The experiences of those fleeing from Sudan to South Sudan due to the current conflict are shaped by the complex socio-political dynamics within and between the two countries.

This briefing (published 28 July 2023) focuses on the historical and socio-political dynamics that need to be taken into consideration by humanitarian agencies when they are providing assistance and protection to South Sudanese fleeing from Khartoum and other parts of Sudan to South Sudan, and to Sudanese fleeing Sudan to seek refuge in South Sudan.

This briefing note was prepared by Naomi Pendle, Jennifer Palmer, Melissa Parker, Nelly Caesar Arkangelo, Machar Diu Gatket and Leben Moro. It draws on recent personal experiences, established research connections and emerging information about the evolving situation in both countries.

Key considerations

- Before 2011, Sudan and South Sudan were one country. Secession politics is shaping how people in South Sudan receive those moving across the new international border between the two countries.

- Although divisions have been created by a long history of socio-economic inequalities, there is also a long history of close relationships, movement and blurred lines between what are now Sudan and South Sudan.

- It cannot be assumed that the external categories ‘refugee’ and ‘returnee’ well represent how Sudanese and South Sudanese think about their status after arriving in South Sudan.

- Sudanese fleeing to South Sudan to stay with family or friends may not seek assistance or be aware of information available to refugees, and they may be easily overlooked by humanitarian agencies.

- South Sudanese fleeing to South Sudan may not feel they are returning ‘home’ or to safety.

- The use of refugee and returnee labels can have negative social and political connotations. Refugees may be directed to settle in camps while returnees may be told to go to ‘home’ areas; both options potentially limit freedom of movement and carry protection risks.

- Government and humanitarian agencies should support people to reach the destinations of their choice as much as possible. They should also recognise that many South Sudanese coming from Khartoum may not have access to land or the livelihood skills needed to transition easily to subsistence farming and other common livelihoods in South Sudan.

- In South Sudan, some people assume that the South Sudanese who chose to live in Khartoum were those more likely to be politically aligned to opposition groups in South Sudan. This assumption may produce anxiety around those returning from Khartoum, especially as elections are currently scheduled to take place in South Sudan in 2024.

- People who were living in Khartoum because of alienation and neglect by their ‘home’ communities in the South are particularly vulnerable to abuse and may face extreme poverty. This includes war widows and their children.

- Humanitarian agencies should be alert to the complex socio-political and economic dynamics between returning South Sudanese and those who are already living in South Sudan.

- Distributions of aid occur in a context of protracted food insecurity in South Sudan. Assistance should also be provided to those in South Sudan who are hosting people who have fled Sudan.

- Providers of emergency health services at reception points and in transit camps should expect that these services will also be needed and requested by surrounding host communities.

- People entering South Sudan report feeling particularly anxious about their vulnerability to infectious disease outbreaks in crowded camps. They will require information about the ongoing outbreaks of cholera, hepatitis E and measles in camps and other areas.

- South Sudanese who have been living in Sudan since before South Sudan seceded, and their children, may not have ever procured South Sudanese identity cards while others may have lost them during flight. Some people have reported difficulties crossing the border and at checkpoints in both countries. South Sudanese without identity cards require information on their citizenship rights and support to procure the needed documentation at border crossings.

- Humanitarian agencies should not apply ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions to those fleeing to South Sudan. Needs assessments should be sensitive to people’s socio-political situations and how they may affect the security and reintegration challenges of displacement. Communication channels should be established with different population groups.

- Local communities in both countries, and across national identities, have been supporting people on the move and recent arrivals in small but meaningful ways.

- Churches have provided crucial support to South Sudanese in Khartoum, and they have the potential to play a continued supportive role. They should be included in humanitarian communication and coordination strategies.

Background context

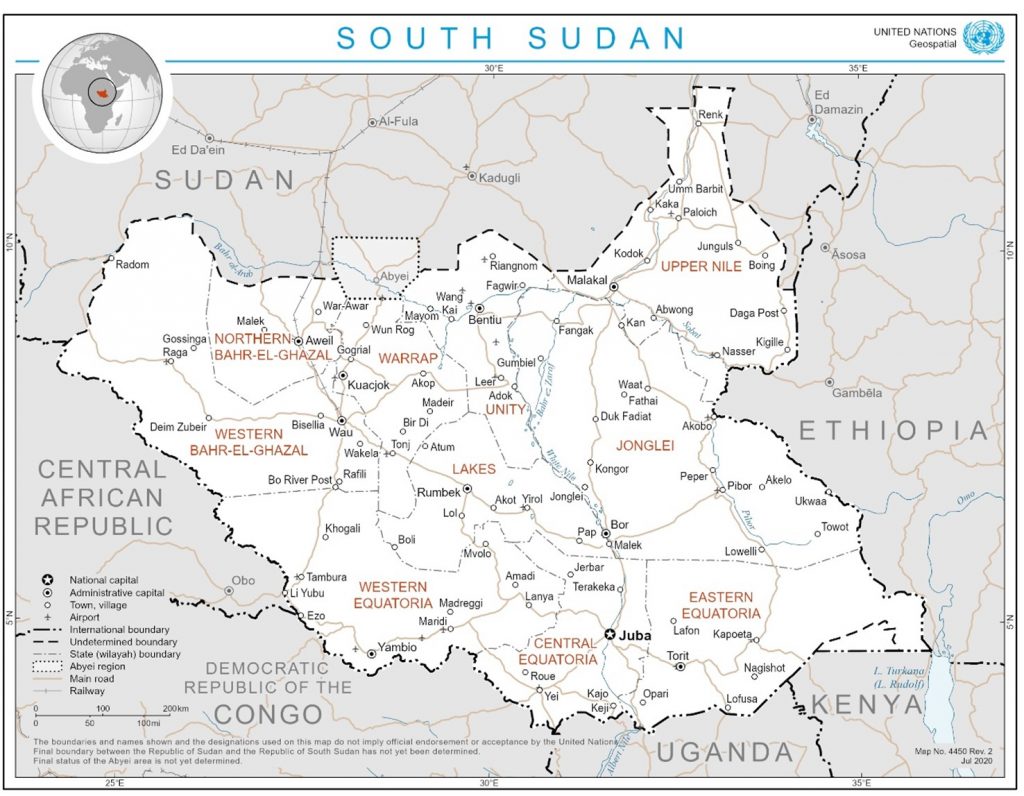

Figure 1. Map of South Sudan

Source: © United Nations, Map No. 4450 Rev. 2, 2020. Reproduced with permission.

Sudan-South Sudan relations

The legacies of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium rule (1899-1955) have shaped the political and economic trajectories of Sudan and South Sudan (formerly known as Southern Sudan). Before and after independence of Sudan, in 1956, Southern Sudanese people were largely isolated from large-scale development initiatives and opportunities for political leadership, which were concentrated in the north.

While many Southern Sudanese groups, including the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), fought against successive Khartoum-based governments in the first (1955-1972) and second (1983-2005) civil wars, other groups felt alienated or persecuted by these rebels. Some of the groups and leaders who felt alienated by the rebels and who opposed SPLA brokered deals with the Sudanese government. Many of these groups found safety and a base in Khartoum.

Hundreds of thousands of Southern Sudanese fled to Khartoum for safety during the civil wars. For many who fled, the choice of Khartoum was based on safety, physical proximity to areas in Southern Sudan where they were already living, or educational and employment opportunities; their choice was not based on political alliances. However, some people in Southern (now South) Sudan came to assume that residency in Khartoum equated to not supporting the SPLA.

A peace agreement in 2005 created a new Government of Southern Sudan and promised independence in 2011. This peace agreement also made SPLA the dominant party in the new government. In 2006, the new Southern Sudanese president, Salva Kiir, brokered the Juba Declaration with southern anti-SPLA groups who had been funded by the Sudan government. These groups often had close relations and/or residency in Khartoum.

When those who had fled Southern Sudan during the second civil war returned to South Sudan post-independence, they had diverse experiences of homecoming and reintegration. These experiences were often influenced by their choice of country of refuge and how it was perceived by others. People’s wartime experiences, alliances and contributions were often (inaccurately) judged based on where they had fled. Those who joined or supported SPLA were more likely to seek refuge in East Africa. Those who fled to East Africa adopted different languages (particularly English) and cultural norms from those who went to northern Sudan (where people continued to use Arabic to communicate outside their ethnic group).

Post-independence, tensions among communities and in families in South Sudan are often expressed through disagreements about daily routines, but these disagreements are stand-ins for deeper tensions about differing wartime contributions and the current balance of political power in the country.1 The SPLA has controlled the South Sudan government post-independence.

Despite the divisions between some South Sudanese and Sudanese people – created by successive governments and a long history of socio-economic hierarchies and inequalities – there is a long history of close relationships and blurred lines between these nationalities. South Sudanese were Sudanese until southern independence in 2011, and many South Sudanese living in Khartoum still identify as being Sudanese.

After conflict erupted between the South Sudanese government and armed opposition groups in 2013, the Sudanese government spoke of the quasi-citizenship of South Sudanese in Sudan and initially maintained an open-door policy for South Sudanese. However, in 2016, a memorandum of understanding between the Sudanese government and UNHCR stated that South Sudanese in Sudan were ‘refugees’ (and not quasi-citizens) and, therefore, should be in refugee camps. From this point, UNHCR focused its support on refugee camps. However, the majority of South Sudanese opted to continue living in Khartoum and in other cities, often as they did not want the perceived indignity of being treated as refugees.2

In the last decade, instability and war have shaped daily life in many parts of South Sudan. A total of 2.2 million people are internally displaced within the country3 and 2.1 million refugees have been displaced from the country, including to Sudan. At the same time, as of March 2023 (before the current outbreak of violence in April 2023), South Sudan hosted 280,000 refugees from Sudan because of conflict.4

Intersecting crises in South Sudan

South Sudan is currently facing multiple, intersecting crises. They strain basic services for people living in South Sudan and new arrivals, and they also complicate the provision of humanitarian relief.

Ongoing conflicts: South Sudan’s main warring parties signed a revitalised peace agreement in 2018. However, delays in its implementation and a fragmented security landscape mean that South Sudan continues to experience high levels of armed conflict. Since November 2022, major and protracted violent incidents occurred in Upper Nile, Jonglei, Central Equatoria and Western Equatoria states.5,6 Humanitarian workers and food convoys also continue to be targeted.5

Economic crises: South Sudan’s main export is oil. South Sudanese leaders worry that continued fighting in Sudan could negatively affect oil production, as the pipelines to the export terminals on the Red Sea pass through Sudan. The country’s oil revenues increased in 2022, due to increases in the global price of oil, but were spent mainly on prominent political and security institutions, leaving health, education and other basic services to be largely funded through foreign aid.5 The cost of living has increased, with the South Sudanese pound losing nearly 60% of its value between July 2021 and September 2022. The country has also experienced large cuts in foreign aid as a consequence of the global recession.

Flooding: In recent years, extreme seasonal flooding has disrupted access to land and food. By 2022, all the 10 states and three administrative areas in the country had been affected by floods and over a million people had been displaced,7 compounding other humanitarian challenges. Flood waters continue to block humanitarian access in some parts of Unity and Jonglei states. The water, sanitation and hygiene situation in camps for internally displaced people (IDP) in these states has become worse since May 2023.8

Food insecurity: In 2023, 54% of South Sudanese were reported to be experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity, with an estimated 2.2 million people being on the edge of famine and experiencing emergency levels of food insecurity.9 Maintaining access to markets has been a key way for people in South Sudan to survive conflict- and climate-induced food insecurity. However, this access is becoming increasingly restricted because of high inflation rates. The current crisis in Sudan is compounding the problem by decreasing access to Sudanese markets; this is most notably an issue in Warrap, Unity, Northern and Western Bahr el Ghazal, and Upper Nile states. These states border Sudan and only have access to East African markets via broken and sometimes dangerous roads.

As a result of these intersecting crises, displacement is now at its highest level since the peace agreement was signed in 2018,10 and food insecurity is at its highest level since independence in 2011.6

Humanitarian considerations in a context of circular return

The current conflict in Sudan is displacing Sudanese and South Sudanese people who were living in Sudan to South Sudan. South Sudanese people, in particular, now face the prospect of circular return, which occurs when refugees and displaced populations repeatedly move or rotate, often over decades, between an origin and a destination location.11 For some South Sudanese, returning to South Sudan is not seen as returning ‘home’.

For many reasons, the movement of South Sudanese and Sudanese to South Sudan has led to a blurring of the lines between the categories of ‘refugee’ and ‘returnee’. While use of refugee and returnee terminology can be helpful for administrative purposes to formalise and enhance support, the application of these labels can also have negative social and political connotations, which are discussed in the sections below.

Some refugees and returnees are being directed to settle in camps while other returnees are being told to go to ‘home’ areas. Both destinations potentially limit freedom of movement and livelihood opportunities and affect health, protection and wellbeing. Government and humanitarian agencies should assist people coming from Sudan to reach destinations of their choice and support these transitions as best as they can.

South Sudanese in Sudan

- Many South Sudanese have lived in Sudan for decades and South Sudanese children born there may never have visited South Sudan.

- Recent research showed that a large number of South Sudanese in Khartoum regarded themselves as ‘locals’, particularly those who were born in or had lived in the northern part of Sudan before separation in 2011.2

- The socio-economic conditions of South Sudanese living in Khartoum vary significantly.

- Sudan’s wars have taken place mainly in the peripheries of the country and, until recently, Khartoum was viewed as a place of safety. Khartoum has been a particularly important and attractive place for South Sudanese – many moved there to access higher education and health services.

- The last century of Sudanese politics marginalised the areas of Sudan far from Khartoum, including Darfur and what is now South Sudan. This history of marginalisation has encouraged discrimination against many South Sudanese in Khartoum. However, a person’s wealth, cultural and social behaviour, language and religion may reduce their day-to-day experience of discrimination. During research with South Sudanese in Khartoum in 2022, it was observed that even those who faced discrimination still retained strong bonds with Khartoum and had more links with Sudanese people than with South Sudanese.2

South Sudanese returnees

Flight

- Before the outbreak of violence in April 2023, there were 800,000 South Sudanese registered as refugees in Sudan, with many others not being registered this way with government or humanitarian agencies. As of June 2023, 149,000 South Sudanese had been displaced within Sudan, mainly from Khartoum southwards to White Nile state. This state was already hosting 110,000 South Sudanese in refugee camps.12

- South Sudanese living in informal settlements and poorer neighbourhoods in Khartoum reported feeling very vulnerable to violence as their shelters offered little protection when conflict erupted.13

- The high level of poverty of some South Sudanese in Sudan has reduced their ability to flee. Fundraising and information-sharing by South Sudanese civil society groups and Sudanese neighbourhood resistance committees have played an important role in helping South Sudanese people board buses to leave the city.13

- Going through White Nile state is a popular route for people making the long and difficult journey to South Sudan via Renk in Upper Nile state. As of 20 June 2023, 117,000 South Sudanese classified as ‘refugee returnees’ had entered South Sudan from Sudan.14

- Many South Sudanese are still making their way to South Sudan as the situation in Sudan, and Khartoum in particular, continues to deteriorate.

Reception and transit

- South Sudanese who have been living in Sudan since before South Sudan seceded in 2011, and their children, may not have identity cards to prove their citizenship rights in South Sudan, either because they never procured them when the countries separated or because they lost them, potentially during flight. Some have reported experiencing difficulties crossing the border and at checkpoints throughout insecure areas in both countries.15 Understanding returning people’s legal status in South Sudan was a key information need identified in recent surveys of people crossing the border. People on the move require information on their rights and support to procure documentation at border crossing points.

- It has been reported that when reaching Upper Nile state, some South Sudanese managed to board free flights to Juba. Local authorities have since stopped free flights and indicated that, in future, flights will only be to return people to their ‘home’ areas. Many who can afford it try to purchase tickets on cargo planes flying from Paloich to Juba.

- Airports near the border and sites in Renk, Roriak and Malakal that have been repurposed as transit or reception centres, such as a university campus and an old military barracks, have been overwhelmed. The need for water, sanitation, food and shelter in these locations has outpaced the capabilities of the responding organisations.16–18

- South Sudan is also being used by some people fleeing Sudan to cross into other countries, such as Uganda and Kenya. Those using this route include South Sudanese who fled South Sudan between 2013 and 2016 because of persistent insecurity and who do not feel safe returning, and those for whom life in Juba is prohibitively expensive.

Settlement considerations

- South Sudanese people who live in South Sudan have varied perceptions of people who fled to Sudan or stayed after independence in 2011. There is a part of the public who are unhappy with those in Sudan, who, they believe, did not commit to or want independence. There are also those who are sympathetic to the people who stayed in Sudan but who are not comfortable expressing this opinion for fear of angering powerful individuals or institutions.

- Some South Sudanese in Juba have been using discriminatory language against those coming from Sudan. Media have reported that some people think that a long-term camp for returnees should be created and called ‘Malesh Salva Kiir’ (‘Sorry [South Sudanese President] Salva Kiir’). This name is suggested because when South Sudanese returned to Sudan after the outbreak of fighting in South Sudan in 2013, the migration was interpreted as an apology to the then Sudanese president, Bashir, for voting for independence.

- Returning South Sudanese are likely to be much more reliant on support from civil society, social networks and humanitarian programmes than on support from the South Sudanese government, which is already constrained by limited systems and resources.

- During other large-scale returns to South Sudan (and previously southern Sudan), such as after the 2005 peace agreement, and during more recent attempts to close UN Protection of Civilian (PoC) sites and IDP camps, some politicians in South Sudan called for people to go to their ‘home villages’. ‘Home villages’ was used to refer to the traditional homelands of the different ethnic groups in the country. This strategy of calling for people to go to their home villages serves a variety of political purposes, including demonstrating peace, as the movement to home villages suggests people believe it is safe to travel and that the people in power are enforcing peace agreements, even when security may actually be elusive. Other purposes of the strategy are to consolidate power through larger ethnic and geographic constituencies and to reduce the risk of land conflicts, especially in Juba.

- Among the many criticisms of the ‘home villages’ strategy is that it undermines freedom of movement, which has implications for livelihoods and wellbeing. Sending people to their ‘home villages’ has been discussed as a solution to the ‘problem’ of receiving current returnees.

- Rather than enforcing a return to a ‘home village’ or settlement in a camp designated for returnees, government and humanitarian agencies should support people to reach destinations of their choice as much as possible.

- People’s decisions to leave Sudan were made quickly, with little chance to gather information to plan their move or reintegration into South Sudanese society.

- Many returnees do not have a home or social network to return to. They may also not have the livelihood skills used by most South Sudanese to survive, such as those for subsistence farming. As many returnees have no access to land, social connections or a way to generate income for essentials in their ‘home village’, some fear that they will fail to establish a life and livelihood for themselves.

- For example, women widowed in the war in the 1990s were sometimes alienated by their husband’s family as, with large numbers of war dead and conflict-induced crisis levels of food insecurity, the family could not afford to support them. Many widows opted to sever ties with their husband’s family and go to Khartoum to work. There may be nothing waiting for them if they return to South Sudan.

- Some returnees may not be familiar with the fragile security situation in South Sudan, having spent most of their adult lives in Sudan. Humanitarian agencies should consider these returnees’ information needs when supporting people to make travel and initial settlement decisions.

- Returning to South Sudan does not necessarily mean returning to safety.19 Despite the 2018 peace agreement, armed conflict continues, albeit often between different groups. UN peacekeeper protection has declined in PoC sites, forcing some South Sudanese to hide their ethnic identities to stay safe.20 For example, many South Sudanese from the Nuer ethnic group (many members of which fought against the South Sudanese government in the conflict that started in 2013) cover their facial markings (called gaar) and avoid engaging in land and property disputes connected to the 2013 violence, even though resolving these disputes may enable them to leave PoC sites.

- Many South Sudanese fleeing from Khartoum have friends and relatives in the former PoC sites in Juba and Bentiu and the current PoC site in Malakal. These sites are likely destinations for some South Sudanese coming from Khartoum. It is unclear how the arrival of returnees will impact safety and the local political dynamics of the sites.

Sudanese refugees

- A large number of Sudanese have fled Khartoum by road, going to Egypt, Ethiopia or other areas in Sudan, such as Wad Medani, Kassala, Al-Ghadarif and Port Sudan. As of 20 June 2023, 6,500 Sudanese, along with 3,000 asylum seekers from other countries, had entered South Sudan to escape the conflict.14

- The relatively small number of Sudanese from Khartoum seeking refuge in South Sudan reflects the fact that the majority of Sudanese have very few ties to South Sudan. Moreover, the country is perceived as having a very different way of life to Sudan and as being insecure.

- Sudanese who live closer to the border with South Sudan might find it easier to cross to South Sudan than to travel elsewhere, but at the time of writing, there is not known to be significant displacement by Sudanese to South Sudan from bordering states.

- Sudanese who have fled to South Sudan are likely to be those with existing familial ties there through birth or marriage and those with long-standing economic connections (such as through family working as traders). They may not self-identify as refugees, and they may not seek assistance or be aware of information available to refugees and may be easily overlooked by humanitarian agencies.

- Pastoralists in both countries have a long history of crossing into lands on either side of the border and broker seasonal agreements with traditional and political authorities for permission and safe passage. In Northern Bahr el Ghazal, there are Rezigat cattle keepers from Sudan who would normally be expected to return to Sudan in July, but have requested to spend the year in South Sudan to avoid the conflict in Sudan. Government and United Nations bodies are open to this, and recognise the need for peace-sensitive strategies to accommodate pastoralists to minimise the risk of conflict with other people growing crops. The Rezigat, like most seasonal migrants, do not identify with the term ‘refugee’.

Response in South Sudan

- Humanitarian agencies must be careful to not apply ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions to those fleeing to South Sudan from Sudan. Needs assessments undertaken by humanitarian agencies should be sensitive to socio-political dynamics and how they may affect the security and reintegration challenges of displacement. Communication channels should recognise these dynamics and be established with different population groups.

- Local communities have been supporting people on the move and recent arrivals from Sudan in small but meaningful ways. Churches have provided crucial support to South Sudanese in Khartoum, and they have the potential to play a continued supportive role. They should be included in humanitarian communication and coordination strategies.

- In all programme planning, humanitarian agencies should be aware of the potential impacts of the forced displacement from Sudan on the existing population living in South Sudan. Basic services and infrastructure in the country are already chronically stressed because of intersecting emergencies.

Protection

- Many of those crossing Sudan’s borders arrive in a vulnerable condition – they have often been separated from family members and are in need of humanitarian assistance in often remote and underserved areas.

- There have been reports of people fleeing the conflict being stopped and abused by armed forces in Sudan. Many women, girls and unaccompanied children on the move to South Sudan are at risk of trafficking as they lack the financial means to pay for safe transport, heightening the risk of gender-based violence.

- South Sudanese opted to live in Khartoum for various reasons. However, in South Sudan, some people assume that the South Sudanese in Khartoum were aligned to armed groups opposing SPLA. This assumption prompts some in the South Sudanese security forces to believe that people of certain ethnicities who were living in Khartoum are unlikely to be loyal to the government. This security force anxiety may produce violence against civilians.

- Elections may occur in 2024 in South Sudan, and the security forces could have concerns that the ongoing large-scale movement of people could cause complications in the election process and change alliances in certain areas. These concerns could increase security force anxiety about and violence against certain ethnic groups coming from Sudan.

- People who were living in Khartoum because of alienation and neglect by their ‘home’ communities in the South are particularly vulnerable. This includes war widows and their children. If they are unable to find safe family networks in rural areas, they are likely to remain in urban centres. The socio-economic conditions in South Sudanese towns are different from those in Khartoum, and these women and children may be particularly open to abuse as they navigate the new dynamics.

Food insecurity

- In South Sudan, there is a long history of United Nations agencies providing food assistance to ‘host’ communities as well as displaced populations. However, in 2023, for the first time in 30 years, some areas of northern South Sudan did not receive food assistance, due to cuts in foreign aid budgets.

- Food insecurity is most acute for resident South Sudanese populations in Jonglei, Upper Nile, Unity, and Warrap states.21 April to July are the ‘hungriest’ months in South Sudan as crops are not produced until August or September, after the rainy season. The reduction in food assistance will have the greatest impact in these hungriest months.

- Food is the most important need indicated in the needs assessments of people crossing the Sudan–South Sudan border.22

- Children arriving in Juba, with and without family, are reported to be facing days with almost no food unless their parents have friends or relations for them to call on.

- Many areas considered to be people’s ‘home villages’ (see above) have not recovered from the flooding in 2022 that caused widespread destruction of crops, livestock, and water and sanitation infrastructure. These areas remain flood-prone and with heightened food insecurity.

- Any food assistance offered to and accepted by people moving to South Sudan from Sudan will be against a backdrop of food insecurity and other protracted humanitarian crises.

Health care

- Most people arriving at border points are physically and psychologically exhausted, and some also have severe injuries from the conflict or their flight.

- With 61% of hospitals in Khartoum closed following attacks and looting,15 many people who have fled have been without access to emergency health care and services for sexual and reproductive health and communicable and non-communicable diseases for more than two months.

- People coming from Khartoum may be accustomed to much better access to health care than that available in the northern states of South Sudan where they are entering the country. How to access medical care is among the top three information needs reported by households crossing into South Sudan.22

- At screening and transit points, the number of cases of malnutrition identified in under-fives has been increasing. Malnutrition increases vulnerabilities to common infections and makes other health conditions more difficult to manage.16

- The global economic crisis led to dramatic cuts in international donor funding to the health care sector in 2022. The Health Pooled Fund, which is responsible for health-care provision in eight of the 10 states in South Sudan, cut funding to over a quarter of the facilities it supports, impacting nutrition services and supplies of essential drugs.21

- South Sudanese people often experience dramatic changes in their access to health care because of changes in the funding landscape. Many communities have developed strategies to share detailed information about how to access and take advantage of services when they become available 23,24 and to lobby humanitarian agencies and parliamentarians when services are not available.25 As a result, when emergency health-care services are provided in response to large influxes of people, health-care access tends to improve for everyone.

- Emergency health services and mobile clinics are being set up to serve reception points and transit camps. Providers should expect that these services will also be needed and requested by surrounding host communities.

- The psychosocial and mental health impacts of circular return are poorly documented, but there is no doubt that they are amplified by the day-to-day challenges of accessing water, food, shelter, and health care.26 People’s decisions to leave Sudan were often made very quickly, with little chance to withdraw money from banks, sell assets, or gather information to plan their move, survival, and reintegration into South Sudanese society. Transitions such as this, which involve mobilising resources and adjusting to new moral and social realities, are complex and difficult, especially when people have not had the chance to plan their ‘homecoming’ over a long period.27

- Transit camps can offer new arrivals a vital opportunity to rest and access health-care services. However, entering and living in a transit or IDP camp can cause anxiety and distress for diverse reasons, including the restrictions on movement and livelihoods and the highlighting of a migration status that has political connotations and carries protection risks. Additionally, the close quarters of a camp setting can be particularly distressing for women, who may fear enhanced social surveillance of their sexual and reproductive behaviours.28

- People entering South Sudan also report feeling particularly anxious about their vulnerability to infectious disease outbreaks in crowded camps17 but may not be aware of the specific risks from the ongoing outbreaks of cholera in Malakal town and IDP camp, hepatitis E in Bentiu IDP camp, and measles in multiple locations across the country.8 Given that all these outbreaks are controlled by vaccines, new arrivals unfamiliar with health care in South Sudan may require additional information and reassurance about vaccine safety as well as about the organisations providing the vaccines.24

- The crisis in Sudan has interrupted access to health care for people in South Sudan. Many South Sudanese used to travel to Khartoum and Omdurman to receive specialist health care. Recent research highlighted how families that could afford it would invest significant resources in sending senior family members to Khartoum for health care as a sign of respect and doing all that is possible to care for people before death.29 South Sudanese also seek health care in Uganda, Kenya, UAE, India, Egypt, South Africa and Jordan, and these destinations are now more likely to be used over Sudan.

References

- Akoi, A. D., & Pendle, N. R. (2020). ‘I Kept My Gun’: Displacement’s Impact on Reshaping Social Distinction During Return. Journal of Refugee Studies, 33(4), 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa087

- Caesar Arkangelo, N. (n.d.). Ongoing research.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). (n.d.). IOM displacement tracking matrix South Sudan—Event tracking: Displacement and return. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNjc1YTBhMmUtMDg3OC00NTY1LThhYWMtODRmMjY3ODZiNTQ 0IiwidCI6IjE1ODgyNjJkLTIzZmItNDNiNC1iZDZlLWJjZTQ5YzhlNjE4NiIsImMiOjh9

- (n.d.). Operational data portal—Refugee situations—South Sudan. https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/ssd

- UN Panel of Experts on South Sudan Established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2206 (2015). (2023). Letter dated 26 April 2023 from the Panel of Experts on South Sudan addressed to the President of the Security Council. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4010177

- Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2023). South Sudan: Humanitarian Snapshot (April 2023) – South Sudan. https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-humanitarian-snapshot-april-2023

- Moro, L. N. (n.d.). Flood Assessment in South Sudan November 2022. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform. https://www.socialscienceinaction.org/resources/flood-assessment-in-south-sudan-november-2022/

- (2023, June 2). Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and other Emergencies: Week 22: 22-28 May 2023 (Data as reported by: 17:00; 28 May 2023) – Democratic Republic of the Congo. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/weekly-bulletin-outbreaks-and-other-emergencies-week-22-22-28-may-2023-data-reported-1700-28-may-2023

- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification. (2022, November 3). South Sudan: Acute Food Insecurity Situation October—November 2022 and Projections for December 2022—March 2023 and April—July 2023. https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1155997/?iso3=SSD

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). (n.d.). Country profile—South Sudan. IDMC. https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/south-sudan

- Tegenbos, J., & Vlassenroot, K. (2018, May). Going home? A systematic review of the literature on displacement, return and cycles of violence (Monograph No. 1). Conflict Research Programme, London School of Economics and Political Science. http://lse.ac.uk/Africa/research/politics-of-return

- UNHCR Sudan. (n.d.). Overview of refugees and asylum seekers distribution and movement in Sudan Dashboard as of 18 June 2023. UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/101363

- Gatket, M. D. (n.d.). Leaving Sudan: A cyclical journey to safety. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform. https://www.socialscienceinaction.org/blogs-and-news/leaving-sudan-a-cyclical-journey-to-safety/

- (n.d.). Operational data portal—Refugee situations—Sudan. https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/sudansituation

- (2023, June 4). Sudan Country Refugee Response Plan Addendum, January – December 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/sudan-country-refugee-response-plan-addendum-january-december-2023

- (2023, June 1). UNICEF South Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report and Fact Sheet (Response to the Sudan Crisis): 19 May 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/unicef-south-sudan-humanitarian-situation-report-and-fact-sheet-response-sudan-crisis-19-may-2023

- (2023, May 16). Humanitarian disaster looming ahead of rainy season in Renk in South Sudan. https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/humanitarian-disaster-looming-ahead-rainy-season-renk-south-sudan

- Save the Children. (2023, May 11). Children fleeing Sudan arriving at borders withdrawn, anxious and scared, says Save the Children. https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/children-fleeing-sudan-arriving-borders-withdrawn-anxious-and-scared-says-save-children

- Research and Evidence Facility & Samuel Hall. (2023). South Sudan’s decades of displacement: Understanding return and questioning reintegration. EU Trust Fund for Africa (Horn of Africa Window) Research and Evidence Facility. https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudans-decades-displacement-understanding-return-and-questioning-reintegration

- Janguan, T., & Kirk, T. (2023). Hiding in plain sight: IDP’s protection strategies after closing Juba’s protection of civilian sites. Global Policy. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13206

- Nutrition Cluster & UNICEF. (2023, May 22). South Sudan Nutrition Cluster Bulletin Issue 1 (May 2023). https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-nutrition-cluster-bulletin-issue-1-may-2023

- (2023, May 30). Sudan Crisis: Cross-Border Assessment – Returnee / Refugee Household Survey (May 2023) – South Sudan. https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/sudan-crisis-cross-border-assessment-returnee-refugee-household-survey-may-2023-south-sudan

- Palmer, J. J., Kelly, A. H., Surur, E. I., Checchi, F., & Jones, C. (2014). Changing landscapes, changing practice: Negotiating access to sleeping sickness services in a post-conflict society. Social Science & Medicine, 120, 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.012

- Peprah, D., Palmer, J. J., Rubin, G. J., Abubakar, A., Costa, A., Martin, S., Perea, W., & Larson, H. J. (2016). Perceptions of oral cholera vaccine and reasons for full, partial and non-acceptance during a humanitarian crisis in South Sudan. Vaccine, 34(33), 3823–3827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.038

- Duclos, D., & Palmer, J. (2020). Background Paper: COVID-19 in the Context of Forced Displacement: Perspectives from the Middle East and East Africa.

- Roberts, B., Damundu, E. Y., Lomoro, O., & Sondorp, E. (2009). Post-conflict mental health needs: A cross-sectional survey of trauma, depression and associated factors in Juba, Southern Sudan. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-7

- Mergelsberg, B. (2010). Between two worlds: Former LRA soldiers in northern Uganda. In T. Allen & K. Vlassenroot (Eds.), The Lord’s Resistance Army: Myth and reality (pp. 156–176). Zed Books.

- Palmer, J. J., & Storeng, K. T. (2016). Building the nation’s body: The contested role of abortion and family planning in post-war South Sudan. Social Science & Medicine, 168, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.011

- Pendle, N. R. (n.d.). Ongoing research.

Acknowledgements

This brief has been written by Naomi Pendle (University of Bath), Jennifer Palmer (LSHTM), Melissa Parker (LSHTM), Nelly Caesar Arkangelo, Machar Diu Gatket, and Leben Moro (University of Juba) with support from Diane Duclos (LSHTM) and Juliet Bedford (Anthrologica). An earlier version of this brief was discussed at a roundtable facilitated by SSHAP in June 2023 with an expert advisory group on the Sudan crises, including Jok Madut Jok, Nada Mustafa, Rahsa Ahmed, Abraham Ding, Mohamad Bakhit, Wol Athuai, Monzoul Assal, Tom Kirk, Hayley MacGregor, Eva Niederberger, Megan Schmidt-Sane, and Grace Akello. The brief was edited by Nicola Ball (SSHAP editorial team). The brief is the responsibility of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP).

Contact

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Juliet Bedford ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica, CRCF Senegal, Gulu University, Le Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, University of Ibadan, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

Keep in touch

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Pendle, N.; Palmer, J.; Parker, M.; Caesar Arkangelo, N.; Diu Gatket, M. and Moro, L. (2023) Crisis in Sudan: Briefing Note on Displacement from Sudan to South Sudan, Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP), DOI: 10.19088/SSHAP.2023.017

Published July 2023

© Institute of Development Studies 2023

This is an Open Access brief distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.