A number of concerns and misgivings lie at the heart of public opinion in Africa, faced with the future vaccination against Covid which is already well underway in Europe, the USA, Russia, China, and India¹.

Such concerns and misgivings do exist in Northern countries as well. They are based in part on various scandals which have been blamed on the pharmaceutical industry (such as the drug Mediator), and on its bad reputation (“big pharma”), owing to its business practices, the powerful and constant pressure it is able to exert on the media and politics, and the number of doctors whose silence and complicity it has bought. The mistrust is made worse by the conspiracy theories which circulate widely on social media, despite how preposterous these can be (for example that Covid 19 doesn’t exist, or has been created by Bill Gates to inoculate humanity with electronic components under the pretext of vaccination…).

In Africa, these concerns and misgivings also have a strong presence, but there are additional factors which feed into them. The unsettled scores of French colonisation are making a comeback. Colonial medicine, for example, long associated with the despotism of the occupying forces, has not left behind solely positive memories (the case of Lomidine studied by Lachenal is one such example). Widespread post-colonial mistrust of western countries, accused of wanting to rule and pillage Africa under the guise of helping it, also plays a part and is aggravated by the unbalanced exchange of raw materials and manufactured goods, the arrogance displayed by French and American leaders, decades of French influence and control, as well as certain clandestine molecular testing which at one point was using Africans as guinea pigs ( the novel “The Constant Gardener” by John Le Carré, and the subsequent film adaptation, are in their own way a testament to this).

Against this background of very real trauma and justified mistrust, Covid 19 becomes the subject of uncontrollable rumours, which take no notice any more of proven facts and which move further and further away from scientific knowledge. Health, as we know, is a particularly rich breeding ground for generating new beliefs and, throughout the world, experimental medicine is often neglected in favour of a wide variety of magic potions and miracle cures. In Africa Professor Raoult, who now promotes anti-vaccine rhetoric and has an impressive following, and the widespread prescription of hydroxychloroquine in towns and cities², are good examples of this. We should remember that, in rural settings, anti-vaccination rumours were spread regularly and widely, sometimes on religious grounds, for example accusing the West of wanting to sterilise African women under the guise of vaccinating them against meningitis.

Social media amplifies all these rumours by constantly spreading unproven, distorted, false, and alarmist information, pointing to underground conspiracy theories, scaremongering, fuelling suspicions, and disseminating paranoia.

So, given this misinformation which in Africa is circulating widely, we believe it is necessary to establish calmly what science does and doesn’t know about the vaccination against Covid 19, so as to provide accurate information and enable serious discussion about this topic. This text therefore is not a personal research article. Here we are summarising, in a convergent manner, the knowledge brought to us by the international scientific press and which is the subject of widespread consensus amongst specialists (virologists, epidemiologists, infectious disease specialists) worldwide.

Double blind randomised clinical trials are at the foundation of most of the remarkable progress of modern medicine, which increasingly shows itself to be “evidence-based”. They represent the only way to determine rigorously the effectiveness or the safety of a molecule, drug, or vaccine. Today (far more than previously) they are one of the most controlled and clearly defined areas of the world of biomedicine. The certification procedures involved in the testing process (phase 1, phase 2, phase 3, phase 4) and in placing drugs on the market have become particularly rigorous in high-income nations. Such procedures have been observed for the main anti-Covid vaccines currently available (one British and two American vaccines; there is also a Russian vaccine and a Chinese vaccine, but we don’t have much accurate information concerning them; a number of other vaccines are now undergoing testing). The phase 3 trials, each one carried out on several thousand people, have all taken place and particularly in those countries most affected (very few have been done in Africa). Phase 4, the follow-up of those people vaccinated (pharmacovigilance), is underway, in accordance with the prescribed procedures, in every country where the vaccine is beginning to be administered.

The speed with which the vaccine against Covid 19 has been developed is remarkable (one year as opposed to three or four). It therefore gives rise to questions and fears. However the certification procedures have been observed; it can be put down to an achievement in biomedicine, and not dangerous and shoddy research. This feat is due to an immense and unprecedented mobilisation of manpower and financial resources (governments of Northern countries have all provided huge funding to laboratories, who of course are hoping to make a fortune, but who must also be accountable to these Countries and work under the strict supervision of numerous international experts). It is due as well to the existence of sound prior knowledge about coronavirus (the family of which Covid 19 is a part) and about the recent development of new biological techniques (using messenger RNA) adopted for the first vaccines put on the market.

There are however two weak links, written about extensively in the specialised press. On the one hand the phase 3 trials were held over a much shorter period of time than normal (a few months rather than a year), which does not allow for the detection of possible adverse effects in the medium term. That being said, with vaccines the vast majority of adverse effects appear in the first few months. However we cannot dismiss the possibility of adverse affects occurring beyond this. Furthermore, those people who have participated in the trials have not always been totally representative of the general population: few older people have been included for example. We cannot dismiss the possibility that the effectiveness of the available vaccines or their adverse effects will vary depending on factors which have not yet been sufficiently tested.

In addition, there are still many unknowns. The lasting effectiveness of the vaccine is one of them: we still don’t know for how many months it protects against Covid 19. Similarly, we still don’t know if it will be effective against significant mutations of the virus. As is the case with many vaccines, minor or major allergic reactions can occur in certain subjects. Finally, even if it is determined that the messenger RNA vaccines do effectively protect those people vaccinated against the effects of Covid 19, we still don’t know for certain whether they prevent the transmission of the virus by these vaccinated people in any significant way. More generally speaking, as is the case with any genetic technique, the messenger RNA genetic technique does sometimes give rise to concerns, but for the specialists, these medical techniques represent the future of medicine and they will be employed more and more.

Despite these unknowns, and given the high morbidity and mortality rates caused by Covid 19 for those populations at risk, it is absolutely essential that they be vaccinated. The risk of serious complications or even death for those individuals suffering from severe forms of Covid 19 are infinitely higher than the (relatively low) risk of adverse effects in the event of vaccination. Similarly, the serious consequences of a spontaneous development in the epidemic until such time as collective immunity is achieved far surpasses the problems posed by a mass vaccination programme which should enable us to reach that collective immunity far quicker and with far fewer deaths. In other words, both on an individual and on a collective level, vaccination is highly desirable on a worldwide scale. The benefit-to-risk ratio weighs heavily in its favour.

Even though Africa, relatively speaking, has been spared when compared with the rest of the world, it is not protected from a second, more serious wave (as is already the case in Morocco or Mali). Although its population is younger and therefore less likely to develop serious forms of the disease, there are many individuals at risk (high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes), and older people are especially vulnerable, particularly given that protective measures are generally very rarely observed. There are of course fewer deaths in Africa when compared with Europe (the numbers reported however are far below the actual figures), but each death is one too many, and the number is going to increase further though these deaths are avoidable in the future thanks to the vaccines. Malaria does indeed kill many more people than Covid 19, but this is no reason to abandon potential victims of Covid to their fate.

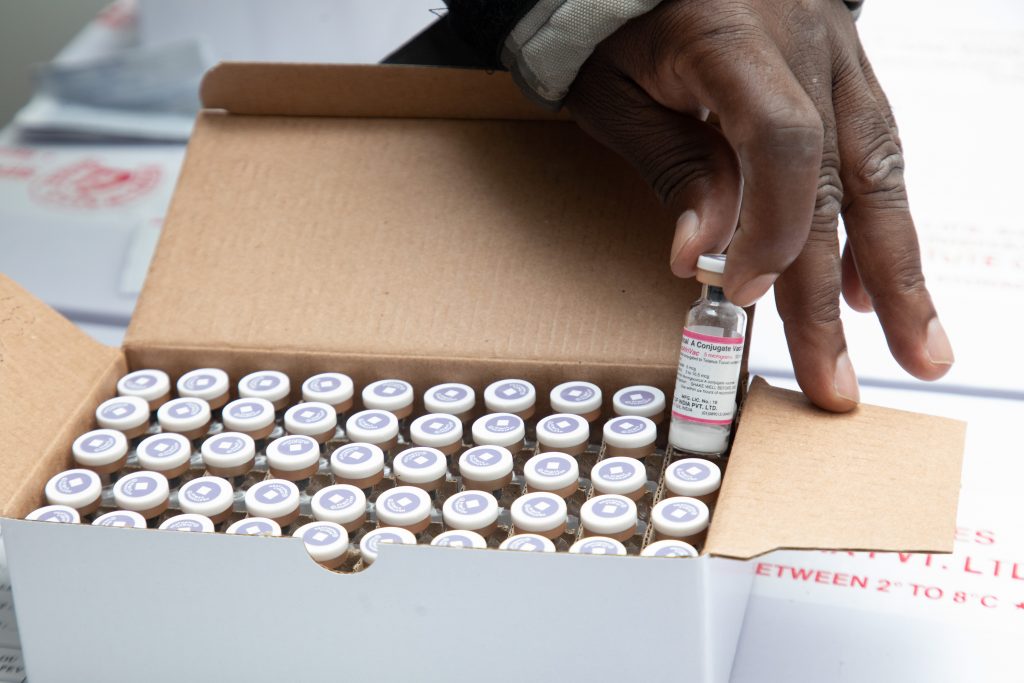

The vaccines which are to be administrated in Africa are the same as those being used in developed countries. Two distribution networks are currently being set up. One of them, Covax, brings together various international institutions (headed by the Gavi Fund, the WHO, the European Union, and the Bill Gates Foundation) and as of now is starting to purchase the British vaccine so as to distribute it using subsidies (in whole or in part) to healthcare systems in Africa (the British vaccine has the advantage of being cheaper and can be stored at room temperature). Other vaccines will soon be available as well, each with its own specific characteristics. On the other hand, China and Russia have started to make their vaccines available to countries in Africa under terms which have yet to be fully determined. The geopolitical motives and health considerations will be interwoven here. But in any event, free and rapid access for all the peoples of Africa to an effective vaccine against Covid 19 is still far from guaranteed: it is a cause that we must advance consistently.

Vaccination in Africa will not be an easy task. The healthcare systems are fragile and poorly equipped, and rural areas are often cut off. It will be necessary to vaccinate adults whereas current measures mainly target children, the populations are (not without good reason) wary of government instructions and avoid healthcare facilities, Covid 19 is not a fear belonging to everyday life (in general it is less virulent, confused with a number of acute respiratory infections, severely under-detected for lack of mass testing, often asymptomatic, and still perceived, wrongly, as a disease of the West).

Only the Departments of Health in the countries concerned are in a direct position to devise a strategy for vaccination which is appropriate for each local setting. There are a number of options and possible ways forward which cannot be imposed from outside. International support (both financial and technical) is of course vital, but should not under any circumstances replace expertise on a national level which, conversely, must be developed. Similarly, pharmacovigilance (phase 4) should be undertaken by the local healthcare systems, and we should support the launch of exhaustive vaccine research by local laboratories and the monitoring of the fight against the epidemic by African researchers in social sciences. Vaccination, pharmacovigilance, and research: it is all much more than simply harnessing resources for Covid 19, but is actually an opportunity, through the fight against this epidemic, to strengthen healthcare systems as a whole in their various roles and to fight against all diseases. The goal must be to enable a synergy of vaccinations rather than a competition, by seeking to improve the levels of both curative and preventative care.

In the face of these fears, rumours, and doubts, it is absolutely crucial that we try to convince our colleagues and those close to us of the advantages of vaccination, until any medicine becomes available: it will help to avoid a huge number of deaths. We should also remember just what humanity (and Africa) owes to vaccines. Yellow fever, measles, meningitis, polio, cholera: how many millions of lives have been spared? This is something we must never forget!

Jean-Pierre OLIVIER de SARDAN

Researcher at LASDEL, Associate Professor at the Abdou Moumouni University (Niger)

Emeritus Director of Research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (France)

- I would like to thank my colleagues who have provided me with their comments and suggestions for a first version of this text: Aïssa Diarra, Alice Desclaux, Fred Eboko, Richard Fardon, Frédéric Le Marcis, Elisabeth Paul, Louis Pizzaro, Laurent Vidal.

- Randomised clinical trials carried out on hydroxychloroquine have proven beyond any doubt that this molecule has no therapeutic effects on Covid 19.