Introduction

This brief illustrates how COVID-19 vaccine (in)equity has played out on the ground and offers key considerations for how it can be improved in the North West London (NWL) borough of Ealing. We conducted a review of literature and several informal consultations with local actors involved in COVID-19 vaccination efforts in statutory bodies (local authorities and the NHS) and the community in order to build a picture of and contextualise COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Ealing. Key considerations and lessons for achieving greater vaccine and health equity are presented, followed by additional context of interest to responders within statutory authorities and the community. This brief was produced by SSHAP in collaboration with partners in Ealing Council. It was authored by Tabitha Hrynick and Santiago Ripoll and is the responsibility of SSHAP.i

‘Vaccine equity’ refers to fair and just access to vaccines for all people. Lower vaccine uptake among some groups can point to inequities which may be related to aspects of vaccination programmes, as well as to other social, economic or political factors.

Key Considerations

- Sustain, strengthen and adapt collaborative and joined-up approaches to working between local authorities, NHS, community groups and beyond. Such cooperation is essential to vaccination success in Ealing and can also be leveraged to improve health equity more broadly.

- Establish and support mechanisms for more decentralised action for vaccination and other key health and social services. These services may be more accessible and trusted by Ealing’s more vulnerable residents, including ethnic minority, migrant, and unregistered groups.

- Emphasise ‘going to’ residents, moving beyond more conventional forms of engagement such as public forums and webinars which may attract only already more engaged residents. Smaller, less visible groups in Ealing, in particular, may require more attention.

- Support community response through resources for community organisations to implement actions, facilitate two-way information flows, and meaningfully participate in decision-making. Identifying and supporting smaller groups or other less obvious, yet trusted, community actors, networks and initiatives can also increase capacity in important ways.

- Increase attention to vulnerable groups in Ealing to close vaccine and health equity gaps. This includes ethnic minorities, migrants, undocumented and digitally excluded individuals, people with disabilities, and those living in deprived areas. Tailored approaches capable of adapting to linguistic and cultural diversity and sensitive to distinct groups’ priorities and needs, are required.

- Respond to people’s multiple needs, as vaccination or other targeted public health measures may not be a priority for many in Ealing who struggle with poverty, including in-work poverty, precarious work, inadequate housing and other challenges.

- Place greater emphasis on residents’ lived experiences, perceptions and priorities (qualitative data). This information, in addition to the quantitative data that has guided response efforts, can ensure the response is more appropriate to the local context.

- Encourage and enlist support of local political leadership that recognises and represents residents across Ealing’s diverse social groups. Local leaders can support mobilisation for vaccination and other issues within local areas and advocate on behalf of them at borough level.

- Encourage greater engagement of GPs and other health professionals (e.g. pharmacies, dental clinics, alternative health providers etc.) to support vaccination and other public health and social priorities, bearing in mind their need to provide other critical services.

COVID-19 and vaccine equity in Ealing

COVID-19 in Ealing. Ealing has been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 cases and deaths, with a rate of 14,034.5 infections per 100,000 people, compared to 12,347.8 in London and 12,364 in England.1 This is related to the fact that COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted people from ethnic minority backgrounds,2–4 who make up a substantial proportion of Ealing’s population.5 Many factors have interacted to increase COVID-19 risk among these groups, including long-standing inequities in health, employment, housing, access to care and more.6 People from ethnic minority groups are, for instance, disproportionally employed in high-risk occupations (e.g. cleaning, security, public transport, etc.),7 and are more likely to struggle with access to housing. Indeed, Ealing ranks 8th among London boroughs for living in overcrowded housing – a risk factor for COVID-19 – with ethnic minority residents being disproportionately affected by this.8

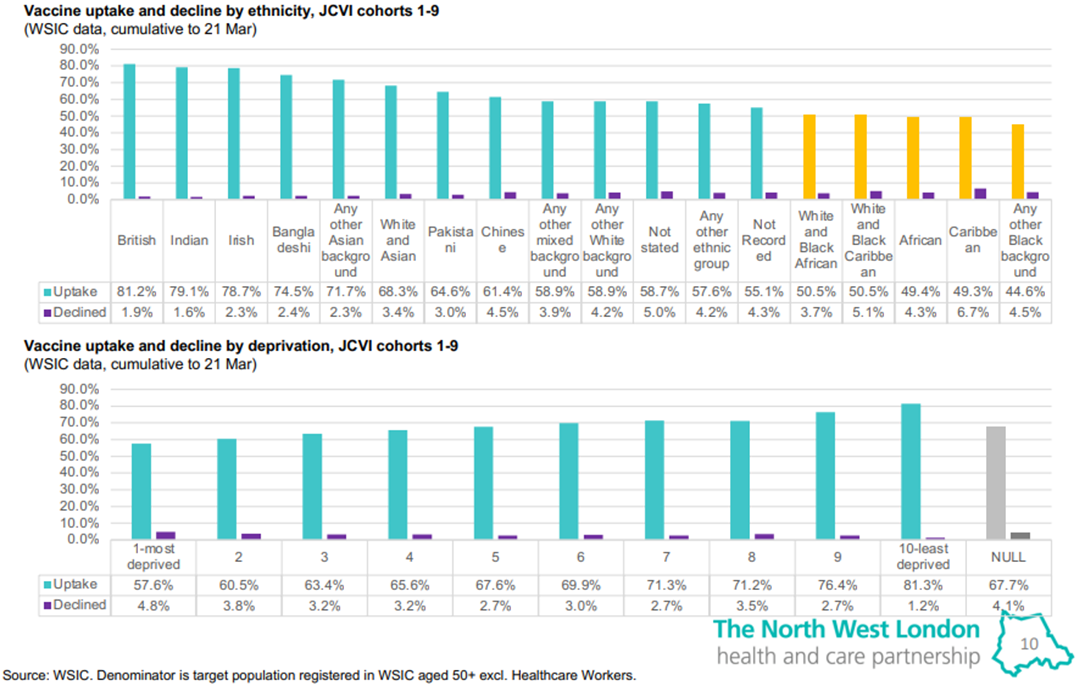

COVID-19 vaccine equity. While Ealing has achieved impressive uptake overall, disparities remain between different social groups. Uptake among the most deprived groupsii and individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds, particularly black (African and Caribbean) and mixed black backgrounds, have lagged behind their white British counterparts (see Figure 1iii), although these gaps have narrowed.9

Figure 1 COVID-19 vaccine uptake and decline rates by ethnicity and deprivation up to March 21, 2021

Figure 1 tables produced by Imperial College Healthcare Partners using Whole Systems Integrated Care (WISC) data and presented at the NWL Health and Care Partnership’s public ‘Co-production and Improvement Huddles’ for vaccine equity. Publicly available from: https://www.nwlondonccg.nhs.uk/application/files/5516/1770/2590/NWL_ICS_CoViD_Towards_Vaccine_Equity_Huddles_30.3_synthesis.pdf

Understanding what is behind these disparities is critical to addressing them. It is helpful to think of vaccine equity as comprising three dimensions: 1) confidence and trust; 2) social processes influencing motivation; and 3) accessibility.10,11 An understanding of the political, social and economic context, in particular, can help bring clarity to these dimensions in Ealing and illuminate ways to improve efforts towards vaccine and health equity.

Contextualising vaccine equity

National responses. Vaccine uptake in Ealing cannot be considered outside the context of national-level pandemic responses. Early downplaying of the crisis, delays to key public health interventions and economic support for citizens, corruption, confusing messages, stigmatising narratives and overall momentous loss of life have damaged trust in government and adjacent institutions.12–16

‘Superdiversity’. Ealing is home to a highly diverse community of people from over 170 countries. They speak different languages, practice different religions and have different migration statuses, labour market experiences, and distinct histories and experiences within the UK.5 People and groups with different backgrounds and experiences may have different levels of trust, confidence and motivation to take COVID-19 vaccines.

The ‘hostile environment’. Decades of national policies increasingly hostile towards migrants are likely to have damaged the trust of Ealing’s migrant communities in government and authorities. Policies have included increasing restrictions and costs for healthcare,17 data-sharing practices between public services and the Home Office,18,19 and dismal affairs such as the Windrush Scandal.20 Fears of incrimination or deportation on the part of vulnerable migrants, even those entitled to care, has delayed and deterred many from seeking needed support.21,22 Ealing-based Southall Black Sisters, for instance, have reported that women with insecure migration status have avoided seeking healthcare as well as domestic violence protection services due to fears of incrimination.23

Research in Hillingdon revealed that unaccompanied Congolese child asylum seekers experienced their relationship with the resource-strapped local council, which provided them with only the most basic of care, as ‘anything but a close and caring one’.24 Such experiences may reasonably bring vulnerable asylum seekers to question whether the state, including at the local level, has their best interest at heart.

Transnational links to countries of origin. Many of Ealing’s migrant groups may remain closely linked to the histories, cultures, networks and institutions of their countries/regions of origin, where differences in vaccine strategies (or other public health measures) could cause confusion about local ones. Historical events elsewhere, such as ill-fated medical trials25 or political turmoil26 might also lead some groups to mistrust authorities and health interventions.

Racism, institutional racism and xenophobia, including how these intersect with gender, class, religion and more, have undermined many ethnic minority group members’ opportunities and trust in formal authorities. Generalisations about different ethnic groups’ experiences, and one-size-fits-all approaches to their needs, can further entrench mistrust and marginalisation.

Box 3. Experiences of racism and ethnic exclusion in Ealing

-

- From 1963-1981, Ealing Council bussed only South Asian children to schools outside their local areas. This was justified as necessary to ‘racially integrate’ schools, yet families experienced the bussing as racist.27

- The Southall Black Sisters have long drawn attention to the ways in which domestic abuse services and related support have failed women from migrant and ethnic minority backgrounds in Ealing and beyond.28

- Anthropological research has suggested that some within Ealing’s Somali population may feel particularly politically unrepresented, even while they perceive other minority groups (e.g. South Asian) to be more fully represented.29

Health inequalities, such as decreasing life expectancy among the poorest, and higher rates of certain medical conditions and negative health outcomes among racialised groups in the UK, result from a wide range of bio-social factors related to deprivation and structural inequities.30–32 Even when accounting for these, some racialised health inequality gaps persist, indicating the direct role for racism in many outcomes.31,33 Many may also struggle to access, or have negative experiences with the health system when care is needed.34,35 These inequities and experiences can manifest in lower trust and engagement with health interventions.

Past research with older Indian residents in Southall revealed long delays to treatment for cataracts. Reasons included frustration with long wait times, linguistic challenges, failure of GPs to explain things or follow up on referrals, and loss of patients’ records.36

Economic inequality, precarity and austerity also play roles in limited vaccine uptake. Poverty, including in-work poverty, can mean vaccination remains a low priority for many. Rising work precarity,37 which affects Ealing disproportionately,38 can also make it difficult to take time off for vaccination. Economic inequities, long exacerbated by austerity-driven cuts to critical services39 and now the pandemic, can leave people with limited opportunities and a sense of abandonment and mistrust – especially as the state takes a seemingly sudden interest in residents’ wellbeing.

Box 5. Economic realities in Ealing

-

-

- Ealing is the 87th most deprived English local authority (out of 326). The most deprived areas are Norwood Green, Northolt West End, Southall Broadway and Southall Green.40

- 49% of Ealing’s social care workers are on zero-hours contracts (compared to 42% in London and 25% in England).41

- In 2018, 30.2% of Ealing’s workforce experienced in-work poverty compared to London’s 20.4%.42

- Unemployment disproportionately impacts ethnic minorities. In 2019, 79.2% of Ealing’s white residents, 72.7% of Indian residents, 56.2% of black residents and 46% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi residents were employed.43

-

View from the ground: challenges and enablers of vaccine equity in Ealing

Amidst the contextual realities outlined above, responders and community members have worked throughout the vaccine rollout to support uptake across the borough. The rollout in Ealing began with two mass sites, located at the town hall in New Broadway and the Dominion Centre, an arts and community centre, in Southall. Initially, Primary Care Networks (PCNs) also provided vaccination services in GP surgeries across the borough before reverting to routine services. Over time, the response adopted a more decentralised approach, running temporary pop-up sites across the borough.

At the time of writing, an impressive 76% of Ealing’s population (aged 18+) had received one dose, and 72% two doses.44 However, people we consulted suggested it had become difficult to identify the missing quarter of adults yet to receive one dose, and how best to reach them.

Challenges to vaccine equity

Many reported that only limited locally-specific data was available on the possible reasons people were not coming forward. That said, they did have some impressions, resulting from personal observations and valuable community engagement efforts. Many of the factors mentioned relate to the confidence, trust and social processes dimensions of vaccine equity, and included:

- Fear over vaccine safety. This included fear of needles, severe side effects, and even death.

- Fear of vaccines linked to mistrust. Mistrust and fears about the true intentions of pharmaceutical firms, medical actors and authorities were exacerbated in some cases by past events elsewhere25 and the actions of national actors (e.g. Matt Hancock suggesting black people should be vaccinated first).

- Mistrust due to exclusion and abandonment. Among some, there may be a sense that authorities have not previously demonstrated care about citizens, and yet are now pushing them to seek vaccination.

- Fear of incrimination or deportation on the part of undocumented migrants. This became powerfully evident when they turned up for vaccination in large numbers following efforts by the council and NHS to reassure this population they would not need to provide any identifying information.

- Information delays. It was hypothesised that perceived delays on the part of local authorities in sharing key information with Ealing’s citizens, has damaged the trust of some residents.

- Assumptions about trusted actors. Some worried whether residents actually trusted the community leaders and groups engaged by local authorities to promote vaccination.

- Diasporic links. The strong ties of some social groups to leaders, networks and institutions of their countries of origin were also mentioned. For instance, a Somali group in Ealing insisted on endorsement of COVID-19 vaccines by a specific Somali Islamic scholar.

Council teams prepared to promote a home-based/online alternative to Taraweeh prayers, which are normally done at a mosque, after the national British Islamic Medical Association suggested this would be acceptable for Muslims. Community engagement leads intervened, recognising that BIMA was not trusted by local Muslim residents – who perceived it to overly compromise the faith – thus demonstrating the critical role of community engagement specialists.

In addition to these factors, others mentioned were more linked to supply-side issues and their impact on accessibility of vaccines:

- Short-lived GP engagement. Primary Care Networks across Ealing initially ran decentralised vaccination sites alongside the two mass sites but had to stop to provide other critical health services. While important, this decreased residents’ options and increased the distance many would have to travel to get vaccinated.

- Uneven coverage across the borough. This resulted from initial – and well-placed – concern that efforts should focus on Southall due to its many undocumented and ethnic minority residents. Some felt other vulnerable areas (e.g. Acton, Greenford, Northolt) had been relatively underserved.

- Timing of vaccination availability. Timeframes during which vaccination is usually available have not suited the schedules of many workers and carers in Ealing.

- The lack of appropriate and affordable transportation options for people to get to vaccination sites which may be far from them, has impeded vaccination for many.

- A focus on overall numerical targets. Due to pressure, there was a focus on achieving quantitative targets for vaccination prevailed over prioritising reaching smaller yet vulnerable ethnic minority, migrant and unregistered groups, which can require additional planning and resources.

- Recognition not leading to action. Even when it was recognised more tailored, resource-intensive approaches were needed to reach some groups and residents, action was not always taken.

Additional factors related to the wellbeing and capacities of responders themselves:

- Staff overwork and burnout. Despite steadfast commitment, many of those working on the rollout were at risk of burnout, thus also endangering efforts to ensure vaccine equity.

- Limited support/communication from national level. This sent teams scrambling to implement changes with hours’ notice, increasing stress and potentially reducing chances for success.

- Logistical challenges. These included transporting and knowing how much vaccine would be necessary for a pop-up site, or having appropriate vaccines on hand (e.g. for under-40s and those preferring specific vaccines), which could also influence accessibility.

Enablers of vaccine equity

Despite the many challenges to local vaccine equity, responders made efforts to narrow gaps in uptake, including through learning along the way. Some of the strategies local actors felt improved vaccine equity are listed below:

- Shift from centralised to decentralised modes of delivery. While mass vaccination sites have reached many, numerous residents from more vulnerable and marginalised social groups have been better served by temporary pop-up sites in more accessible or comfortable locations (e.g. places of worship, local schools, pharmacies, supermarket parking lots etc.).

- Communicating that registration/identification is not necessary. After this was clarified, many residents, particularly from unregistered groups (especially undocumented migrants, but also others preferring anonymity) arrived for vaccination.

- Community engagement (CE). Although the council’s CE team is small with few resources, their engagement with local community leaders was seen as highly valuable in supporting information dissemination through local networks, while also feeding information about community concerns to responders. Public webinars hosted by local authorities and community organisations, as well as engagements with smaller specific groups, were also seen as critical, although there were still concerns that many less engaged residents remained reached.

Authorities initially hesitated to meet with a local Somali group due to the small number of attendees. The group also requested the presence of a Somali Islamic scholar. Although challenging to arrange, the group came away from the meeting feeling much more confident in COVID-19 vaccines despite their initial hesitance. This illustrates that resource-intensive engagement is often necessary if responders are serious about vaccine equity and reaching smaller, vulnerable groups within a broader, ‘superdiverse’ community.

- Active listening to people on the ground. Although mainly ad hoc (e.g. conversing with people at vaccination sites), this strategy revealed key challenges faced by residents, and thus opportunities to improve response – such as supporting people with travel. However, some people felt frustrated when, after their repeated consultation, they did not see how the information they provided was used and whether it led to changes in the vaccine rollout.

- Collaborative, flexible and joined-up working. Collaboration and regular interaction between and within the council and CCG was mentioned as critical. Despite challenges, the increased engagement led to higher quality response, appreciation for the contributions of different teams, and opportunities for learning.

There were also opportunities for regional learning through the NWL Co-production and Improvement Huddles for Vaccine Equity.45 In these online weekly sessions, council teams, councillors, NHS professionals, community groups and residents shared challenges, strategies and opportunities to link in with initiatives across the region.

- Supporting/working with community groups. Community groups which were recognised as highly agile, responsive and keen to support local vaccination efforts, was considered critical. However, concerns about compensating them for their time have been raised, particularly for smaller and more informal organisations.46

In North Kensington, local NHS actors and trusted community organisations, including the Al-Manaar Muslim Cultural Heritage Centre, which played a critical role in the wake of the Grenfell disaster, partnered to launch the ‘Community Immunity’ initiative. It included webinars, pop-up vaccination sites, a ‘vaxi taxi’, a phone line to help people book appointments, and initiatives to provide vaccination and more holistic support to rough sleepers.

- Taking a data driven approach. Responders have relied on quantitative vaccination uptake data to guide their efforts, for instance, increasing activities in Acton after it became clear that uptake here was lower. However, more emphasis on qualitative data, which contextualises and explains the numbers, is needed.

Conclusion

This brief has aimed to contextualise COVID-19 vaccination in Ealing – and in particular, the persistent disparities in uptake between different social groups – to reveal lessons for local actors aiming to achieve greater vaccine equity locally. By appreciating Ealing’s social, economic and political past and present, and recognising the challenges and successes of the COVID-19 vaccination rollout to date, a number of key considerations emerge. Broadly, these include a need to integrate sensitivity to the distinct needs and concerns of Ealing’s diverse social groups; to sustain collaborative working across teams, organisations and sectors; and to build trust with and meaningfully engage citizens – especially the most vulnerable groups. These key considerations are further detailed at the beginning of this brief, and are relevant not just to achieving greater COVID-19 vaccine equity, but to health equity in Ealing and NWL more broadly.

ENDNOTES

i This brief is an abbreviated version of a longer and more detailed review which can also be found on the SSHAP website.

ii ‘Deprivation’ as cited in this brief generally refers to those living in the most deprived neighbourhoods in England as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), an official measure which takes into account income, employment, education, skills and training, health and disability, crime, barriers to housing services, and living environment.

iii Figure 1 reflects uptake by JCVI (Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation) cohorts 1-9 which includes all those aged 50 and up, as well as all clinically extremely vulnerable, and at-risk groups in the UK.

REFERENCES

- Ealing Covid-19 Dashboard. (2021). https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiN2E2ZTVkNjQtYzQ0Yy00MWMzLTgyNTQtNWRhMDJhYjNhOTVlIiwidCI6IjAxM2E4YzQzLTgyODctNGM4Yi04NzhiLTEzMWUzMGNkYjlmMyIsImMiOjh9&pageName=ReportSection5e3167bd736ca021bc5a

- Kontopantelis, E., Mamas, M. A., Webb, R. T., Castro, A., Rutter, M. K., Gale, C. P., Ashcroft, D. M., Pierce, M., Abel, K. M., Price, G., Faivre-Finn, C., Spall, H. G. C. V., Graham, M. M., Morciano, M., Martin, G. P., & Doran, T. (2021). Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes by region, neighbourhood deprivation level and place of death during the first 30 weeks of the pandemic in England and Wales: A retrospective registry study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100144

- PHE. (2020). Beyond the Data: Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on BAME Communities (p. 69).

- ONS. (2021). Updating ethnic contrasts in deaths involving the coronavirus (COVID-19), England: 24 January 2020 to 31 March 2021. Office for National Statistics (ONS). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/updatingethniccontrastsindeathsinvolvingthecoronaviruscovid19englandandwales/24january2020to31march2021#difference-between-the-risk-of-death-involving-covid-19-by-ethnic-group-in-the-first-and-second-waves-of-the-pandemic

- Ealing Council. (2020). Equalities Needs Assessment (UK). Ealing 1.12 WISP Migration. https://www.ealing.gov.uk/downloads/download/2043/equalities_needs_assessment

- SAGE. (2021). Interpreting differential health outcomes among minority ethnic groups in wave 1 and 2. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-ethnicity-subgroup-interpreting-differential-health-outcomes-among-minority-ethnic-groups-in-wave-1-and-2-24-march-2021

- Women and Equalities Committee. (2020). Unequal impact? Coronavirus and BAME people. House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmwomeq/384/38402.htm

- PHE. (n.d.). Overcrowded households—Ealing. Public Health England. Retrieved 10 June 2021, from https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/search/overcrowding#page/4/gid/1/pat/6/ati/101/are/E09000009/iid/90416/age/-1/sex/4/cid/4/tbm/1

- North West London Health and Care Partnership. (2021, March). Towards vaccine equity through reducing variation in NWL CoViD-19 vaccination uptake. https://www.nwlondonccg.nhs.uk/application/files/5516/1770/2590/NWL_ICS_CoViD_Towards_Vaccine_Equity_Huddles_30.3_synthesis.pdf

- MacDonald, N. E., & the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

- WHO. (n.d.). Increasing Vaccination Model. Retrieved 14 July 2021, from https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/Increasing_Vaccination_Model-WHO.PDF?ua=1

- Dibb, S. (n.d.). Where the UK government is going wrong in its coronavirus messaging, according to a marketing expert. The Conversation. Retrieved 9 June 2021, from http://theconversation.com/where-the-uk-government-is-going-wrong-in-its-coronavirus-messaging-according-to-a-marketing-expert-146783

- Independent SAGE. (2021). Covid-19: Racialised stigma and inequalities. The Independent SAGE Report 33. The Independent Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Stigma-and-Inequalities_16-12-20_D6.pdf

- Ham, C. (2021). The UK’s poor record on covid-19 is a failure of policy learning. BMJ, 372, n284. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n284

- Paton, C. (n.d.). ‘We did everything we could’: An account of toxic leadership. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3264

- West-Oram, P. (2021). Solidarity is for other people: Identifying derelictions of solidarity in responses to COVID-19. Journal of Medical Ethics, 47(2), 65–68.

- Shahvisi, A. (2019). Austerity or Xenophobia? The Causes and Costs of the “Hostile Environment” in the NHS. Health Care Analysis, 27(3), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-019-00374-w

- Bradley, G. M. (2018). Care Don’t share: Hostile environment data-sharing—Why we need a firewall between essential public services and immigration enforcement. Liberty. https://www.libertyhumanrights.org.uk/issue/care-dont-share/

- Papageorgiou, V., Wharton-Smith, A., Campos-Matos, I., & Ward, H. (2020). Patient data-sharing for immigration enforcement: A qualitative study of healthcare providers in England. BMJ Open, 10(2), e033202. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033202

- Wardle, H., & Obermuller, L. (2019). “Windrush Generation” and “Hostile Environment”: Symbols and Lived Experiences in Caribbean Migration to the UK. Migration and Society, 2(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.3167/arms.2019.020108

- Doctors of the World. (2017). Deterrence, delay and distress: The impact of charging in NHS hospitals on migrants in vulnerable circumstances [Research Briefing]. Doctors of the World. http://www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/import-from-old-site/files/Research_brief_KCL_upfront_charging_research_2310.pdf

- MedAct, Migrants Organise, & New Economics Foundation. (2020). Patients not passports: Migrants’ access to healthcare during the coronavirus crisis. https://www.medact.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Patients-Not-Passports-Migrants-Access-to-Healthcare-During-the-Coronavirus-Crisis.pdf

- Imkaan. (2020). The Impact of the Dual Pandemics: Violence Against Women and Girls and COVID-19 on Black and Minoritised Women and Girls [Position paper]. https://rapecrisis.org.uk/media/2253/dual-pandemics-imkaan-report.pdf

- Wahlström, Å. M. C. (2009). Friends, Corporate Parents and Pentecostal Churches: Unaccompanied Asylum Seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo in London [Brunel University]. https://bura.brunel.ac.uk/bitstream/2438/4507/5/FulltextThesis.pdf.txt

- Smith, D., & Africa. (2011, August 12). Pfizer pays out to Nigerian families of meningitis drug trial victims. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/aug/11/pfizer-nigeria-meningitis-drug-compensation

- Hamilton, O. (2021, March 13). Poles apart: Why the Polish community doesn’t want the vaccine | The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/poles-apart-why-the-polish-community-doesnt-want-the-vaccine

- Bebber, B. (2015). “We Were Just Unwanted”: Bussing, Migrant Dispersal, and South Asians in London. Journal of Social History, 48(3), 635–661. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shu110

- Siddiqui, H., & Patel, M. (2010). Asian Minority women, domestic violence and mental health: The experience of Southall Black Sisters. In C. Itzin, A. Taket, & S. Barter-Godfrey, Domestic and Sexual Violence and Abuse: Tackling the Health and Mental Health Effects. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/suss/detail.action?docID=592912

- Scuzzarello, S. (2015). Narratives and Social Identity Formation Among Somalis and Post-Enlargement Poles: Narratives and Identity among Somalis and Poles. Political Psychology, 36(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12071

- Marmot, M. (2020). Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. Bmj, 368.

- Razai, M. S., Kankam, H. K. N., Majeed, A., Esmail, A., & Williams, D. R. (2021). Mitigating ethnic disparities in covid-19 and beyond. BMJ, 372, m4921. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4921

- Knight, M., Bunch, K., Tuffnell, D., Jayakody, H., Shakespeare, J., Kotnis, R., Kenyon, S., & Kurinczuk, J. (2017). Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care-Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2014-16. University of Oxford: Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit.

- Raisi-Estabragh, Z., McCracken, C., Bethell, M. S., Cooper, J., Cooper, C., Caulfield, M. J., Munroe, P. B., Harvey, N. C., & Petersen, S. E. (2020). Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25(OH)-vitamin D status: Study of 1326 cases from the UK Biobank. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 42(3), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa095

- Phillimore, J. (2011). Approaches to health provision in the age of super-diversity: Accessing the NHS in Britain’s most diverse city. Critical Social Policy, 31(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018310385437

- Bradby, H., Lindenmeyer, A., Phillimore, J., Padilla, B., & Brand, T. (2020). ‘If there were doctors who could understand our problems, I would already be better’: Dissatisfactory health care and marginalisation in superdiverse neighbourhoods. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(4), 739–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13061

- Patel, D., Baker, H., & Murdoch, I. (2006). Barriers to uptake of eye care services by the Indian population living in Ealing, west London. Health Education Journal, 65(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896906067777

- Booth, R. (2016, November 15). More than 7m Britons now in precarious employment. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/nov/15/more-than-7m-britons-in-precarious-employment

- GMB. (2017). Insecure: Tackling precarious work and the gig economy. https://gmb.org.uk/sites/default/files/GMB17-InsecureWork.pdf

- Stuckler, D., Reeves, A., Loopstra, R., Karanikolos, M., & McKee, M. (2017). Austerity and health: The impact in the UK and Europe. European Journal of Public Health, 27(suppl_4), 18–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx167

- Stewart, R., & Ahlawat, R. (2015). Deprivation in Ealing. A Report on the English Indices of Deprivation 2015. Ealing Council. https://www.ealing.gov.uk/downloads/download/1015/indices_of_deprivation_for_ealing

- Skills for Care. (2020). A summary of the adult social care sector and workforce in Ealing 2019/20. Skills for Care. www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/publications/Topics/COVID-19

- Oxford Economics. (2020). How might coronavirus impact the West London economy? Oxford Economics. http://democracy.lbhf.gov.uk/documents/s113727/Annex%20A%20-%20How%20might%20coronavirus%20affect%20the%20West%20London%20Economy%20Oxford%20Economics.pdf

- ONS. (2020). Employment Rates by Ethnicity. https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/employment-rates-by-ethnicity

- UK Government. (2021). UK Coronavirus Dashboard. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/download

- North West London Clinical Commissioning Groups. (n.d.). Vaccine equity – work with us. Retrieved 12 November 2021, from https://www.nwlondonccg.nhs.uk/coronavirus/vaccine-equity-work-us

- Diriye, S. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Ealing’s BAME Communities. GOSAD. https://www.gosad.org.uk/sites/gosad.hocext.co.uk/files/2020-09/THE%20IMPACT%20OF%20COVID-19%20ON%20EALING%27S%20BAME%20COMMUNITIES.pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This brief has been written by Tabitha Hrynick ([email protected]) and Santiago Ripoll.

We also wish to acknowledge expert input from others. Expert review was provided by: Maddy Gupta-Wright, Public Health team at London Borough of Ealing; Dr Ellen Schwartz, Immunisation lead for the Association of Directors of Public Health in London (ADPHL); Dr Nikita Simpson, London School of Economics; Hayley MacGregor, Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and SSHAP; and Melissa Parker, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and SSHAP.

Additional acknowledgements are also extended to: Christopher Jack, Janpal Basran, Angela Dodwell, Paul Najsarek, Vijay Tailor, Steve Curtis, Matt Van Mol-Jones, Tan Afzul, Evelyn Gloyne, Rajiv Ahlawat, Ryan Ashlee, Ian Smith, Chrissy Leonard, Gary Redhead, Manpreet Bains, Neha Unadkat, Jack Butler, Cheryl Curling, Anna Bryden and Violet Mendonca.

CONTACT

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Olivia Tulloch ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and Wellcome Grant Number 219169/Z/19/Z The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of IDS, Anthrologica or LSHTM.

KEEP IN TOUCH

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Hrynick, T. and Ripoll, S. (2021). Key Considerations: Achieving COVID-19 Vaccine Equity in Ealing and North West London. Social Science In Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) DOI: 10.19088/SSHAP.2021.041

© Institute of Development Studies 2021

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode