We could not be more excited to be involved in the launch of Social Science in Humanitarian Action: A Communication for Development Platform, a partnership between Institute of Development Studies and UNICEF, with support from Anthrologica. We hope it will pave the way for similar initiatives across the world.

We live in an age when, tragically, humanitarian emergencies are multiplying. Whether linked to health, disease and pandemics; to environmental disasters and climate change, or to conflict, political violence and refugee movements, the scale of human suffering is now greater than at any time since the Second World War. As the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul, May 23-24 2016 recognised, more than 130 million people around the world now need humanitarian assistance in order to survive. Effective humanitarian action is a global priority as never before.

The four “C’s”

Yet the humanitarian sector is also confronting major challenges. Some relate to resources and commitments from national governments and international agencies, which too often do not match up to the magnitude of the action required. Others relate to the effectiveness of that action. Does it properly fit national and local contexts, and conditions on the ground? Does it engage local communities, with sensitive, appropriate communication messages and messengers? Does it support continuity with ongoing development efforts and the work of national and local institutions, thus helping to build resilient systems that prepare for and mitigate future crises? Too often, and despite the best efforts of individuals, the answers to these questions are ‘no’. The structures of humanitarian action can easily encourage it to operate as a ‘bubble’, delivering one-off responses in standardised ways, divorced from complex on-the-ground- realities. These four ‘Cs’ – Context, Community engagement, Communication, and Continuity – often fail to get the attention they deserve, while the knowledge and information to act on them properly is lacking.

Our Platform responds to these challenges. It’s basic premise is simple: to bring social science knowledge in real-time into the heart of responses to humanitarian emergencies, thus enabling them to be more sensitive to conditions on the ground and to the perspectives of affected communities, and thus more effective overall. Through accessible helpdesk responses, briefings and syntheses, it aims to provide the information humanitarian actors and agencies need when, how and in forms that suit them.

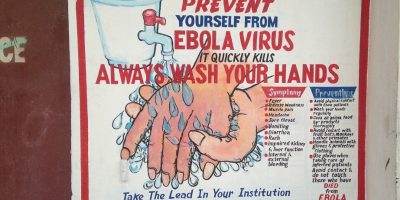

‘Proof of concept’ for this approach – and for the value of social science in delivering on the four Cs – was provided during the Ebola crisis in West Africa during 2013 – 15, when IDS and partners (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the universities of Sussex, Exeter and Njala, Sierra Leone) set up and ran the Ebola Response Anthropology Platform (ERAP). As the devastating Ebola epidemic unfolded, the initial public health and humanitarian response faltered – not least for social and cultural reasons. Actions by external teams to halt transmission – such as confining the ill in Ebola Treatment Units, imposing quarantines and restricting funerals – failed to gain community support and were often resisted. ERAP mobilised long-term social science research on the region’s community structures and institutions, health and social change, and embedded social, economic and political histories and contexts to inform the response. The Platform was able to deliver real-time, social evidence-based advice to policy and practice where rapid support was needed and solicited, whether in identifying and diagnosing cases; managing death and funerals; caring for the sick; improving communications and community engagement, and addressing social resistance and violence against health workers. Many humanitarian agencies acknowledged the value of ERAP in rendering their work more sensitive and thus effective, especially in informing approaches to communications and dialogue that supported communities’ own learning and behaviour change – now acknowledged as key to turning the epidemic around.

Social and Emotional Intelligence

Post-Ebola, influential actors have argued to extend this kind of approach. The UK Government Chief Scientist, for instance, cited ERAP when calling for mechanisms to integrate social science evidence in addressing all global challenges. The UN Special Envoy on Ebola, David Nabarro, stated in an open letter that ‘this approach was appreciated by Governments, the UN system, civil society and donors. It contributed to the social and emotional intelligence of the response, helping with the establishment of interventions perceived, by people at risk, as both rational and acceptable; and perceived by the responders as meaningful and achievable. The approach has helped the identification of priorities for the building of more resilient health systems, governance and society. It is inevitable that applied and adapted anthropological capabilities will be in greater demand in infectious disease outbreaks and many other situations to come.’

The Platform responds directly to this wider call to integrate anthropological and other social science capabilities into humanitarian action. With its initial focus on health-related emergencies in East and Southern Africa, I’m greatly looking forward to shaping and developing it in interaction with the work of UNICEF and its partners there, helping to inform and attune their work in these settings. More broadly, I’m hopeful that this can be a step towards building a future in which social science helps to bring context, community engagement, communication, and continuity to the heart of all kinds of humanitarian action, everywhere.