This brief explains youth perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination and outlines key considerations for engaging with and building trust among young people living in Ealing, London. Within the category of ‘young people,’ there are differences in vaccination based on age and ethnicity. This brief is based on research, including a review of the literature and in-depth interviews and focus groups with 62 youth across Ealing to contextualise youth perspectives of COVID-19 vaccination and highlight themes of trust/distrust. We contribute ethnographic and participatory evidence to quantitative evaluations of vaccine roll-out.

Key considerations for addressing youth distrust regarding the COVID-19 vaccine are presented, followed by additional regional context. This work builds on a previous SSHAP brief on vaccine equity in Ealing.1 This brief was produced by SSHAP in collaboration with partners in Ealing. It was authored by Megan Schmidt-Sane (IDS), Tabitha Hrynick (IDS), Jillian Schulte (Case Western Reserve University), Charlie Forgacz-Cooper (Youth Advisory Board), and Santiago Ripoll (IDS), in collaboration with Steve Curtis (Ealing Council), Hena Gooroochurn (Ealing Council), Bollo Brook Youth Centre, and Janpal Basran (Southall Community Alliance), and reviews by Helen Castledine (Ealing Public Health), Elizabeth Storer (LSE) and Annie Wilkinson (IDS). The research was funded through the British Academy COVID-19 Recovery: USA and UK fund (CRUSA210022). Research was based at the Institute of Development Studies. This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS FOR YOUTH ENGAGEMENT

National-level policymakers

- Recognise that vaccination decision making is a complex and ongoing process rooted in young people’s political-economic and social experiences. Good vaccination information alone will not necessarily inspire someone to act on it, and the decision to avoid vaccines is not always based on a lack of information.

- Vaccination may not be a priority for young people experiencing poverty. Vaccine benefits should be articulated in ways that are relevant to their lives and can become persuasive and positive narratives, e.g. of keeping young people safe in their risky work environments or at school.

- Acknowledge public anxieties and uncertainty over COVID-19, including information about vaccines. Clear and consistent messaging is needed and can enhance transparency. This should include acknowledgement of what is not known or uncertain, as omitting such information can be detrimental and arouse suspicion.

- The vaccine programme is an opportunity to build trust and confidence in government services more widely, including public health. People are more likely to trust governments that are able to deliver citizens the services they need, in equitable ways.2 When possible, improve access, quality and timeliness of public services, and responses to citizens’ feedback.2 Use the vaccine campaign as a springboard to support equity in public service delivery to minoritised groups.

- Increase funding for local governments, including funds earmarked for youth services and opportunities. Youth-friendly spaces can make available life-saving services and support that will enable them to flourish. Fully supported youth services can also work to build trust between government and young people.

- Consider ways to improve public awareness of COVID-19 vaccine safety. Given the speed at which COVID-19 vaccines were developed, it is important for national government to emphasise that no regulatory corners were cut and that vaccines were developed based on extensive prior research.

Local public health officials

- Engage young people in decision-making processes through consultations and community-based dialogues to design vaccination or other public health programmes to ensure their perspectives and priorities are integrated.

- Acknowledge low trust in national government among youth and emphasise the independence of public health and medical providers working on COVID-19 from other governmental institutions, including police.

- Build more comprehensive and accessible social media campaigns to disseminate information to youth. Utilise social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, and work through locally well-known individuals.

- Train and engage youth peer leaders. Peer leaders or ‘vaccine champions’ could include young people who can engage others through youth services and schools on vaccination and public health.

- Shift the discourse around why young people should get vaccinated. COVID-19 was portrayed as a disease affecting the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions. Furthermore, vaccines were not initially available for young people. This created confusion which requires concerted effort to overcome. Also, telling most young people to get vaccinated for their own health may not resonate with experiences of mild COVID-19, or the perceived idea that ‘natural immunity’ is a substitute for vaccination. Emphasise that young people can get vaccinated to prevent symptoms associated with Long COVID, and to protect vulnerable family members.

- Publicise the fact that young people over 16 do not need parental consent for vaccination in the UK. Some young people have the misconception that they need parental consent to get vaccinated. Information about the age of vaccine consent can be easily shared via news, schools/teachers, and social media.

- Provide support to mentors, teachers, and parents to engage in positive conversations with young people about vaccination. Information should be tailored to different age groups as older teenagers have been found to be more vaccine hesitant compared to younger youth. This could also include template lesson plans for teachers to teach news and media literacy skills so that young people are equipped to discern between credible information and misinformation.

- Young people are less likely to engage with public health or other authorities if they feel socially excluded. Recreation and youth centres play a vital role in young people’s lives, but funding cuts have led to reduction in their availability. There is a need for more youth-friendly spaces and other opportunities for young people to share their concerns and their voices. Improving public health engagement more broadly should include support for this, including through cross-sector working across public health, youth services and non-profits.

- Advocate with local government leaders for increased funding for, and engagement with youth services as a critical space in vulnerable youth’s lives. Youth services, including youth centres, are quite literally, life-saving for many youth. Many vulnerable young people in this study described how local youth workers were like a second parent to them and had connected them to vital services such as resume writing support, or to job opportunities. These critical workers and youth centres must be better funded and supported. Young people also need schemes and benefits that support them to identify and pursue positive career paths.

Youth services

- Engage in listening sessions with youth to understand how remote schooling and disruptions to their education impacted how they relate to adult policy makers, including in public health. Young people were affected more by COVID-19 lockdowns and remote school than by the virus itself. If appropriate, consider using these sessions to answer questions about COVID-19 vaccination or refer youth to health services.

- Young people’s negative experiences with other authorities, like police, colour their views of authorities in general. Facilitate dialogue between young people living in deprived areas and local police on ‘neutral’ territory and with cross-sector involvement, including key community partners, youth workers, and parents. These dialogues could be a space for listening to young people’s experiences with police and identifying solutions to end harmful policing practices. Community organisations and leaders can act as good-faith mediators to help design dialogue sessions, and ensure they meaningfully involve young people rather than becoming tick-box exercises.

COVID-19 CASES & VACCINATION RATES IN EALING

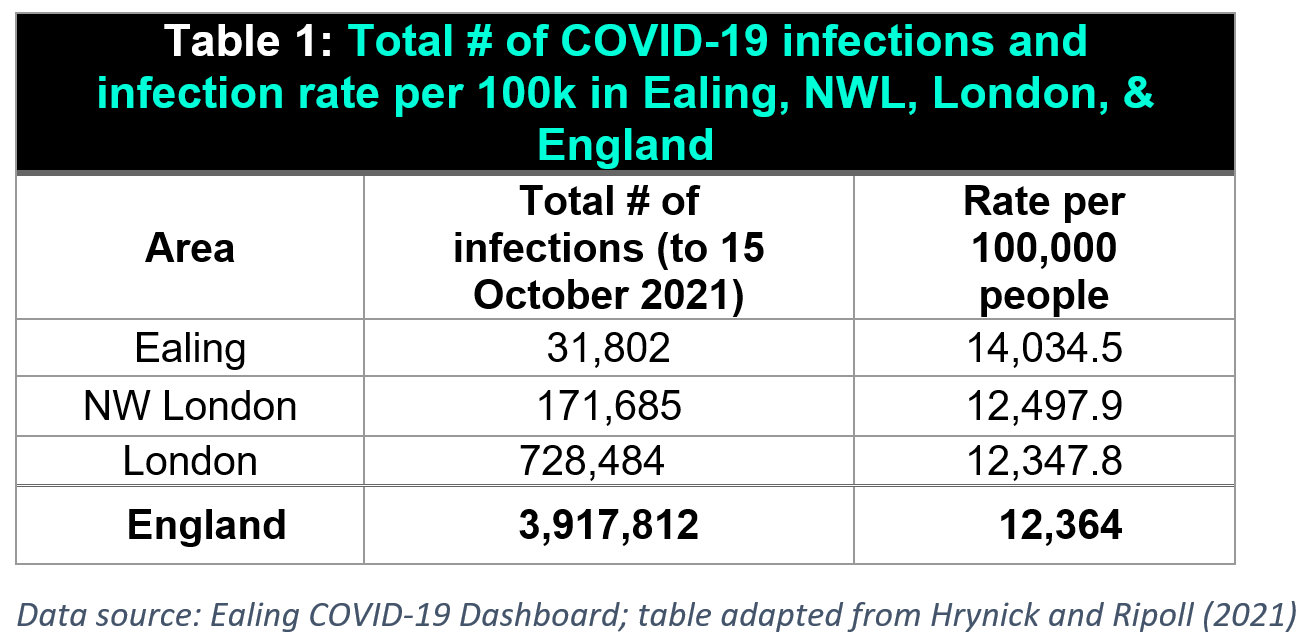

COVID-19 case rates in Ealing. The borough of Ealing is in the northwest quadrant of London (outer boroughs), in the UK. It is home to about 350,000 residents, nearly half of whom were born abroad in over 170 different countries.3,4 During the pandemic, Ealing has been disproportionately impacted by the virus, with higher infection rates than neighbouring areas and England overall (see Table 1).1

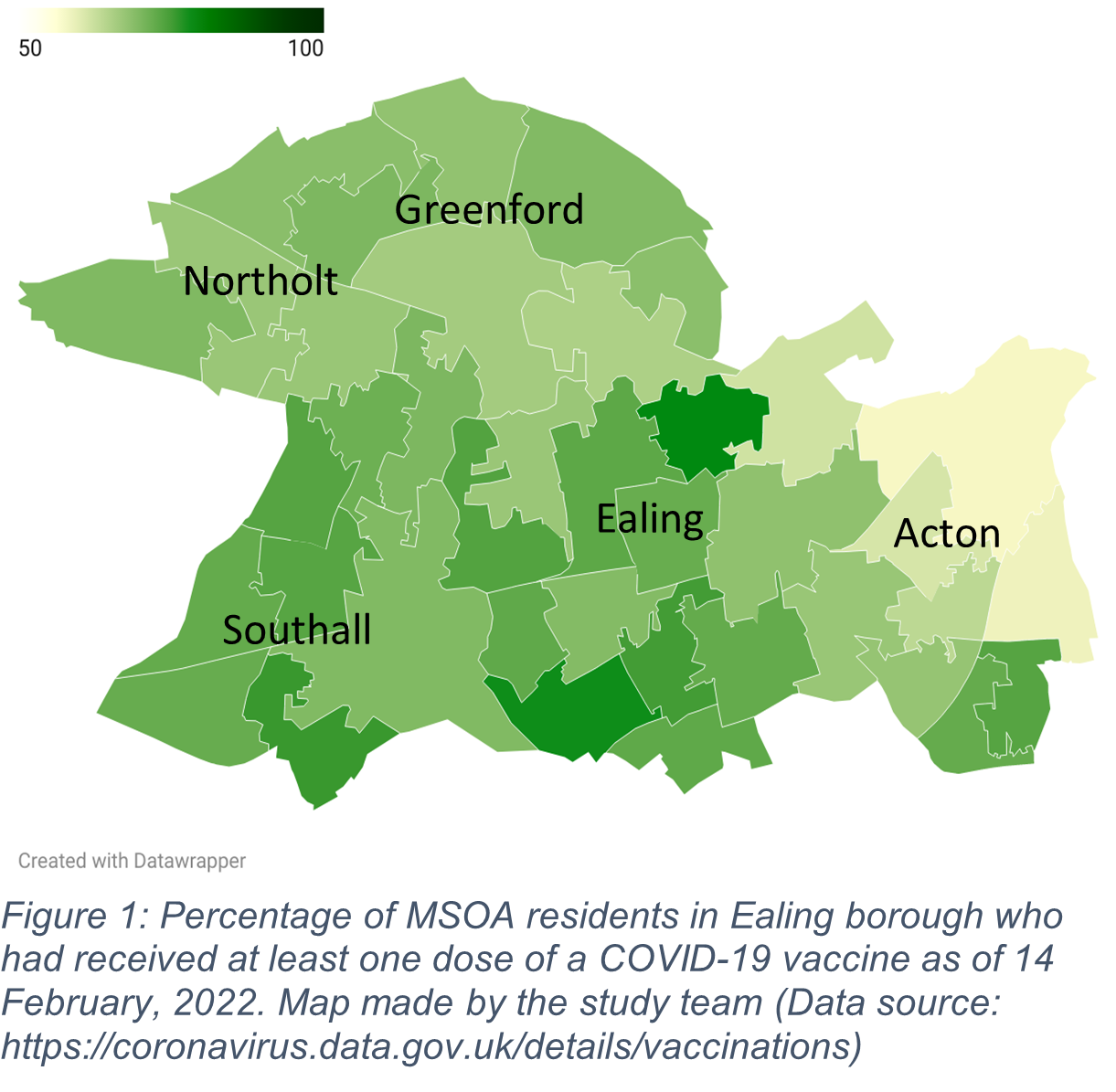

COVID-19 vaccination rates. In England, roughly 53.4% of 12-15 year olds had received one vaccine dose as of May 2022.5 Yet, national vaccination data have revealed major disparities by ethnicity. For instance, by mid-January 2022, 66% of Indian, 59% of White British, 27% of Black African, and just 12% of Black Caribbean 12-15 year olds attending state-funded schools had received a vaccine.6,7 For Ealing youth, 45.5% of those aged 12-15 and 54.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by mid-May 2022. More broadly, 69.3% of all residents over age 12 had received at least one dose while 64.5% had received two doses by this date.8 Local disparities are evident in data on vaccine uptake rates in different areas of the borough. As of mid-May 2022 for instance, areas in Acton, including South Acton (68.1%), Acton Central (64.3%), North Acton (59.1%) and East Acton (58.8%) all had lower than average first dose uptake among residents aged 12 and over (see Figure 1 for a map depicting first dose uptake by MSOA in February 2022).9COVID-19 vaccine roll-out. At the time of research, a key statutory authority responsible for vaccination rollout in Ealing was the Ealing NHS Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), itself part of the larger Northwest London Clinical Commissioning Group. The CCG has worked with the local Ealing Council to implement the rollout, including choosing venues, allocating human resources, and adapting the programme. Initially, the rollout began with two central sites selected by the CCG, including one in the town of Southall, which had been disproportionally affected by COVID-19 infections, serious illness, and death. Over time, due to advocacy by council-based responders, the rollout became more agile and responsive to residents’ needs, as illustrated, for instance, by the deployment of temporary pop-up clinics in various locations across the borough (i.e., faith centres, schools, supermarket parking, etc.).

Youth vaccine eligibility & permissions. Youth vaccination began in August 2021, when young people ages 16-17 became eligible to receive COVID-19 vaccines, followed by youth ages 12-15 in September. While adults can receive Moderna, Oxford/AstraZeneca, or Pfizer-BioNTech, only the Pfizer vaccine is available for those under 18. As of February 2022, only people aged 16 and up were eligible for a booster dose. Parental consent is sought for COVID-19 vaccination for youth under the age of 16.10,11 However, children can consent for themselves if they are deemed competent following an evaluation by a medical professional trained in the ‘Gillick competence’ framework.10 Despite the now widespread availability of vaccines to youth, COVID-19 itself was widely portrayed as a disease affecting the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions. This, alongside the fact that vaccines were not initially available for young people, created confusion about whether they are necessary or appropriate for them, which continues to require concerted effort to overcome.

YOUNG PEOPLE’S TRUST IN VACCINES

Trust, medical mistrust, and distrust during COVID-19. Trust12 affects the reception, interpretation, and spread of health communication on COVID-19 measures and vaccines. While loss of trust has been documented as a ‘key determinant’ of vaccine hesitancy, trust is often over-simplified. Different histories and experiences mean that trust in vaccines is both ‘highly variable and locally specific.’13

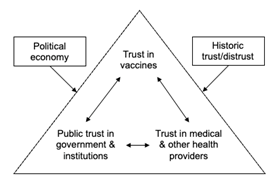

Understanding trust in COVID-19 vaccines requires a recognition of the complex factors that shape mistrust (Figure 2), for example amongst minoritised youth who may disproportionately face challenges related to inequality, racism, oppression, and injustice.

In this brief we link to different, interconnected aspects of trust, including public trust in government,2 trust in vaccination,13 and interpersonal and medical mistrust (see Box 1).14

Box 1: Trust in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

Trust can be defined as ‘a relationship that exists between individuals, as well as between individuals and a system, in which one party accepts a vulnerable position, assuming the … competence of the other, in exchange for a reduction in decision complexity,’13 such as providing information on the advantages and disadvantages of different decisions.12,13

Public trust in government refers to trust in all types of government institutions.15

Trust in vaccination includes trust in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, trust in pharmaceutical companies that develop vaccines, trust in the individuals that administer vaccines or give advice about vaccination, and trust in the wider health system.13

Medical mistrust means a tendency to distrust medical systems and personnel believed to represent the dominant culture in a given society.14 Medical mistrust often reflects longstanding historical injustice that has continued to today.

Public trust in government. Trust is a cornerstone of the relationship between communities and government and is the foundation for the legitimacy of public institutions.17 The OECD reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, trust in public institutions has been vital for governments’ abilities to respond rapidly to threats while maintaining citizen support.2 The OECD identified five main public drivers of trust in government institutions, including the latter’s ability to deliver services.18 However, as highlighted in this brief, trust cannot be oversimplified, but rather must be understood in a wider context. These five main drivers highlight the relationship between trust and the provision of quality public services to improve living conditions.

- Responsiveness. Provide and regulate public services.

- Reliability. Anticipate change, protect citizens.

- Integrity. Use power and public resources ethically.

- Openness. Listen, consult, engage, and explain to citizens.

- Fairness. Improve living conditions for all.

Systemic racism and trust. Research has indicated that experiences of injustice are widely viewed to affect public trust, medical mistrust and COVID-19 vaccine confidence.19,20 Medical mistrust and distrust in authorities often reflect experiences of racism and inequalities which can in turn influence responses to COVID-19 vaccines. Amongst adults from minoritised communities, medical mistrust is linked to broader negative experiences with authorities that have led to the breakdown of trust more generally.

FINDINGS ON TRUST & COVID-19 VACCINES

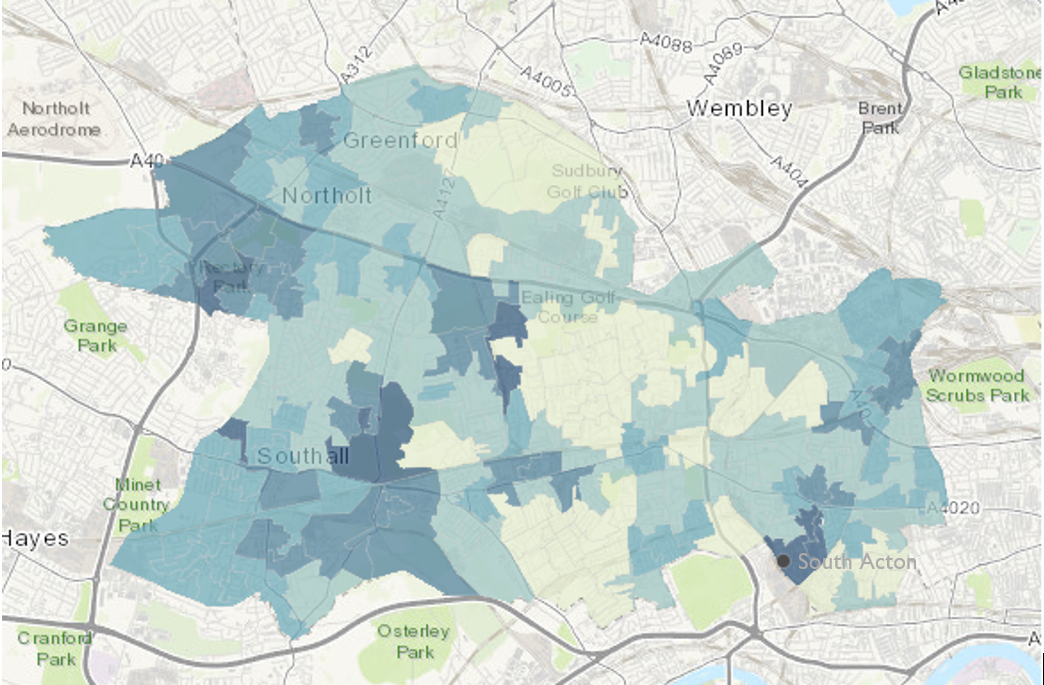

In January-March 2022, our team conducted traditional and participatory research using a Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) approach in Ealing. We collected data from over 62 young people (ages 12-19) – largely from minoritised backgrounds – from the borough. We focused on areas such as South Acton (higher deprivation) and Greenford (lower deprivation) (see Figure 3), with interviews also from other parts of Ealing. We found that youth attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination are embedded in political-economic and historical contexts, which includes experiences of racism, xenophobia, and economic exclusion in the UK. Minoritised youths’ distrust in the broader COVID-19 response, a lack of trust in political authorities, and/or distrust in broader institutions shape their responses to COVID-19 vaccines.21 The remainder of the brief explores the specific findings of our study, highlighting youth perceptions of trust/distrust and the context of COVID-19 vaccination.

Vaccination uptake among study participants

Out of 27 interview participants, 13 (48%) were not vaccinated, 11 (41%) were vaccinated with at least two doses, and 3 (11%) had received 1 dose. This varied greatly by location, as 71% (n = 10) of South Acton participants were unvaccinated compared to just 12% (n = 1) of Greenford participants. Two out of three of our focus group participants in Northolt were unvaccinated, while the one who was vaccinated said they had been forced to get vaccinated by their mother. For Acton focus group participants (n = 14), roughly half were also unvaccinated, whereas focus group participants in Southall (n = 15) were mostly vaccinated. This maps onto overall vaccination rates by area in Ealing, with Acton, including South Acton, having lower vaccination rates compared to other areas.

Connecting distrust to vaccine decision-making

While all young people in this study broadly lacked trust in government, some were vaccinated nonetheless, claiming to instead trust the scientists who promoted the safety of the vaccines. Those who were unvaccinated were more likely to mistrust the vaccines themselves, as well as the people and institutions involved in their development and promotion. This mistrust was rooted in several factors.

- Lack of investment in young people. In part, young people mistrust institutions due to a lack of investment in opportunities for them. In this study, young people who spent time in youth centres, described the value of these public services. Participants from Northolt – another particularly deprived area in Ealing – travelled over an hour each way to reach the youth centre in South Acton because there was no comparable option where they lived. However, youth centres are under-funded, and this disinvestment affects youth from deprived areas more acutely.

- Labels of deviance. Many young people in this study felt that society labelled them as ‘troublemakers,’ whether it was for allegedly flouting COVID-19 rules, or for everyday ‘anti-social’ activities. As reported by the Ealing youth worker and matched by study findings, young people are aware of this discourse, which contributes to their sense of social exclusion and marginalisation. Some young people feel ‘shut out’ of British society before they are even adults.22 Being frequently portrayed as ‘bad’ in social discourse is sometimes mirrored in vaccination discourse around youth who are non-compliant.23 It is important to avoid stigmatised labelling of the unvaccinated as non-compliant as it risks further alienating those who lack trust in institutions and systems.

‘I feel like the youth are quite isolated. I remember at one point, it was the youth that was blamed for spreading the virus with the parties and everything. And what I feel like no one thought about at that time, is what the actual youth thought or what we were doing. I feel like we should be considered a bit more.’

–Female, 16 years old, Greenford

- Distrust of government and local authorities. Government was not trusted across age groups, particularly in light of recent ‘partygate’ revelations about the lack of adherence to COVID-19 rules by senior government leadership. And while youth had low trust in politicians at the national level, they were less familiar with local politicians and had fewer opinions on local government. Medical trust and trust in government is embedded in young people’s relationships with other adults in their lives, particularly those in positions of authority. It is often impossible to separate ‘trust in government’ from trust in educational and police institutions, which shape the everyday lives of minoritised youth.

- Experiences of systemic racism and distrust. Experiences of living on estates or in deprived areas like South Acton or Northolt shape young people’s experiences in the education system and with police surveillance. Minoritised youth often experience the education system as racist and perceive the police to abuse their power by arbitrarily stopping and searching teenage boys. As the Ealing youth worker’s own data showed, these feelings of social exclusion can have ripple effects in terms of mistrust in government and authorities, and ultimately, vaccine hesitancy. However, while a large majority of youth did not trust public institutions, some of them did still accept COVID-19 vaccines.

‘They do this quite frequently, maybe two times a month. They’ll just turn up at my block, or estate, they’ll turn up and they’ll just walk up and down the stairs. They’ll be hiding out. Trying to catch anyone…they’ll get angry when they don’t get anybody doing anything or having any drugs or anything like that. A few times, they harass us….They stop me, search me, and they started insulting me, about where I live. It was so odd! They were really trying to get a reaction out of me. They said ‘are you embarrassed to be living here’? It’s so out of order. He’s got his camera rolling, he’s not ashamed. I told him, ‘what kind of question is that?’’

–Male, 18 years old, South Acton

- Structural inequalities, lived experience and prioritisation. Youth’s responses to COVID-19 vaccines also relate to experiences of deprivation. For youth in deprived areas, daily concerns are passed onto youth by their parents and peer groups, which may relate more to everyday experiences of racism or socioeconomic deprivation than COVID-19. Unvaccinated youth may not be as concerned about COVID-19, or may not perceive it as relevant to their lives, and cited this as one reason for not being vaccinated.

The Ealing sample was ethnically diverse, with intersections of race/ethnicity and class. These differences also mapped onto local geographies, with youth in the relatively more resourced area of Greenford expressing very different experiences compared to youth in the more deprived area of South Acton. This showed up in how young people in more deprived areas experienced the pandemic in relation to other ongoing challenges, and how this created a less conducive environment for taking up COVID-19 vaccines. In deprived areas, communities may prioritise livelihood security and safety over concerns about COVID-19.

- Uncertainty about COVID-19 vaccine safety. In terms of vaccine refusal, we heard stories of young people who did not trust the safety of the vaccines and who felt it was best to avoid getting them. We heard more stories related to uncertainty than to certainty about the vaccines. Many who are ‘vaccine hesitant’ are inundated with information, unlikely to know which information to trust, less likely to have a parent convincing them to get vaccinated or to be vaccinated, and less likely to have friends who are vaccinated. This creates an information and social ecosystem whereby young people are less exposed to positive vaccine information, stories and anecdotes.

‘You don’t know what will happen in five years if you take the vaccine, because the side effects aren’t there yet, but they will be later. I just don’t trust it. So why is the government forcing us to take the vaccine, can’t go anywhere without this vaccine, can’t do anything. And soon we’re gonna have these little cards that we need to travel and everything. Like, why is that necessary?’

–Female, 18 years old, South Acton

Understanding and engaging with trust

- Community distrust. Distrust by communities in government and public institutions shapes how minoritised youth with strong connections to migrant communities, black communities or other historically oppressed groups view the government and public institutions. These community experiences, alongside everyday lived experiences of inequality and racism, particularly for older youth, create an environment in which authorities (writ large) are less likely to be trusted.24 In these contexts, it becomes easier to question vaccine safety. Indeed, based on historical experience, it is prudent to be cautious when accepting new or potentially unsafe medical technologies.

- Youth understandings of trust. In this research, young people described what ‘trust’ meant to them. While it was difficult to define as an abstract concept, young people operationalised trust as being based on relationships they have with others. They could trust someone if they ‘knew them,’ knew their intentions, and how they were likely to behave toward others. Circles of trust for young people from more deprived areas were much smaller compared to youth from less deprived areas. They were wary of outsiders, particularly in the more deprived study areas of South Acton, Acton, and Northolt. In some cases, participants described trusting only close family members or friends. Young people in this study spoke about trust in various ways, most often as associated with:

-

-

- Privacy in interpersonal relationships and the notion that someone will not tell others what you have told them in confidence.

- Intentionality, or having good intentions and having an individual’s best interest at heart.

- Familiarity, or knowing someone for a while, which allows you to anticipate how they think and act toward others.

- Reputation, or how others view an individual’s character and trustworthiness.

- Reliability, or repeatedly doing something that is viewed as good.

-

‘I mean, to trust someone, you would have to know in some way, shape or form that they’re trustworthy. That kind of defeats the question, but they will have a reputation where you know that they’re not going to be untrustworthy. Because if they have a reputation of being untrustworthy, or lying, or being inaccurate, then you wouldn’t trust them.’

– Female, 16 years old, Greenford

- Trust and intuition. While some youth spoke about ‘distrust’ when speaking about COVID-19 vaccines, others displayed decision-making based on ‘gut feelings,’ or intuition. When young people come from communities that have experienced historical injustice, they may draw on those community experiences when evaluating government-provided information on vaccines.

- Engaging youth and building trust through youth centres. Young people in this study, particularly those who spent time in youth centres, described the value of these spaces to their lives. For participants in Action and South Acton, the local youth centre was a safe place they could go after school or work to meet friends and find support from youth centre workers. Several young men among our South Acton participants described the primary youth centre worker as a ‘father’ or second father figure who provided support, skills training, and life and career advice, as well as referred them to specialised social and health services when necessary. They felt they could speak to him openly, and that he listened to their perspectives, whereas they did not have this kind of support elsewhere. Unvaccinated youth were more reliant on youth centres, making them positive spaces with lots of potential for rebuilding trust with marginalised youth.

- Supporting young people’s needs to improve living conditions for all. Building trust with young people is relevant not only for the management of COVID-19, but for building further legitimacy for other government-led efforts in the future. Young people identified several challenges that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic and that continue today, including challenges with mental health, educational support and support from teachers, livelihood security within the home, and having safe spaces to go after school to avoid recruitment into local gangs or other criminality. Respondents from a recent survey by a local youth worker asked for the following support from local government:

Young people’s messages for policy makers

- Financial, food, and economic support

- More job and career opportunities

- Safety and reduced crime in their neighbourhoods

- More youth friendly activities, like indoor football

- More youth clubs and youth centres, including spaces for homework and study

- Better access to trained mental health practitioners

- Opportunities to meet with authority figures and decision-makers

- Improved relationships of trust with local government

CONCLUSION

It is vital that we understand youth distrust of vaccines as embedded in context and rooted in the histories of their communities. In Ealing, austerity policies have led to funding cuts for council services. This includes youth services, which provide critical opportunities upon which at-risk youth in particular, fundamentally rely. In places like South Acton, gentrification has displaced young people who increasingly feel they are being pushed to the margins of society without help or support to thrive. In the absence of opportunity, young people living in poverty must think about working, avoiding the police, and getting through a school system that they perceive values them less. The experiences of young, minoritised, socio-economically deprived participants fundamentally shape how they relate to and respond to public health guidance on COVID-19 vaccines.

REFERENCES

-

-

- Hrynick, T., & Ripoll, S. (2021). Evidence Review: Achieving COVID-19 Vaccine Equity in Ealing and North West London. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform. https://www.socialscienceinaction.org/resources/evidence-review-achieving-covid-19-vaccine-equity-in-ealing-and-north-west-london/

- OECD. (2022). Enhancing public trust in COVID-19 vaccination: The role of governments. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/enhancing-public-trust-in-covid-19-vaccination-the-role-of-governments-eae0ec5a/

- Greater London Authority. (2020). London’s children and young people who are not British citizens: A profile. Greater London Authority.

- Ealing Council. (2020). Equalities Needs Assessment (UK). Ealing 1.12 WISP Migration. https://www.ealing.gov.uk/downloads/download/2043/equalities_needs_assessment

- Download data | Coronavirus in the UK. (n.d.). Retrieved 20 May 2022, from https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/download

- Adams, R. (2022). Disparities in children’s Covid vaccination rates map England’s social divides. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/feb/01/disparities-in-childrens-covid-vaccination-rates-map-englands-social-divides

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination uptake in school pupils, England—Office for National Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved 20 May 2022, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/articles/coronaviruscovid19vaccinationuptakeinschoolpupilsengland/upto9january2022

- UK Government. (n.d.). Vaccinations in Ealing. Coronavirus in the UK. Retrieved 20 May 2022, from https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/vaccinations?areaType=ltla&areaName=Ealing

- UK Government. (n.d.). Interactive map of vaccinations | Coronavirus in the UK. Retrieved 20 May 2022, from https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/interactive-map/vaccinations

- Daly, A., Stalford, H., & Barry, K. (2021). COVID vaccines for under-16s: Why competent children in the UK can legally decide for themselves. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/covid-vaccines-for-under-16s-why-competent-children-in-the-uk-can-legally-decide-for-themselves-168047

- Gov.uk. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination programme for children and young people: Guidance for schools (version 3). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-resources-for-schools/covid-19-vaccination-programme-for-children-and-young-people-guidance-for-schools

- Verger, P., & Dubé, E. (2020). Restoring confidence in vaccines in the COVID-19 era. Expert Review of Vaccines, 19(11), 991–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2020.1825945

- Larson, H. J., Clarke, R. M., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Levine, Z., Schulz, W. S., & Paterson, P. (2018). Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(7), 1599–1609. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252

- Benkert, R., Cuevas, A., Thompson, H. S., Dove-Meadows, E., & Knuckles, D. (2019). Ubiquitous Yet Unclear: A Systematic Review of Medical Mistrust. Behavioral Medicine (Washington, D.C.), 45(2), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2019.1588220

- OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust | en | OECD. (n.d.). Retrieved 4 April 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/governance/oecd-guidelines-on-measuring-trust-9789264278219-en.htm

- Gamble, V. N. (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health, 87(11), 1773–1778.

- The Royal Society. (2020). COVID-19 vaccine deployment: Behaviour, ethics, misinformation and policy strategies (p. 35).

- Trust in Government—OECD. (n.d.). Retrieved 4 April 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm

- Larson, H. J., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Smith, D. M. D., & Paterson, P. (2014). Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine, 32(19), 2150–2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081

- Enria, L., Bangura, J. S., Kanu, H. M., Kalokoh, J. A., Timbo, A. D., Kamara, M., Fofanah, M., Kamara, A. N., Kamara, A. I., Kamara, M. M., Suma, I. S., Kamara, O. M., Kamara, A. M., Kamara, A. O., Kamara, A. B., Kamara, E., Lees, S., Marchant, M., & Murray, M. (2021). Bringing the social into vaccination research: Community-led ethnography and trust-building in immunization programs in Sierra Leone. PLOS ONE, 16(10), e0258252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258252

- Davies, B., Lalot, F., Peitz, L., Heering, M. S., Ozkececi, H., Babaian, J., Davies Hayon, K., Broadwood, J., & Abrams, D. (2021). Changes in political trust in Britain during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: Integrated public opinion evidence and implications. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00850-6

- Booth, R., & correspondent, R. B. S. affairs. (2018, November 14). Shut out of society, young Londoners talk to UN poverty envoy. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/nov/14/shut-out-society-young-londoners-un-poverty-envoy-philip-alston

- Hrynick, T., Schmidt-Sane, M., & Ripoll, S. (2020). Rapid Review: Vaccine Hesitancy and Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccination.

- Hosking, G. (2019). The Decline of Trust in Government. In M. Sasaki (Ed.), Trust in Contemporary Society (Vol. 42). Brill.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This brief was produced by SSHAP in collaboration with partners in Ealing. It was authored by Megan Schmidt-Sane (IDS), Jillian Schulte (Case Western Reserve University), Tabitha Hrynick (IDS), Charlie Forgacz-Cooper (Youth Advisory Board), and Santiago Ripoll (IDS), with contributions from Steve Curtis (Ealing Council), Helen Castledine (Ealing Public Health), Hena Gooroochurn (Ealing Council), and Janpal Basran (Southall Community Alliance), and reviews by Elizabeth Storer (LSE) and Annie Wilkinson (IDS). The research was funded through the British Academy COVID-19 Recovery: USA and UK fund (CRUSA210022). Research was based at the Institute of Development Studies.

CONTACT

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Olivia Tulloch ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and Wellcome Grant Number 219169/Z/19/Z. This briefing is from a project funded by the British Academy under the COVID-19 Recovery: Building Future Pandemic Preparedness and Understanding Citizen Engagement in the USA and UK Programme. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of IDS, Anthrologica or LSHTM.

KEEP IN TOUCH

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Schmidt-Sane, M., Schulte, J., Hrynick, T., Forgacz-Cooper, C. and Ripoll, S. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccines and (Dis)Trust among Minoritised Youth in Ealing, London, United Kingdom. Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) DOI: 10.19088/SSHAP.2022.010

Published May 2022

© Institute of Development Studies 2022

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode