only 50% of water and sanitation networks in Syria are currently functioning.14 The earthquake could further increase the risk of public health threats, such as cholera, which has been present in Syria since August 2022 and caused 104 deaths between August 2022 and April 2023.15

The earthquake could lead to the long-term displacement of communities, disrupting social structures, causing livelihood losses and heightening vulnerability. This could have lasting effects on communities, including the loss of social networks, disrupted education and limited access to healthcare. The destruction of infrastructure and homes has also led to significant livelihood losses for many people, further entrenching poverty and economic hardship.

Impact in opposition-held areas

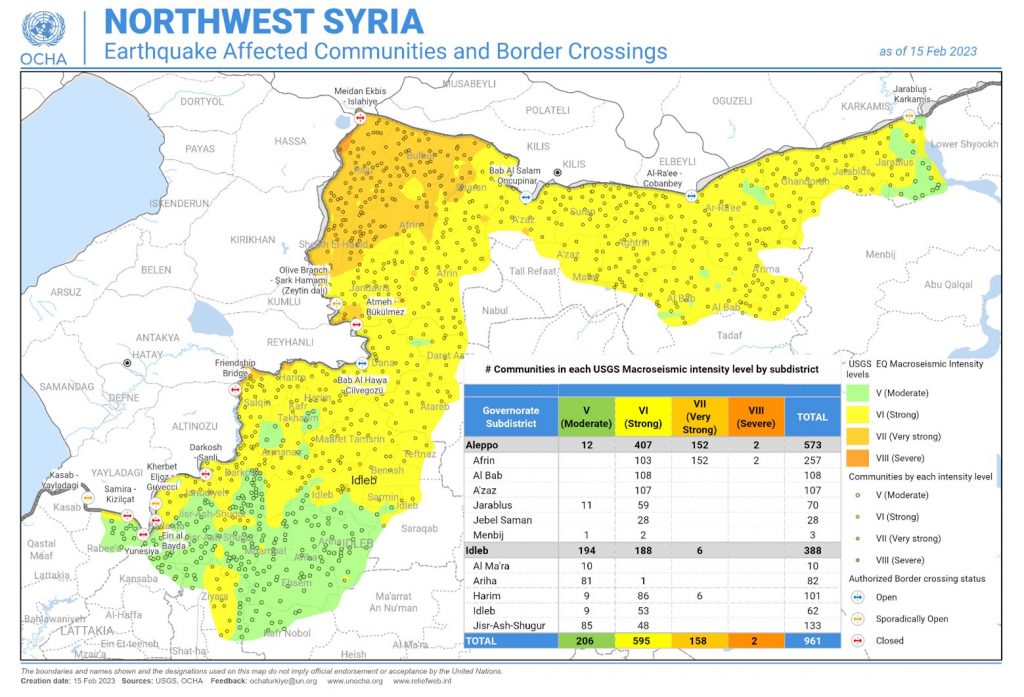

Opposition-held areas in northwest Syria impacted by the earthquake include parts of Idlib and Aleppo, with an estimated 4.5 million people affected.16 See Figure 1 for an illustration of the communities and border-crossings affected by the earthquake.

| Figure 1. Areas affected by the earthquake as of 15 Feb 2023 |

|

Source: USGS, OCHA: Syrian Arab Republic | OCHA (unocha.org).

As the last stronghold of the opposition, these areas were most affected, given their vicinity to the Turkish border and epicentre of the earthquake. Sixty-five percent of the population in these areas had been displaced from other parts of Syria. Women, children, people with disabilities and the elderly are particularly vulnerable, with 1.4 million living in tented settlements and facing freezing temperatures prior to the disaster.17 Access to the area was largely limited to cross-border aid via the Bab al-Hawa border-crossing.

The earthquake had a significant social impact on these areas. Two districts – Harem and Afrin – were hardest hit, resulting in waves of displacement to already-crowded districts in the region. It has been reported that some 53,000 families were displaced and in need of shelter.16 Security incidents also represented a major challenge; 11 days after the earthquake, GoS targeted opposition-held areas in northwest Syria with airstrikes, attacking the city of Atareb and surrounding areas.

The earthquake further strained limited resources and overwhelmed the already fragile health system in opposition-held areas; an estimated 55 health facilities were totally or partially damaged. This meant the immediate health needs of the population could not be adequately met. This was particularly true for traumatic injuries, including crush injuries and resulting renal failure.18 The mental health needs of the population and first responders was vast, especially since lives could have been saved if resources had arrived sooner. The referral of patients to Türkiye for healthcare services that are not available in the region, such as cancer treatment, was suspended following the earthquake due to the extreme burden on the health system in southern Türkiye. As a result, those affected sometimes faced insurmountable barriers when seeking healthcare.

Emergency aid to northwest Syria was delayed, with limited search and rescue equipment and supplies arriving in the immediate aftermath, when the likelihood of finding survivors was highest. The delay likely contributed to preventable morbidity and mortality of an already vulnerable population. The earthquake also disrupted food supplies and access to clean water, further exacerbating humanitarian needs.19 Similarly to the potential long-term impact of the earthquake in government-held areas, displacement and disruption to social structures, livelihood losses, and heightened vulnerability are also expected in opposition-held areas. However, with a lack of central state and national planning in the region and minimal international support, these vulnerabilities could have even greater long-term consequences in opposition-held areas.

Most communities in this region rely on agriculture as their main source of income. The latest military offensive in the region in 2019 and early 2020 resulted in GoS taking over large areas in southern Idlib and displacing about 1.2 million people. Since then, these populations have lost access to the fertile agricultural lands in northern Hama and southern Idlib, becoming dependent on other communities and on humanitarian aid.

Community resilience in this region is at a very critical stage and could be further weakened in the aftermath of the earthquake. Local resources have been stretched to the limit, with most families becoming dependent on foreign aid. Before the earthquake, the food crisis was rapidly worsening and affecting communities dependent on humanitarian aid.20 The sectors of water, sanitation and hygiene; education; protection, and gender were likewise facing significant shortages, due to a decline in humanitarian funding. The earthquake will likely further weaken all local systems in the region, impacting the health system’s ability to meet the need for routine clinical care, which remains high due to the protracted conflict in Syria.

Humanitarian response dynamics

The humanitarian response and earthquake relief efforts in government- and opposition-held areas of Syria were varied due to political dynamics, access restrictions and differing levels of international assistance. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, local responses in both areas were essential to meet the urgent needs of affected populations. The Syrian people responded to the disaster by organising individual and civil initiatives to fill the gaps in search and rescue, first aid and relief operations. Local associations and individuals collected and distributed food, drinking water, sanitary materials, blankets, and mattresses received through donations from inside the country and abroad. The arrival of external assistance boosted ongoing relief efforts in both government- and opposition-held areas.

Despite this, response efforts in both areas were hindered by the political situation in Syria which impeded access and exacerbated difficulties in coordinating relief operations. In government-held areas, the ongoing conflict and security concerns led to restricted access to some of the affected areas. The absence of formal recognition of opposition-held areas by the international community, combined with the ongoing conflict, also created barriers to accessing and delivering aid to affected communities in opposition-held areas.

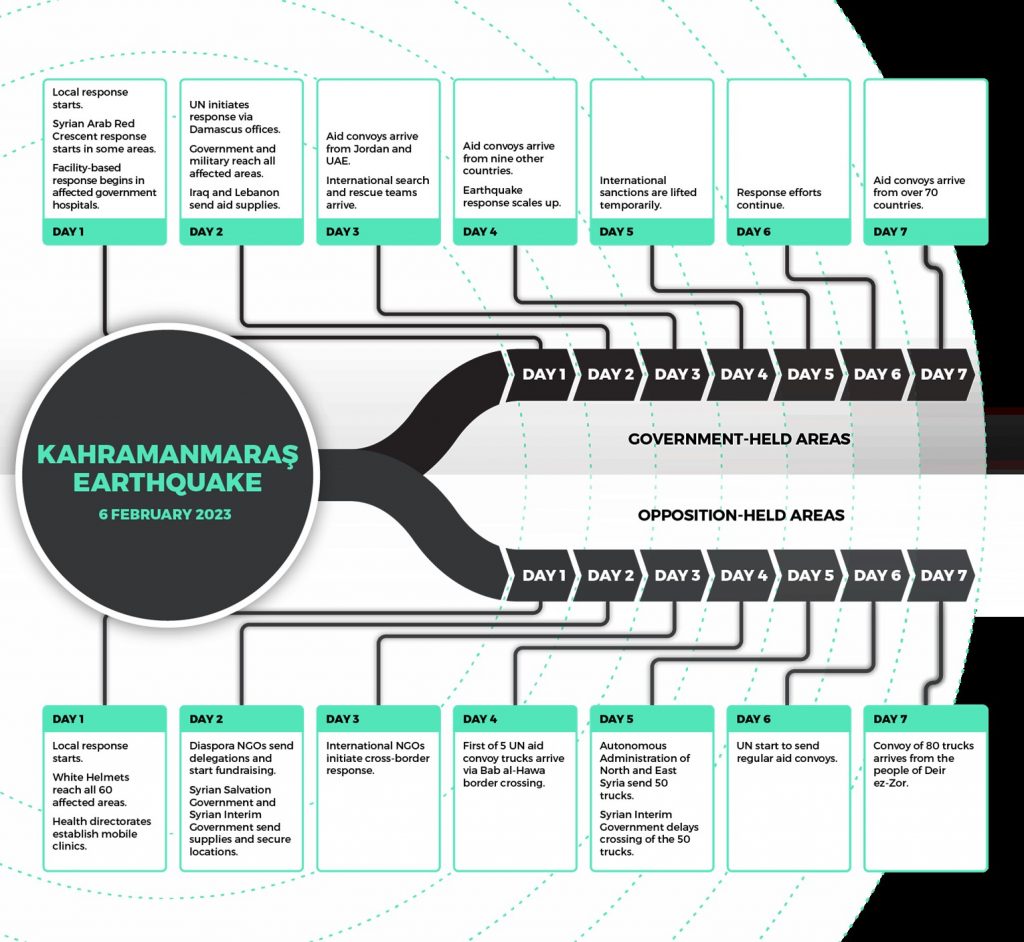

| Figure 2. Timeline of early response activities in government- and opposition-held areas |

|

Source: Author’s own.

The contrast in the humanitarian response and earthquake relief efforts in government- and opposition-held areas of Syria reveals the challenges in responding to crises in conflict-affected settings. Political elements and access restrictions have a significant effect on the capability of local and international organisations to provide aid to affected populations. Nevertheless, the resilience and resourcefulness of local organisations in the early stages of the crisis demonstrates the importance of community-led responses and the need for continued support to and investment in these organisations.

Response dynamics in government-held areas

In the aftermath of the earthquake, swift search and rescue operations were undertaken by local people, the military, and first responders. The government declared a state of emergency and international aid agencies were mobilised to support response efforts. Key players included the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and relevant Syrian government agencies, such as the Civil Defence, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Social Affairs. These entities led and coordinated the initial relief operations, with hundreds of local and international humanitarian organisations providing emergency shelter, food, and medical assistance to affected communities. In addition, local communities and civil society groups played a key role, with volunteers evacuating the injured and providing support to displaced families.

Humanitarian access to affected areas was initially restricted due to security concerns and infrastructure damage. The government worked to improve access by clearing roads and coordinating with aid agencies to ensure safe passage. However, limited resources and capacity hindered the response. International organisations such as the UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross provided additional assistance, including tents, shelter kits, and medical supplies. Temporary collective shelters were established to house affected communities. Due to chronic shelter needs, however, it was difficult to differentiate between those who had lost their homes due to the earthquake and those who were already displaced prior to the earthquake. The quality of the collective centres and caravans was much higher than the tents in opposition-held areas in Idlib and Aleppo Governorates.

International sanctions were an important dynamic in the response within government-held areas, with GoS overattributing them for its inadequate response. However, international sanctions on Syria excluded humanitarian assistance and emergency response, with the US, UK, and EU sanctions temporarily lifted to allow more international support to be channelled to Damascus. The Syrian government had not prioritised emergency and disaster response prior to the earthquake and lacked a national fund for disasters. This contributed to the lack of preparedness and undermined public trust in the government’s ability to protect citizens. In response, the government approved the creation of a ‘Fund for the rehabilitation of affected areas’ (Governmental agency in Damascus, personal communication, May 05, 2023), however this has yet to materialise, and it is unlikely that the government will appropriately compensate people for damaged homes or help with the cost of restoration. Additionally, it was difficult to differentiate between earthquake damage and damage caused by other sources, such as airstrikes, due to a lack of pre-existing data. Reports of the military and security forces being heavily involved in relief efforts raised concerns over transparency and the politicisation of aid distribution. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights stated that it took two days for government aid to reach some of the affected areas. This highlights the government’s central role in the response, yet suggests that it was not always acting in the best interests of the affected populations.21

Response dynamics in opposition-held areas

The earthquake also triggered an immediate response from local responders and grassroots organisations in opposition-held areas. The Syrian Civil Defence, also known as the White Helmets, were the first to respond, mobilising their 3,100 volunteers who reached 60 affected sites within 10 hours of the earthquake to search for survivors and provide first aid to the injured (White Helmets, personal communication, May 25, 2023). However, their efforts were impeded by a lack of adequate equipment and funding and made it difficult to rescue people trapped under the rubble.

Similarly, the Idlib Health Directorate deployed mobile clinics and emergency teams to the affected sites on the first day of the earthquake, and other local humanitarian organisations were able to deploy their field teams within two days. Despite their limited resources, these organisations demonstrated an impressive level of community mobilisation and responsiveness during the early stages of the crisis. The local community provided support to ensure search and rescue efforts could continue, donating fuel and vehicles without which actors such as the White Helmets would not have been able to reach all affected communities (White Helmets, personal communication, May 25, 2023). The opposition authorities were responsible for providing coordination and support to local organisations. Both the Interim Government and the Salvation Government directed significant resources to be used by the White Helmets. These governments and their affiliated armed groups also played a role in securing the affected sites to ensure safe humanitarian operations.

The humanitarian cross-border response, which previously acted as a lifeline for northwest Syria, was paralysed in the first two days after the earthquake. Most humanitarian organisations working through the southern Türkiye hub, including UN agencies, were severely affected by the earthquake with their offices damaged and their staff affected and displaced. The Bab al-Hawa border – the only crossing point functioning for cross-border aid before the earthquake – was closed for two days due to road damage and the impact of the earthquake on the Turkish administration. Syrian diaspora and national NGOs were pivotal in resourcing and facilitating the response, with medical and humanitarian missions arriving in the country from the third day of the response. Several international NGOs were able to mobilise resources as early as the third day of the response, according to interviews with local responders.

It is widely accepted that the UN failed to meet the needs of affected communities in opposition-held areas in northwest Syria in the initial stages of the response. This was publicly expressed by Martin Griffiths, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator at the UN.22 As highlighted in Figure 2, an official UN delegation arrived in southern Türkiye and Damascus on the second day after the earthquake. However, it took them until the eighth day after the earthquake to visit opposition-held areas in northwest Syria.23 The first UN convoy, consisting of six trucks, arrived in northwest Syria on the third day after the earthquake (see Figure 2 above).17 This convoy was a scheduled shipment that was part of the cross-border humanitarian response and not a new convoy specific to the earthquake response. Since then, regular UN convoys have been arriving in northwest Syria to support the earthquake relief efforts. The shortcomings of the UN response may be partially attributed to the fact that the position of Deputy Regional Humanitarian Coordinator in Gaziantep has been vacant since late 2022. It can also be attributed to the suspension of one of the primary information-gathering mechanisms, the Humanitarian Needs and Assessment Programme, which had been led by the International Organization for Migration since January 2023. This was due to a lack of funding and caused a dearth of information during the response to the earthquake.

Due to the lack of formal international recognition of the opposition-held areas in northwest Syria, no state-backed foreign convoys or support were channelled to this area. Such foreign convoys ordinarily require international agreements between states. In the case of northwest Syria, there is no state that can initiate such an international request. Despite this, a few search and rescue and medical teams arrived from Egypt, Qatar, and the Syrian diaspora. These teams acted independently and did not represent their states.

In northwest Syria, humanitarian actors faced a significant challenge to reach people in need of assistance. Initially, GoS insisted that all aid for the region should go through Damascus. Following international pressure, however, they agreed to open two new border crossings for three months to allow more aid to be delivered. It was reported that this decision was made because of concerns that the UN Security Council might authorise a longer period.17 The military and civilian authorities in northwest Syria did not fully participate in search and rescue operations, demonstrating the weak governance and institutional fragility of opposition governments, which prioritised security above all else. The Syrian Interim Government temporarily suspended aid from the northeast, which is under Kurdish control, purportedly until receiving clearance from Türkiye.24

Considering the lack of international recognition and community acceptance for local governments in northwest Syria, organisations with quasi-governmental roles, such as the White Helmets and the Health Directorates of Idlib and Aleppo, formed a key part of the response. Significant contributions were also made by Syrian NGOs. These technical bodies are not formally affiliated with political governments, enabling them to operate with greater neutrality. They also have high community acceptance, as they work alongside communities using ground-up approaches.

Conflict-sensitive and long-term recovery

The devastating earthquake of February 2023 highlighted the need for a conflict-sensitive and long-term recovery process that takes into account pre-earthquake vulnerabilities and supports the resilience of communities. To this end, earthquake response should focus on identifying and scaling up best practices.

Investing in emergency preparedness

The strong community engagement and mobilisation that was seen can be bolstered through a conflict-sensitive international response that supports local leadership and promotes sustainable recovery. In addition to strengthening and integrating risk reduction measures and increasing community resilience, emergency programmes must focus efforts on emergency preparedness. This could include assessing the structural readiness of schools and homes of people with disabilities to reduce the impact of disasters.11 It is essential that aid is delivered through direct engagement with local humanitarian organisations and quasi-governmental structures – as was the case of northwest Syria – and that this is done in a way that strengthens local systems and paves the way for sustainable recovery.

A model for sustainable recovery

A model to engage with local actors in a conflict-sensitive manner should be further developed to enhance local leadership in the response. This model could draw on the formation of local consortia of humanitarian actors, consisting of diaspora Syrian organisations, regional Syrian humanitarian NGOs, bodies that have quasi-governmental roles with technical expertise, and grassroots organisations. Involving a diverse range of actors, and recognising the complementary value they each bring, is vital to fostering a locally led response. Such an approach helps ensure that communities’ priorities are understood and actioned, that humanitarian principles are upheld, and that the quality of services is improved.

These consortia could have functional structures that leverage the advantages of each actor. Whereas diaspora organisations can foster international collaborations and engage with external donors, regional humanitarian NGOs can handle logistics and payment channels. Likewise, bodies that have quasi-governmental roles can coordinate field implementation, while grassroots organisations can engage with communities and mobilise local resources. A model such as this could enable sustainable interventions that effectively address the impacts of the earthquake and long-term vulnerabilities, thereby increasing community resilience.

The feasibility of implementing such a model has been explored through initial discussions with donors, including the US Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), and with practitioners, including the White Helmets and a number of diaspora organisations. The model could consider different modalities of funding and implementation to ensure a locally led response and sustainable recovery.

As part of this brief, a series of discussions and meetings were held with various actors including from diaspora organisations, coordination platforms and local grassroot actors. As a result, the Syrian American Medical Society, the White Helmets and the Syrian Forum established the first consortium to contribute to the earthquake response in northwest Syria to illustrate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed model. The consortium has developed a response plan for the earthquake that seeks to bridge the gap between emergency relief efforts and long-term recovery needs. However, the scope of this plan is bound to the specific expertise and capacity of the actors that currently form this consortium.

Next steps to formalise this model include further consultations with donors and practitioners, and the formation of partnerships with local organisations active across a wide range of sectors, such as farmers’ associations, women’s groups, and schools. Additional ways of engaging with affected communities should be sought and should purposively engage vulnerable groups that have been marginalised by the conflict. It will be also important to engage with external donors and organisations to mobilise funding to properly resource the model. A communications strategy and mechanism for information-sharing between the relevant actors is also necessary. Finally, the model should uphold the values of transparency and accountability, with routine monitoring and assessment of outcomes.

Conclusion

Humanitarian response in any given context provides a lens through which to understand underlying power dynamics and structural inequalities, such as the disproportionate impact on the most vulnerable in northwest Syria. Comparative responses to similar natural disasters, such as the earthquake response in Türkiye, or the conflict response in Ukraine, illustrate the political and economic disparities at play. The response in Syria has worked to reinforce the marginalisation of already vulnerable populations, serving as a reminder of how politically driven resource allocation often comes at the expense of human lives and dignity.

It is imperative that lessons from the earthquake response are applied to consider both immediate- and long-term needs. To address the urgent humanitarian and health needs of the population – the scale of which remains vast – more funding and resources are needed for local search and rescue teams, as well as for responders providing health, water sanitation and hygiene, shelter, and protection assistance. The diversion of aid to parties of the conflict should be prevented and cross-border access must be ensured. Stronger commitment to this approach by UN leadership and the wider humanitarian community is required and action must be taken to ensure that aid is reaching those who need it most. Where the UN system falls short, concerned governments can work together to establish alternative, effective mechanisms to deliver cross-border aid. Ultimately, in the context of responding to a natural disaster or sudden on-set emergency in Syria, pervasive instability must be overcome. Political solutions to the conflict must be urgently sought in order to minimise levels of humanitarian need in the event of another natural disaster or emergency event in the area.

Acknowledgements

This brief was written by Abdulkarim Ekzayez (King’s College London) with support from Diane Duclos (the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine – LSHTM) and Soha Karam (Anthrologica). Contributions and reviews were made by colleagues at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Anthrologica, the White Helmets, Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), Syria Public Health Network, Shafak Syria, and volunteers involved in the response. The brief was edited by Georgina Roche (the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP) editorial team). The brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

Contact

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Juliet Bedford ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica , CRCF Senegal, Gulu University, Le Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, University of Ibadan, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

Keep in touch

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Ekzayez, A. (2023). Key Considerations: Humanitarian Response to the Kahramanmaraş Earthquake in Syria. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP) http://www.doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2023.018

Published June 2023

© Institute of Development Studies 2023

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode

References

- British Red Cross. (n.d.). The latest news on the earthquakes in Türkiye (Turkey) and Syria. British Red Cross. Retrieved June 22, 2023, from https://www.redcross.org.uk/stories/disasters-and-emergencies/world/turkey-syria-earthquake

- Bayraktar, D. M. (2023). Socio-economic Risks of Groundwater Vulnerability, Contamination & Earthquakes: Revisiting The Izmit (1999) and Kahramanmaras (2023) Earthquakes in Turkiye (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4400117). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4400117

- Alhiraki, O. A., Fahham, O., Dubies, H. A., Hatab, J. A., & Ba’Ath, M. E. (2022). Conflict-related excess mortality and disability in Northwest Syria. BMJ Global Health, 7(5), e008624. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2022-008624

- Abbara, A., Rayes, D., Ekzayez, A., Jabbour, S., Marzouk, M., Alnahhas, H., Basha, S., Katurji, Z., Sullivan, R., & Fouad, F. M. (2022). The health of internally displaced people in Syria: Are current systems fit for purpose? Journal of Migration and Health, 6, 100126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100126

- Physicians for Human Rights. (2022). A Map of Attacks on Health Care in Syria. Physicians for Human Rights. https://syriamap.phr.org/#/en

- Ekzayez, A., & Sabouni, A. (2020). Targeting Healthcare in Syria. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 2(2), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.7227/jha.038

- Zulfiqar, A. (2020). Syria: Who’s in control of Idlib? – BBC News. BBC Reality Check. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-45401474

- Ekzayez, A. (2018). Analysis: A Model For Rebuilding Infrastructure in—Peacebuilding Deeply. Syria Deeply.

- Duclos, D., Ekzayez, A., Ghaddar, F., Checchi, F., & Blanchet, K. (2019). Localisation and cross-border assistance to deliver humanitarian health services in North-West Syria: A qualitative inquiry for the Lancet-AUB Commission on Syria. Conflict and Health, 13(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0207-z

- Security Council Resolution 2165 (2014). UNSCR doc S/RES/2165. http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/2165

- Schuler-McCoin, H. (2023, April 24). The next steps for disaster risk reduction in Syria. The New Humanitarian. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2023/04/24/earthquakes-could-spark-progress-disaster-risk-reduction-syria

- Soqia, J., Ghareeb, A., Hadakie, R., Alsamara, K., Forbes, D., Jawich, K., Al-Homsi, A., & Kakaje, A. (2023). The Mental Health Impact of 2023 Earthquake on the Syrian Population: A Heavy Mental Health Toll (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4423481). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4423481

- UN. (2022). As Plight of Syrians Worsens, Hunger Reaches Record High, International Community Must Fully Commit to Ending Decade-Old War, Secretary-General Tells General Assembly | UN Press. https://press.un.org/en/2021/sgsm20664.doc.htm

- ICRC. (2023). After earthquake damage in northwest Syria, urgent action needed to prevent collapse of water systems and avoid devastating humanitarian consequences (Middle East/Syria;Europe and Central Asia/Türkiye) [News release]. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/after-earthquake-damage-northwest-syria-urgent-action-needed

- OCHA, UNICEF, & WHO. (2023). Whole of Syria Cholera Outbreak Situation Report no. 16 Issued 08 May 2023. https://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/syria/Cholera-Sitrep_8_april_2023.pdf

- OCHA. (2023). North-west Syria: Situation Report (28 April 2023). https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/syria/

- Jabbour, S., Abbara, A., Ekzayez, A., Fouad, F. M., Katoub, M., & Nasser, R. (2023). The catastrophic response to the earthquake in Syria: The need for corrective actions and accountability. Lancet (London, England), 401(10379), 802–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00440-3

- Alkhalil, M., Ekzayez, A., Rayes, D., & Abbara, A. (2023). Inequitable access to aid after the devastating earthquake in Syria. The Lancet Global Health, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00132-8

- OCHA. (2023). Earthquakes: North-west Syria: Flash Update No. 6 As of 12 February 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/earthquakes-north-west-syria-flash-update-no-6-12-february-2023

- Adleh, F., & Duclos, D. (2022). Key Considerations: Supporting ‘Wheat-to-Bread’ Systems in Fragmented Syria. SSHAP. https://doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2022.027

- Daher, J. (2023). The aftermath of earthquakes in Syria: The regime’s political instrumentalisation of a crisis [Technical Report]. Europeen University Institute. https://doi.org/10.2870/167974

- Martin Griffiths [@UNReliefChief]. (2023, February 12). At the #Türkiye-#Syria border today. We have so far failed the people in north-west Syria. They rightly feel abandoned. Looking for international help that hasn’t arrived. My duty and our obligation is to correct this failure as fast as we can. That’s my focus now. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/UNReliefChief/status/1624701773557469184

- Human Rights Watch. (2023). Northwest Syria: Aid Delays Deadly for Quake Survivors. Human Rigths Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/15/northwest-syria-aid-delays-deadly-quake-survivors

- Amnesty International. (2023). Vital earthquake aid blocked or diverted in Aleppo’s desperate hour of need. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/03/syria-vital-earthquake-aid-blocked-or-diverted-in-aleppos-desperate-hour-of-need/