Mpox has spread along the Busia-Malaba border that links eastern Uganda and western Kenya, with risk factors centred on cross-border mobility. Community responses to mpox are shaped by access to information on radio, television and social media as well as local terminologies, understandings of disease aetiology, spiritual and religious beliefs, household structures and cross-border mobility patterns. Despite vaccine allocations from the World Health Organization (WHO), the response has been hindered by resource constraints, mistrust and cross-border challenges. This brief summarises findings on how mpox is perceived and managed in the Busia-Malaba border region. It draws on a rapid review of qualitative data, local media, non-governmental organisation (NGO) and academic reports, and cultural histories based on long-term research in the region.

Key considerations

- Frequent alerts to prevent the cross-border spread of disease have resulted in local fatigue with disease control measures. The high volume of daily cross-border traffic (over 2,000 trucks and thousands of traders and families) has produced frequent disease alerts in recent years. The volume of disease alerts has bred ‘alert fatigue’, leading people to view fresh control measures as burdensome and, in some cases, to sidestep them altogether.

- There is no widely used local term for mpox in the border region. In multiple local dialects, language surrounding mpox is often conflated with chickenpox or recalls smallpox (terms include Ndui, Namusuna, Kawaali and Ekodoi).

- Formal care is often deferred until symptoms become severe. People combine biomedical, herbal and religious treatments. Cost, distance and socio-cultural beliefs inform decision-making. Calamine lotion and herbal infusions (e.g., neem, Cleome gynandra) are cheap, accessible and often used as first-line treatments.

- Traditional healers outnumber biomedical providers in many rural areas and are often the first line of care for those exhibiting mpox-like symptoms. Faith healing (particularly in Pentecostal and syncretic churches) is also influential. Some religious communities may flout official directives but can be important partners if engaged constructively.

- Stigma evoked by mpox lesions can reduce reporting and care-seeking, promoting underdiagnosis and ongoing spread. Families may hide cases, fearing social rejection, lost income or moral scrutiny, recalling similar patterns in the early years of HIV/AIDS.

- Discourses of ‘high-risk groups’ can exclude broader populations who are at risk from mpox. Truck drivers and sex workers have been particularly singled out as high-risk groups for the transmission of mpox. While focus on the needs of these groups is essential, mpox in the border region has already spread beyond these groups.

- Household structures and care responsibilities may increase close-contact caregiving, while cost and stigma are barriers to providing safe care. Extended families (often multigenerational, sometimes polygamous) increase close-contact caregiving. Poverty and crowded living conditions make safe caregiving more challenging. Women and older daughters typically provide bodily care, and using protective gloves can be seen as ‘unloving’. Cost and stigma are further barriers to safely managing infected relatives.

- There remain important gaps in systematic and up-to-date information on mpox transmission and response. Data are needed on the effectiveness of existing community health structures, behavioural economics of care, community perceptions of caregiving risks, evolving role of traditional healers, mobility patterns and identification of emergent beliefs.

Regional context

Overview of mpox cases and responses

Clade Ib monkeypox virus (MPXV), a strain of the virus that causes mpox and is known for its high transmissibility, has spread from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) into Uganda and Kenya. Mpox gained attention in the Busia-Malaba border region in 2024 when an infected long-distance truck driver was diagnosed in Malaba.1 Responses to mpox have been hampered by logistical challenges, funding cuts (following the January 2025 Stop Work Order for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)) and regional conflict in eastern DRC. Uganda began mpox vaccinations on 1 February 2025, while Kenya’s mpox vaccination campaign remains pending as of April 2025.2 After an initial burst of social media and NGO attention, mpox has slipped from the headlines and aid agendas. At the local level, mpox is not a priority concern; awareness of the risks of mpox may be reduced or underplayed, and cases may go undetected.

Geographic overview

The Busia-Malaba region contains two primary border crossing points (Busia and Malaba), as well as over 200 documented informal footpaths (figures from 2023).3 The region is a site of intensive trading, frequent cross-border visits for healthcare or family reasons, and deeply intertwined kinship ties. Over 2,000 trucks cross the border daily at One Stop Border Posts. With traffic from across southern, central and eastern Africa, the border region experiences frequent public health alerts (most recently for Ebola disease), prompting regional coordination to limit cross-border spread.

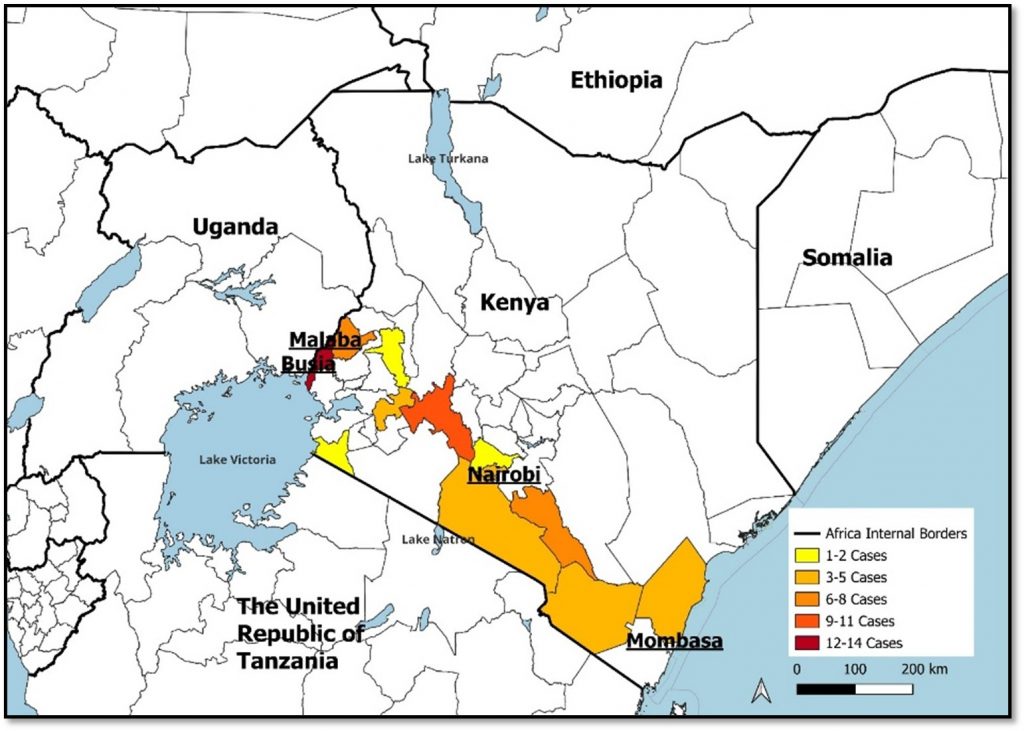

Figure 1. Distribution of confirmed mpox cases in Kenya, 2024 to 2025

Source: Prepared by Hugh Lamarque using the following map and data. Map: UNHCR – The UN Refugee Agency. (2025). Second-level administrative divisions (admin2) [Dataset]. The Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX). https://data.humdata.org/dataset/second-level-administrative-divisions-admin2. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Data: From Mpox Situation Report, 4 April 2025, Kenyan Ministry of Health PHEOC.

Ethnic and linguistic composition

The primary ethnic groups along the border include Samia (Luhya subgroup), Teso (Iteso), Basoga and Banyole, alongside Japadhola, Luo and others. In Busia, Swahili and English languages dominate formal and informal trade, health services and schooling, while disease concepts remain grounded in local languages. Dialects of Luhya (Lusamia and Olunyole), Ateso, Lusoga, Luganda and Japadhola (Dhopadhola) coexist. Communities frequently straddle both countries, sustaining shared culture and dense cross-border social and familial networks.4 These long-standing transboundary networks heighten transmission risk while also offering key entry points for coordinated surveillance and culturally attuned health messaging.

Health-seeking landscapes

Biomedical healthcare infrastructure around Busia and Malaba

Kenyan health facilities include Busia County Referral Hospital, Alupe Sub County Referral Hospital, Kocholya Sub County Hospital and numerous smaller dispensaries and private clinics. On Uganda’s side, the main facilities are Busia District Hospital, Masafu General Hospital and local clinics. People in both countries cross the border to access formal healthcare, with a study from 2021 reporting that 30% of sampled residents on both sides of the border had recently crossed the border for this reason.5 The Kenya Ministry of Health has added a new signal for mpox detection as well as event-based surveillance. However, a number of recent studies have shown waning attention to infection prevention and control measures since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.6 Inadequate infection prevention and control, and inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities are likely to exacerbate the spread of mpox. Since January 2025, the sudden withdrawal of USAID funding in the region has significantly reduced the capacity of health systems. Many NGOs have turned away from mpox to issues considered more pressing concerns, such as gaps in HIV/AIDS care and in the delivery of essential care.

Disease terminologies

Many communities lack Indigenous vocabulary for mpox. Some emerging names refer to chickenpox or recall smallpox. Relevant linguistic terms are shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Linguistic terms relevant for mpox in the Busia-Malaba border region

| · Ndui (Swahili): smallpox

· Tetekuanga (Swahili): chickenpox · Nundu (Luo): smallpox, chickenpox · Ekodoi (Ateso): referencing pustular conditions akin to historical smallpox · Namusuna (Luganda/Lusoga): chickenpox, traditionally associated with smallpox · Kawaali (Luganda/Lusoga): traditionally associated with smallpox, used in Ugandan government documents to refer to mpox |

Source: Authors’ own.

Hybrid health-seeking practices

Hybrid health-seeking practices are common throughout the border region, with people moving between biomedical, traditional and religious forms of healing. Mpox is often confused with chickenpox, which is most often treated at home with herbal remedies or using calamine lotion.7 Common multipurpose herbal treatments include infusions (e.g., neem (mwarubaini)), which are either consumed or used in baths, and common medicinal plants, notably Cleome gynandra.8 The use of traditional medicine is more common among older individuals, married couples and those residing far from formal health facilities.9

Families often combine herbal remedies with partial engagement of formal clinics or pharmacies.10 Due to the cost of private health facilities, people will often seek treatment at home in the first instance and only attend a medical facility when symptoms are severe.11 Given their societal status, traditional medicine practitioners are important partners for delivering primary healthcare. Cross-border traditional healing networks are common, with Kenyan families seeking well-known herbalists in Uganda and vice versa.12 In the case of mpox, traditional medicine practitioners may risk infection by handling sores without protective measures. Many people employ differing explanatory models simultaneously, and it is common for people to explore concerns relating to witchcraft alongside the use of herbal and biomedical remedies, particularly when the onset of a disease is sudden or accompanied by visible signs and symptoms.13

Religious and faith healing

Healing activities are a central part of Pentecostal and syncretic churches. Pentecostal pastors and independent churches often hold ‘deliverance’ sessions with this purpose. Similarly, some Muslim communities rely on Hadith-based quarantine teachings. The HIV/AIDS epidemic revealed the complex and contradictory nature of churches across East Africa: religious groups frequently perpetuate stigma through moralistic discourse and by reinforcing conservative gender ideology, while also providing an important source of support for people who are sick and to quarantined households.14 During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were examples of religious communities flouting rules around community gatherings to hold religious services.15 However, religious communities can be important partners for the successful delivery of public health directives, such as wearing face masks, washing hands and social distancing.16

Stigma

Accounts from elsewhere in the region show how mpox lesions can prompt suspicion of moral wrongdoing (e.g., witchcraft or ‘unclean’ behaviour).17 Neighbours, food sellers and bodaboda motorbike taxi drivers may also refuse physical contact or avoid accepting money from caregivers, heightening the shame felt by afflicted families. The reluctance to reveal illness can foster under-reporting. During the HIV/AIDS epidemic, support from trusted friends or relatives, many of whom themselves had sought HIV testing and treatment, encouraged people with HIV to seek care.18 Mpox parallels are emerging, but at present it is unclear how these dimensions will unfold. It is also unclear what the effect of public health messaging and NGO activity will be, especially given that many NGOs have withdrawn from mpox work in recent months due to sudden funding constraints.

Sex workers and other ‘at-risk’ groups

As with the HIV/AIDS epidemic, key populations, especially female sex workers, have been identified as significant risk groups for mpox due to intimate contact between people with multiple sexual partners. Commercial and transactional sex is widely prevalent in border towns and other locations catering to truck drivers, another group deemed ‘at risk’. The ‘at-risk’ classification of these groups raises several issues. In communities where concurrent heterosexual partnerships are the norm (as in much of this region), many people who are at heightened risk of sexually transmitted infections may not take precautions if interventions are targeted primarily at at-risk groups. The category ‘sex worker’ does not always align with women’s own classification of their practices, meaning that potentially vulnerable people are not engaged through this approach.19 Male sex work tends to be obscured in dominant discourses about sex work in the region. Others have argued that a focus on ‘risk groups’ can inadvertently result in blaming those who are most vulnerable to mpox for its spread.20 The association of mpox with at-risk groups can heighten fears of social rejection, discrimination and stigma, creating additional barriers to disclosure, safe management and support for those infected.

Early in the mpox outbreak, many people conflated mpox with more familiar sexually transmitted infections. NGOs working with sex workers have advocated for targeted outreach and vaccination, noting that many sex workers have minimal financial means and cannot afford to stop working. While some sex workers hide symptoms, others practice informal screening (checking a client’s skin for suspicious sores), limiting potential exposures. Collaboration with local health clinics (often an extension of existing HIV outreach) has begun to include mpox testing and counselling for this marginalised population.

Households and caring dynamics

Households in the border areas typically include multiple generations and, in some cases, multiple wives.21 Decisions on healthcare within families often rest with men, particularly when a decision involves incurring expense to travel to a health facility. Women are responsible for caregiving tasks, especially bodily care. Women are more likely to have contact with lesions, scabs and/or bodily fluids through caregiving. They are also more likely to have contact with contaminated clothing, bedding and towels, which are usually washed by hand, without gloves, in cold water. Using protective equipment in the context of familial caregiving is sometimes seen as a sign of lacking compassion for the sick person.22 Gendered and generational divides within households can delay biomedical interventions. Younger relatives may advocate immediate hospital visits, while older relatives insist on ritual cleansing or other traditional measures first. Household dynamics related to caregiving and decision-making are also shaped by economic and personal factors that create diverse household practices beyond gender and age roles. Poverty and crowded living conditions make safe caregiving challenging.

Cross-border mobility

Transmission risks via informal routes: Informal footpaths through sugarcane fields in the Sio River region facilitate daily movements across the border. People using these routes avoid official health screenings.4 Families may relocate family members with suspected mpox across the border to avoid enforced isolation or registration. Leaving one’s immediate area may seem preferable to facing stigma at home. This practice undermines mpox contact tracing and may extend the outbreak to new areas.

Truck drivers as a high-risk mobile population: The first cases of mpox in Malaba involved a truck driver arriving from the DRC. Truck drivers often feel pressured to hide mild symptoms to avoid quarantine, fearing loss of income and lengthy border delays. This concealment risks further spread at truck stops, eateries and lodging facilities, where close contact (and sometimes sex work) is common.23

Additional cultural and social dynamics

School environments: Past experiences with chickenpox and scabies outbreaks indicate that infections can spread quickly in boarding school dormitories, particularly if an infection is concealed to avoid forced quarantine or negative publicity. Engaging school nurses and peer leaders is crucial: reinforcing ‘report without punishment’ protocols can mitigate spread. Teachers play an essential role in tackling stigma and playground rumours about the ‘monkey disease’. Some schools may establish an isolation room and many teachers coordinate with local health workers, alerting them to suspicious rashes and ensuring symptomatic children isolate early, reflecting the lessons learned from school closures experienced with COVID-19 and recent conjunctivitis cases.24 Schools with limited resources should adopt feasible measures such as regular checks and increased hygiene education, promoting a supportive environment for children and parents to report and manage symptoms without fear, and engaging community health workers and local leaders to assist with early detection and response efforts.

Market gossip and livelihood pressures: Markets function as social and information hubs. Many of the 23,000 people who cross the Busia-Malaba border daily are market traders passing between the urban centres in Busia-Busia. Traders (often women) rely on daily sales for income that is often part of a survival economy, for themselves and their dependents. As a result, traders may disguise minor mpox lesions rather than admit infection and risk the loss of income.

Clan-based enforcement: In certain Luhya and Samia communities, clan heads or local councils (LC1s) carry substantial authority. They can impose fines on families who hide contagious illnesses and may be an important point of contact in risk communication and community engagement.25

Data needed to strengthen the mpox response

There is a lack of systematic and up-to-date data on important aspects of mpox transmission and the response in the Busia-Malaba border region. Table 1 provides an overview of potential data points and methods that could be used to support the mpox response.

Table 1. Data and methods needed to support the mpox response in the Busia-Malaba border region

| Data point | Proposed method |

| Effectiveness of existing community health structures | Drawing on earlier community health system assessments, local enumerators can do quick ‘coverage audits’ and talk to community health workers to learn about the real obstacles community health workers face (e.g., lack of gloves, transport or local clan endorsement). |

| Behavioural economics of care | In prior responses to Ebola disease and cholera, small-scale ‘household budget diaries’ revealed how families chose cheaper herbal care when finances were tight. A similar approach could be applied during the mpox response: by briefly tracking how a few dozen families with suspected mpox allocate their limited resources, researchers could learn which interventions (e.g., emergency transport vouchers or partial treatment subsidies) could make early clinic visits more feasible. |

| Community perceptions of caregiving risks | More structured insights into how individual households assign caregiving duties are needed to pinpoint the real-time drivers of exposure and how families negotiate resource use (e.g., buying extra herbs versus paying clinic fees). Past local research on HIV care in polygamous relationships showed how quick community ‘care diaries’ or short interviews can provide insights into current household decision-making patterns and highlight realistic protective measures. |

| Evolving role of traditional healers | Drawing on methodology from earlier ‘traditional and biomedical integration’ initiatives, a rapid mapping of healer practices would clarify where to target further outreach and infection prevention training. |

| Mobility patterns of key groups | Past small-scale route mapping (e.g., how truckers and cross-border traders avoided official COVID-19 testing) could be replicated on a limited scale through informal interviews at known border crossings and stopping points. Similarly, short, trust-based conversations with sex worker peer educators can help track whether sex workers adopt new screening habits for clients or conceal illness. |

Source: Authors’ own.

References

- ICAP. (n.d.). A life saved, an outbreak prevented: How ICAP, CDC, and the Kenya Ministry of Health are preventing the spread of mpox. Retrieved 1 April 2025, from https://icap.columbia.edu/news-events/a-life-saved-an-outbreak-prevented-how-icap-cdc-and-the-kenya-ministry-of-health-are-preventing-the-spread-of-mpox/

- Vaccine doses allocated for 9 African countries hardest hit by mpox. (2024, November 6). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/vaccine-doses-allocated-9-african-countries-hardest-hit-by-mpox-2024-11-06/

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), & TA Networking Corp. (2022). Regional data collection survey and piloting of proposed activities aimed for the prevention of infectious disease at border posts (BPs) in the EAC: Final report. JICA. https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12369088.pdf

- King, P., Wanyana, M. W., Simbwa, B. N., Marrie, Z. G., Migisha, R., Kadobera, D., Kwesiga, B., Bulage, L., Gonahasa, D., Ahabwe, P. B., Mayinja, H., Owens, K. J., Itiakorit, H., Nchoko, S., Salat, E., Weithaka, F., Gunya, O., Odhiambo, F., Vicent, M., … Alex ArioKing. (2023). Cross border population movement patterns, Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda, November 2022. Uganda National Institute of Public Health (UNIPH) Quarterly Epidemiological Bulletin, 8(2), Article 3.

- Ssengooba, F., Tuhebwe, D., Ssendagire, S., Babirye, S., Akulume, M., Ssennyonjo, A., Rutaroh, A., Mutesa, L., & Nangami, M. (2021). Experiences of seeking healthcare across the border: Lessons to inform upstream policies and system developments on cross-border health in East Africa. BMJ Open, 11(12), e045575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045575

- Brown, H. (n.d.). Understanding the drivers of poor infection prevention control (IPC) practices in Kenyan health facilities: An interdisciplinary study. (In press). PLOS Global Public Health.

- Isaacs, S. N., & Mitjà, O. (2025). Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of mpox (formerly monkeypox). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-mpox-formerly-monkeypox

- Sikuku, L., Njoroge, B., Suba, V., Achieng, E., Mbogo, J., & Li, Y. (2023). Ethnobotany and quantitative analysis of medicinal plants used by the people of Malava sub-county, Western Kenya. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 26, 1–20.

- Logiel, A., Jørs, E., Akugizibwe, P., & Ahnfeldt-Mollerup, P. (2021). Prevalence and socio-economic factors affecting the use of traditional medicine among adults of Katikekile Subcounty, Moroto District, Uganda. African Health Sciences, 21(3), 1410–1417. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v21i3.52

- Ngere, S., Maixenchs, M., Khagayi, S., Otieno, P., Ochola, K., Akoth, K., Igunza, A., Ochieng, B., Onyango, D., Akelo, V., Blevins, J., & Barr, B. A. T. (2024). Health care-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses in western Kenya: Qualitative findings from the Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance (CHAMPS) Study (No. 8:31). Gates Open Research. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.14866.3

- Kukla, M., McKay, N., Rheingans, R., Harman, J., Schumacher, J., Kotloff, K. L., Levine, M. M., Breiman, R., Farag, T., Walker, D., Nasrin, D., Omore, R., O’Reilly, C., & Mintz, E. (2017). The effect of costs on Kenyan households’ demand for medical care: Why time and distance matter. Health Policy and Planning, 32(10), 1397–1406. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx120

- Isiko, A. P. (2018). Gender roles in traditional healing practices in Busoga [Doctoral thesis, University of Leiden] [Leiden University]. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/63215

- Paul, I. A. (2019). An expository study of witchcraft among the Basoga of Uganda. International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 6(12), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0612007

- Campbell, C., Skovdal, M., & Gibbs, A. (2011). Creating social spaces to tackle AIDS-related stigma: Reviewing the role of church groups in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 15(6), 1204–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9766-0

- Sitole, D. (2021, March 15). In Kenya, the pandemic has shown that church leaders are out of control. https://newhumanist.org.uk/5769/in-kenya-the-pandemic-has-shown-that-church-leaders-are-out-of-control

- Lee, Y. J., Coleman, M., Nakaziba, K. S., Terfloth, N., Coley, C., Epparla, A., Corbitt, N., Kazungu, R., Basiimwa, J., Lafferty, C., Cole, K., Agwang, G., Kathawala, E., Nkolo, T., Wogali, W., Richard, E. B., Rosenheck, R., & Tsai, A. C. (2025). Perspectives of traditional healers, faith healers, and biomedical providers about mental illness treatment: Qualitative study from rural Uganda. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 12, e29. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.18

- Manirabarusha, C. (2024, October 9). Stigma adds to Burundi’s challenges in mpox fight. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/stigma-adds-burundis-challenges-mpox-fight-2024-10-09/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, November 3). Let’s stop HIV together: HIV stigma. https://www.cdc.gov/stophivtogether/hiv-stigma/index.html

- White, L. (1990). The comforts of home: Prostitution in colonial Nairobi. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo3639384.html

- Booth, K. M. (Ed.). (2004). Local women, global science: Fighting AIDS in Kenya. Indiana University Press.

- Polygyny in Kenya by county. (2023). Kenya Data & Statistics. https://statskenya.co.ke/at-stats-kenya/about/polygyny-in-kenya-by-county/61/

- Brown, H. (2012). Hospital domestics: Care work in a Kenyan hospital. Space and Culture, 15(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331211426056

- Tom, P. A. (2025, January 24). Kenya’s truck drivers at the heart of the mpox outbreak. Health Business. https://healthbusiness.co.ke/8631/kenyas-truck-drivers-at-the-heart-of-the-mpox-outbreak/

- Mlamae, R. (2024, May 30). Red-eye disease forces Busia schools to dismiss students. Kwetu News. https://kwetucollections.co.ke/2024/05/30/red-eye-disease-forces-busia-schools-to-dismiss-students/

- Gumo, S. (2018). The traditional social, economic, and political organization of the Luhya of Busia District. Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 6(6), 1245–1257.

Authors: Hugh Lamarque (University of Edinburgh) and Hannah Brown (University of Durham).

Acknowledgements: We thank the following colleagues for their review of this brief: Oscar Gaunya (Kenya Ministry of Health, Disease Surveillance), Dr Matthew Muturi (Kenya Ministry of Health, Mpox Task Force), Dr Isaac Ngere (Medical Epidemiologist, Washington State University Center for Global Health, Nairobi, Kenya), Rosebel Ouda (independent researcher), Akiko Sakaedani Petrovic (UNICEF Kenya Country Office), Anastasiia Atif (UNICEF East and Southern Africa Regional Office), Douglas Lubowa Sebba and Tabley Bakyaita (UNICEF Uganda Country Office), Melissa Parker (LSHTM), Megan Schmidt-Sane (IDS) and Juliet Bedford (Anthrologica). Editorial support was provided by Harriet MacLehose. This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

Suggested citation: Lamarque, H. and Brown, H. (2025). Key considerations: Mpox in the Busia-Malaba border region linking Uganda and Kenya. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP). www.doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2025.022

Published by the Institute of Development Studies: May 2025.

Copyright: © Institute of Development Studies 2025. This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). Except where otherwise stated, this permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.

Contact: If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Juliet Bedford ([email protected]).

About SSHAP: The Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica , CRCF Senegal, Gulu University, Le Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, University of Ibadan, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

Keep in touch

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter