This brief summarises key considerations concerning cross-border dynamics between Tanzania and Uganda in the context of the outbreak of Ebola (Sudan Virus Disease, SVD) in Uganda. It is part of a series focusing on at-risk border areas between Uganda and four high priority neighbouring countries: Rwanda; Tanzania; Kenya and South Sudan. The current outbreak is of the Sudan strain of Ebola (SVD). SVD is used in this paper to refer to the current outbreak in East Africa, whereas outbreaks of Zaire Ebolavirus disease or general references to Ebola are referred to as EVD.

The current outbreak began in Mubende, Uganda, on 19 September 2022, approximately 240km from the Uganda-Tanzania border. It has since spread to nine Ugandan districts, including two in the Kampala metropolitan area. Kampala is a transport hub, with a population over 3.6 million. While the global risk from SVD remains low according to the World Health Organization, its presence in the Ugandan capital has significantly heightened the risk to regional neighbours. At the time of writing, there had been no cases of Ebola imported from Uganda into Tanzania.

This brief provides details about cross-border relations, the political and economic dynamics likely to influence these, and specific areas and actors most at risk. It is based on a rapid review of existing published and grey literature, previous ethnographic research in Tanzania, and informal discussions with colleagues from the Tanzania’s Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC), Tanzania National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), Uganda Red Cross Society, Tanzania Red Cross Society (TRCS), International Organization for Migration (IOM), IFRC, US CDC and CDC Tanzania. The brief was developed by Shelley Lees and Mark Marchant (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine) with support from Olivia Tulloch (Anthrologica) and Hugh Lamarque (University of Edinburgh). Additional review and inputs were provided by The Tanzania Red Cross and UNICEF. The brief is the responsibility of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP).

Geographical Context

Border Region and Physical Terrain

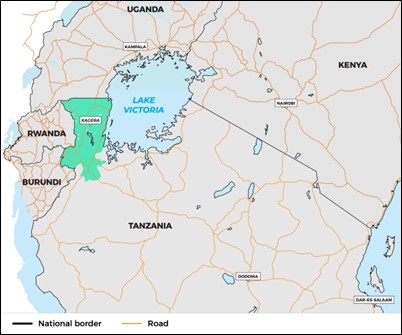

The land border between Uganda and Tanzania stretches 150km from a mountainous tripoint between Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania in the west to the shores of Lake Victoria in the east. On the western end, approximately one-third of the land border’s length lies on the Kagera River, which also forms the border between Tanzania and Rwanda. From the shoreline of Lake Victoria, the border crosses the lake for 240km along the first parallel south to a tripoint border with Kenya and Uganda on the eastern side.

- Border regions: Two regions of Uganda make contact with the Tanzanian border: Western Region and Central Region. On the Tanzania side, the districts of Kyerwa and Misenyi (Kagera Region) both contact the border (Map 1). The regional capital and largest city in Kagera is Bukoba, approximately 80km from the Ugandan border by road.

- Human geography: Most of the borderland is sparsely populated, with small towns and villages on the Uganda side between Kikagati and Bugango and between Mutukula and the shoreline of Lake Victoria. Although the western tripoint area is more densely populated than most of the rest of the Uganda-Tanzania border, the Kagera river forms a natural barrier and there are few crossing points.

- Islands: Several islands near the lake border area have mixed populations of Kenyans, Ugandans and Tanzanians. In all areas of the lake, these islands are for the most part inhabited by fishermen and highly mobile populations. Other island inhabitants tend to be involved in cross-border trade around Lake Victoria, some of whom live more permanently on the islands. Ukerewe is the largest of the lake islands and sits 45km (28m) north of Mwanza and linked by a ferry. On the western side of the lake, Nyangoma Island lies on the Ugandan side of the border and is reached by both Ugandans and Tanzanians by boat.

| Map 1. Kagera region and surrounding borders |

|

Source: Authors’ own.

Historically Contested National Boundaries

The border between Tanzania and Uganda has a long history of contestation, and community notions of insider-outsider relations will be important for RCCE, surveillance, and contact tracing.

- Border dispute: Regions north of the Kagera were annexed in 1978 by Uganda’s Idi Amin in the run up to the country’s failed invasion of Tanzania. After Uganda lost the war and Amin was exiled, the border dispute continued, with more Ugandan settlers moving onto the Kagera Salient. The removal of border markers by parties involved in the conflict resulted in a 25-year period of relative ambiguity about where exactly the border line fell, until a joint technical committee set up by both countries reaffirmed the current border in 2003.

- Refugees and settlers: During the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, thousands of Rwandans fled across the border into Tanzania where many remain today, mostly in the Kagera Region. After nearly 30 years, many of those who remain are fluent Swahili speakers and are well integrated into Tanzania. However, national tensions persist around Tanzania’s expulsion of Ugandans from the Kagera Region. More recent settler groups, including Rwandan immigrants, may not be as welcomed.

- Expulsions: In 2013, the Tanzanian government expelled thousands of migrants from the DRC, Rwanda and Uganda, who had settled in the Kagera region due to its high annual rainfall and strong agricultural capacity. During this ‘Operation Kimbunga’, some of those who were expelled claimed to be Tanzanians who had been misidentified as Ugandan settlers.

- Discrimination: Some Ugandans see the Ugandan settlers on the Tanzania side as being routinely victimised.1 These attitudes could affect views of insider-outsider group relations in the event of an SVD outbreak, especially if it was seen to be brought by Ugandans into Tanzania. Several thousand of the Ugandans who were expelled were relocated to Sango Bay in Uganda’s Kyotera District, and others to Nakivaale. There were reports of a plan for a compensation scheme for those settlers who were relocated after building households, farms and lives on the Tanzania side, but the settlers have claimed in the media that this never materialised.1

Border Crossings and Migration

Formal land Crossing Points

The main official crossing point is at Mutukula, where a One Stop Border Post (OSBP) was established in 2017. This crossing is part of the East African Community’s (EAC) Central Corridor, a regional effort to improve trade efficiency. On average, over 400 vehicles cross the border at Mutukula daily. The other main crossing point on the Tanzania-Uganda border is Murongo (Kikagati on the Uganda side) in Kyerwa District. Murongo has more direct transport connections to Kigoma and onward travel to Burundi than the Mutukula border crossing. Murongo does not have an OSPB.

Large sections of the border remain unmarked, and many people cross without passing through formal immigration facilities. This is especially true in Bugango. Many people living on both sides of the border maintain family, kinship and business relationships across the border, especially in Bugango and Mutukula, which straddle the border.

Buses, other passenger vehicles and freight trucks entering Tanzania at the OSBP in Mutukula travel to various parts of Tanzania, including Bukoba, where many passengers transfer to Mwanza, Geita and Kigoma, or travel directly to Dar es Salaam. The Minister of Health announced in October 2022 that between five and 10 buses travel directly from Kampala to Dar es Salaam daily via Mutukula; other reports from our consultations said the average was about 14 per day.

Despite its long distance from Kampala (over 1600km), Dar es Salaam is considered high risk due to the high-quality transport infrastructure and trade and transport links to the border areas and the possibility that people with SVD symptoms from other regions may travel to the major city to seek medical care. The bus route is so long that passenger and cargo vehicles can pass through Kenya instead, with passengers changing buses in Nairobi. Travelers making the Kampala-Dar es Salaam journey through Kenya would most commonly enter Tanzania through Namanga.

Preparedness at Points of Entry

Preparedness work for EVD was undertaken during the 2018-2020 outbreak in the DRC, with IOM and CDC supporting Tanzania’s Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) on public health emergency response plans for points of entry. This included quantitative and geospatial work supported by IOM on population movements and qualitative and systems strengthening work supported by CDC on information-sharing and cross-border collaboration. A contingency plan for EVD outlines “mitigation and preparedness actions for addressing coordination, epidemiological surveillance and Point of Entry surveillance, case management, laboratory services, risk communication, social mobilization and community engagement, Psychosocial as well as logistics services.”

Points of entry were identified as a priority area of intervention and the responsible institutions are the MoH, President’s Office – Regional and Local Government (PORALG), IOM, WHO, UNHCR and CDC. Currently, these partners work through the National Task Force and regional and district health offices, led by RMOs and DMOs. Management committees at each POE are composed of emergency response team members, and at land border crossings, these include staff from both sides of the border. Standard operating procedures (SOPs), trainings and job aids have been created and delivered at points of entry for multi-sectoral staff (customs, immigration, airlines, police).

| Map 2. Tanzania major road connections and official crossings |

|

Source: Authors’ own.

Multiple partners involved reported that these contingency plans are solidly in place at POEs. IOM has provided equipment, supplies like temperature scanners and personal protective equipment (PPE) to border agency staff. At the time of writing, the Mutukula OSBP was reported to have temperature checks, video screens playing information about how SVD spreads, and newly installed sinks for handwashing. Travellers entering Tanzania were being asked about their recent contacts, whether they had attended a funeral, had symptoms (fever, headache, body aches), and their telephone numbers and vehicle license plate numbers were being documented for follow-up.

Communication and sensitisation work has taken place around the primary border crossing points at Mutukula and Murongo in Tanzania. Community health workers (CHWs) and Tanzania Red Cross Society (TRCS) volunteers are also posted at the main border crossings and some porous border areas for health promotion and sensitisation work. Standing committees at border crossing points bring together staff from both sides to manage cross-border issues, including disease surveillance and ongoing health promotion on both the Ugandan and Tanzanian sides.

Informal Land Crossings

The border is highly porous, with dozens of towns and villages set close to it. Bugango, in Uganda’s Isingira District and Tanzania’s Misenyi District, straddles the border and has been a focal point of the border dispute, with individuals and families relocated out of the Tanzania side. This area is more porous and not as heavily monitored as official points of entry at Mutukula and Murongo.

Instead of multi-sectoral interventions through border control systems, porous border areas like Bugango have health promotion and surveillance through community health workers (CHWs), Regional and District health systems, and international partners including IOM and TRCS. There are ongoing efforts to train CHWs specifically on identification and reporting of SVD to improve community surveillance capacity in the porous border areas.

Lake Victoria Crossing Points

Lake borders create unique difficulties in terms of disease control, due to a combination of highly mobile populations (generally fishing communities), unregulated cross-border movement, access difficulties to outlying islands, and the prevalence of economic activities – notably smuggling – that encourage populations to avoid state authorities. In the case of Tanzania, the following considerations are relevant:

- Lakefront regions: Four of the five regions identified by the Government of Tanzania as high-risk for Ebola transmission from Uganda have borders on Lake Victoria (Kagera, Geita, Mwanza, Mara), and can be reached by boat from Uganda.2 The regions around Lake Victoria are some of the most densely populated in Tanzania.

- Simiyu: One region with a small border on Lake Victoria (Simiyu) was not identified as a region of high-risk. The Lake Victoria shores of Simiyu are remote given the shape of the coastline, making Mara and Mwanza regions with longer coastlines and more port cities on either side closer to reach than Simiyu.

- Lake districts in Kagera: In Kagera Region, the lake-bordering districts are Bukoba Urban, Bukoba Rural, Muleba and Biharamulo. Nyangoma Island in Uganda is just north of the border with Tanzania, offshore from the mouth of the Kagera River and the Kagera Triangle, and fishing and trade vessels use this island as a hub. Nyangoma can be reached by boat from Uganda or Tanzania and often has a mixed population.

- Ferries: Several large passenger ferries, shipping barges and fishing boats travel from the main port cities: Entebbe and Jinja in Uganda; Bukoba and Mwanza in Tanzania, and Kisumu in Kenya. However, there are currently no large passenger ferries on Lake Victoria between Uganda and Tanzania. Transport barges with only a crew (and no or few passengers) and smaller fishing boats and canoes (ngalawa) cross the lake border between Uganda and Tanzania at over 100 entry points with high interaction between the two countries, according to multiple partners consulted on the issue. Fishermen commonly seek out prime fishing locations and markets for sale based on the location of fish populations and the best market prices.

- Islands and HIV: Historically, there has been high prevalence of HIV on the islands in Lake Victoria, which was among the early routes of transmission along trucking routes around the lake and fishing routes (island and port cities) on the lake. Engagement and risk communication work in these areas may need to acknowledge the existing higher prevalence of HIV and perceptions of local communities of isolation or neglect from mainland Tanzanians and government in these areas compared to other parts of Tanzania.

- Island surveillance: On the shoreline of Lake Victoria, community surveillance will remain important as a high volume of lake crossings from Uganda into Tanzania do not pass through formal immigration. In Kagera Region, like on the islands in Lake Victoria, a sense of distance, isolation and possibly neglect by national government could impinge on views of preparedness and outbreak response work. Engagement with local official and unofficial leaders will be valuable for ensuring preparedness work is fully implemented. Consideration should be for deploying social scientists to train community health workers on observations and informal conversations to better understand border movements. Training and data collection can be conducted rapidly.

Socio-Political Context in Tanzania

Political Context

Tanzania’s dominant party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), has held the presidency and a majority in the Tanzanian National Assembly for 60 years, and political opposition to it remains weak.

Freedom Watch reported that, since the election of President John Magufuli in 2015, the government “cracked down with growing severity on its critics in the political opposition, the press, and civil society”.3 When Magufuli died in March 2021, then-Vice President Samia Suluhu Hassan became the country’s first female president. The current administration has suspended certain publications and arrested Freeman Mbowe, the chairman of the opposition party Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (Chadema) on charges of terrorism after he gave a speech on constitutional reform. The presidential power to appoint regional and district commissioners across the country extends power of the ruling party to all levels of government.

There is often hesitation among government officials to provide information, even if it is not confidential or controversial, without the authority from the appropriate ministry or department. It will be important for preparedness and response partners to work closely with government structures to facilitate the flow of information, access to communities and the support of local leaders based on the approval of more senior officials.

Formal letters granting approval for certain activities can sometimes be substituted by a phone call or other direct communication in the event of emergencies. Often this process can be facilitated by MoHCDGEC with regard to emergency decisions, through PO-RALG to address chain of command issues, and through District and Regional officials when decisions are specific to their jurisdictions.

Freedom of Press and Information

Tanzania has several major daily newspapers, television and radio news outlets and a growing online and social media environment. Outputs are tightly controlled by central government authorities.

- In 2022, Freedom House described the media environment in Tanzania as “subject to harsh repression”.3 The 2016 Media Services Act gave the national government broad authority, often along CCM party lines, to control content and license outlets. Penalties for violating it include prison terms for publishing defamatory or seditious content. Broad interpretation by the ruling party on what constitutes such acts results in media and academic self-censorship.

- President Suluhu Hassan, who took office in 2021, has lifted bans on some media outlets but her administration suspended other publications.

- The 2015 Statistics Act prohibits the publication of information that conflicts with that from the Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (TNBS). This has limited some publications’ ability to criticise the government openly, and this could affect information sharing in an infectious disease response. For example, it prevented publication of COVID-19 case numbers during the pandemic in Tanzania from May 2020 until mid-2021. Publication of cases resumed after President Hassan took office.

Ethnic Identities and language

Tanzania has over 120 ethnic groups, though virtually all Tanzanians speak Swahili. Tanzania’s first president, Julius Nyerere, promoted national unity among over 120 ethnic groups through an education system conducted in Swahili from primary school onwards. This has resulted in a high degree of linguistic uniformity across Tanzania and makes Swahili the primary language of disease response and sensitisation.

The Sukuma ethnic group is the largest in Tanzania and surrounds much of the southern shores of Lake Victoria, including Mwanza. The largest ethnic groups in Kagera Region are the Haya and Nyombo. No ethnic group has a simple majority, so coalition politics across ethnic groups is a must to win majority elections, and in general Tanzanians proudly identify as Tanzanian first before identifying with tribe or ethnicity.

Burial Practices

Burial practices vary across Tanzania’s religious and ethnic groups, and the regions identified as high-risk for SVD transmission are highly culturally diverse. Some common practices in funerals and mourning traditions may present risk of disease transmission:

- Funeral ceremonies: Funerals are for the most part expected to be communal, with planning committees for different activities, like catering, grave-digging and burial, fundraising and organising ceremony speeches, and grieving publicly both by attending a funeral and wearing mourning clothing among other practices, is important to show solidarity.

- Access: Preparedness teams would need to consider a broad set of stakeholders (elders, religious leaders, local government officials, party chairs, traditional healers) to engage on adaptations of burial practices that present risk of transmission.

- Historical precedent: Burial practices that present risk of disease transmission have been modified in the past around HIV/AIDS in consultation with communities and in the context of EVD in other contexts.4

- Clothing and fabrics: In Kagera Region near the Ugandan border, Haya people, among others, use clothing and fabrics as a “critical medium for articulating descent,” including white cloth used to wrap the body of the deceased.5 In the Haya language, to say someone is “wearing bark cloth” means they are in mourning, even though traditional bark cloths used in burials have largely been replaced by white cloth. Often, capes or gowns worn by mourners are cut from the same cloth that wraps the deceased for burial. The cloths are traditionally purchased by the spouses of the deceased person’s children and this process is of such importance that Haya people casually ask, “If I don’t have children, who will bring funeral shrouds?”.5 Among the Sukuma and many other groups in Tanzania, relatives and community members washing the body of the deceased is common but not universal.

Healthcare System and Ebola Response

Health Status and Healthcare System

- Demography and health: Tanzania has a population of 53.5 million with 45% under 14 years and 68% living rurally. Life expectancy is 71 years for women and 68 years for men and maternal mortality is 399/100,000.6

- Public/private healthcare: Most health care provision is public (74%) with the majority of private (14%) and faith-based (13%) provision based in Dar es Salaam and Arusha.7

- Healthcare tiers: The health system has three levels, primary, secondary and tertiary. At the primary level, hospitals are referral centres for all primary health facilities that include public and private dispensaries and health centres.

- Hospitals: The Regional referral hospital and other referral hospitals at the secondary level are referral centres for all primary level facilities. Zonal referral hospitals are tertiary level referral centres for secondary level facilities. Specialized hospitals are national referral centres for specialized services.8 National hospitals, zonal referral hospitals, regional referral hospitals and district hospitals total 263 of which 13% are private and 40% are faith based. Primary health care centres, clinics and dispensaries total 7178.

- Performance: The performance of the health system is mixed, achieving targets for HIV/AIDS, malaria, TB and child health but not for reproductive health.9 Over 67% of the population lives within 5km of a health facility, although there is unequal distribution of health facilities.

- Health workers: Tanzania suffers from a health worker shortage with over 500 dispensaries without skilled health workers.9 There are 0.9 doctors per 10,000 population, 4.9 nurses per 10,000 population, and 0.12 pharmacists per 10,000 population.

- Traditional Medicine: More than 60% of Tanzanians depend on traditional medicines to treat diseases, and both the Haya and Sukuma ethnic groups (concentrated around Lake Victoria in the at-risk regions) are known for their expertise in, and use of, traditional medicines. Even among those practicing Islam or Christianity, traditional beliefs remain. Belief in spirits and curses means that many people seek out traditional healers for herbal medicines and other treatments or ‘witch doctors’ to address an illness understood to be a curse. The Government of Tanzania has announced engagement activities in September 2022 with traditional healers in the high-risk regions, but it is unclear how extensive or successful these have been.

Epidemic Preparedness and Response

- Guidelines: In 2001, Tanzania adopted the International Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) framework.10 In 2011, the guidelines were revised to incorporate the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) as well as non-communicable diseases. It currently includes 34 priority diseases divided into four major groups: 1) Epidemic prone diseases; 2) Diseases targeted for elimination/eradication; 3) Diseases of public health importance, and 4) Others. Epidemic-prone diseases include cholera, bacillary dysentery, plague, measles, yellow fever, cerebrospinal meningitis, rabies, animal bite, smallpox, anthrax, viral haemorrhagic fevers (Rift Valley fever, Ebola, Marburg, dengue, Lassa fever etc), human influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory infection and keratoconjuctivitis.11

- Reporting: An evaluation of the disease reporting performance in June 2018 found that the average timeliness and completeness was 63% and 75%, respectively, and only for two months did the average completeness reach the national target of ≥80%. There were concerns at the time of the review that this would affect the timely detection of diseases and rapid response and there was a need to improve timeliness and completeness by upgrading the system used for data collection so as to allow immediate data capture, analysis and response to prevent outbreaks.11

- Ebola experience: Tanzania has not experienced an Ebola epidemic. However, in 2019 there was a suspected case of a Tanzanian doctor who died on 8th September after returning to her country from Uganda with Ebola-like symptoms. Several contacts of the woman became sick, and the Tanzanian authorities reported that they had tested negative for Ebola. These tests were not shared for validation under the International Health Regulations, a treaty designed to protect the world from spread of infectious diseases.12 The WHO issued a statement urging the country to provide patient samples for testing at an outside laboratory. There were also suspected cases of Ebola in July 2022 in Lindi, Tanzania. However, following testing it was found to be an outbreak of Leptospirosis with a reported total of 20 cases and three deaths.12

- HIV/AIDS: The North Western areas of Tanzania have a high incidence of HIV/AIDS relative to other parts of the country.13 Bukoba, a town near the Ugandan border, was among the early epi-centres of the HIV/AIDS outbreak and spread across East Africa. The use of traditional medicine in treating HIV/AIDS is well documented, but less frequent the sole treatment of choice with the expansion of access to antiretroviral treatment, especially in Tanzania’s Lake Victoria regions.

- Cholera: Tanzania is particularly prone to cholera outbreaks with the longest recorded outbreak between August 2015 and December 2018 with a recorded total 33,319 cases and 550 deaths (CFR 1.7%). A recent Cholera outbreak was recorded in Katavi, Rukwa and Kigoma in the first half of 2022 with a total recorded 435 cases and 8 deaths (CFR 1.8%).14

- COVID-19: As of 9 December 2022, there had been 40,806 cases and 845 deaths reported, and as of the latest report on 27 November 2022, over 32.8 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered.15 The National Task Force led by the Prime Minister was activated to coordinate the National COVID-19 Response. Additionally, an inter-ministerial committee, headed by the Chief Secretary and the Technical Task Force led by the Permanent Secretary, were formulated to provide technical guidance to contain COVID-19 epidemic in the country.17

Ebola Preparedness and Response

Previous Assessment of Ebola Epidemic Preparedness

In 2019, the MoHCDGEC assessed readiness for Ebola in Tanzania. Using the WHO Checklist, the existence of coordination, trained Rapid Response Teams (RRT), infection prevention and control (IPC), public awareness and community engagement, case management including safe dignified burial, epidemiological surveillance, and contact tracing was assessed in eight regions with a high risk including those that border DRC (Kigoma, Kagera, Mwanza, Songwe, Rukwa, Mbeya, Katavi and Dar es Salaam).

- The assessment found that gaps existed in rapid response systems, epidemiological surveillance, contact tracing, and safe and dignified burial.

- The assessment found that a total of 438 health care workers (HCWs) had been trained; 190 on rapid response teams, 106 on case management, and over 142 on event-based surveillance and contact tracing. Over 122 community health workers had been trained on event-based surveillance and contact tracing.

- Risk communication guidelines had been developed and distributed to all priority regions.

- Medical equipment and supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE), standard case definitions (SCD), factsheets, and laboratory standard operations procedures (SOPs) on Ebola sample collection, storage, and transportation were distributed to priority regions.

- Public awareness creation and sensitisation campaigns were implemented through media, social networks, and Ebola National Walks campaigns. Moreover, targeted trainings were done for the media, musicians, and community groups.

The assessment concluded that the likelihood of having an EVD outbreak was high, and that Tanzania was operationally prepared to respond to and prevent an EVD outbreak in the country.17 It noted that the capacity to detect, respond and contain Ebola is limited despite the roll out of the IDSR guidelines discussed above.

At the time of the report, Event Based Surveillance coverage was only 30% across the country. The national and regional rapid response team’s capacity was moderate because the last training was completed four years prior to the report. Capacity is also limited because Tanzania has not experienced an EVD outbreak and IPC practices are limited amongst frontline health care workers. On a positive note, strategies put in place for RCCE for COVID-19 are adaptable for Ebola.

A readiness assessment from simulation exercises in 2019 in Kagera and Kigoma found that gaps exist in all pillars (coordination, surveillance and POE, laboratory, case management and IPC/WASH, risk communication and community engagement including psychosocial support). From August 2018 to September 2019, 30 alerts have been reported in Tanzania a country with a population of about 50 million. Alert reporting may be lower than expected due to the low capacity of HCWs. Around 300 HCWs at Regional, District and health facility levels had been trained in respective thematic areas on Ebola preparedness and response. Coordination across the relevant sectors is lacking or inadequate.

Current Situation

As of September 2022, Tanzania has constructed four standard Ebola Isolation centres in Temeke and Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Mawenzi in Kilimanjaro and Buswelu in Mwanza. Each has a capacity of 16 beds, with minimal equipment and staff for proper handling of a case.17

The MoHCDGEC leads the response in accordance with the Tanzania Disaster Management Act (2015).16 The Prime Minister’s Office will support coordination in case of event escalation and attends multi-sectoral National Task Force (NTF) meetings. The Disaster Management Department (DMD) is responsible for coordinating the higher-level meetings on quarterly basis and when there is an escalation it will convene the Tanzania Disaster Management Council (TADMAC).17

A suspected or probable case of EVD constitutes a public health emergency, and this event will trigger a Level II response. A confirmed case of Ebola will trigger activation to Level III. In cases of EVD outbreak, the Regional and District Public Health Emergency Operations Centres (PHEOC), the National PHEOC, and the Emergency Communication and Operation Centre (EOCC) will facilitate coordination of response as outlined in the All Hazard Emergency Response Plan and Public Health Emergency Concept of Operation.17

The Incident Management lead is responsible for the overall response operation and will work with the PHEOC manager and the various pillars (including Case Management and IPC, Laboratory, Surveillance, Vaccines, Research, Risk Communication and Community Engagement, Continuity of Essential Health Services, Research and Points of Entry.

On 28 September 2022, the Ministry of Health made a statement about the risk of SVD spreading to Tanzania due to cross border trading. High risk areas were identified as Kagera, Mwanza, Kigoma, Geita and Mara. High risk areas identified due to air travel and bus routes were identified as Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Kilimanjaro, Songwe, Mbeya and Dodoma. The National Task Force on Public health was called to prepare for a potential outbreak. Each region under the Public Health Act 2009 is expected to develop a contingency plan, and to strengthen surveillance and reporting of Ebola cases through the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system.17 The statement emphasised the following actions:

- Rapid Response Teams were ordered to conduct training activities.

- Screening for Ebola was introduced at the Uganda-Mutukula border, in Dar es Salaam, Kilimanjaro, Kigoma and Mara.

- Strengthening the Rapid Response Team and strengthening health centres in each District council in Kagera. This includes the availability of blood, medical equipment and supplies, and PPE in all health centres.

- Strengthening the transportation of samples to the national laboratory in Dar es Salaam.

- Improvements in testing and laboratory capacity in the Kagera region.

- Strengthening of surveillance of travellers from Uganda.

- Strengthening of contact testing.

- The specification of areas for burials.

- Ensuring the availability of water and soap for hand washing.

- Strengthening communication activities with the general public.2,18

The MoHCDGEC published a contingency plan for Ebola in September 2022.14 It conducted an assessment using a WHO checklist and found that SVD importation likely has a high risk of community spread in Tanzania.

Due to the increased risk of SVD in Kigoma, Kagera and Mbeya, Katavi and Songwe, planning for constructing standard isolation facilities is in place. There is now a revised contingency plan to support case management at the 46-official points of entries. By September 2022, 23 borders had begun screening, and had capacity to hold a suspected Ebola case temporarily before transporting them to an ETC.

There are four Biosafety level (BSL3) laboratories capable of testing Ebola in Dar Es Salaam, Mbeya, and Kilimanjaro Regions, with adequate supplies. There is formalised specimen transportation (EMS) from sample collection facilities to these testing laboratories.17 Tanzania, at time of writing this brief, was awaiting a PPE shipment.

According to the MoHCDGEC, in September 2022 there were 20-25 HCWs trained in Ebola preparedness and response per region which they assessed as insufficient to cover the number of health facilities in the region and districts.17

A readiness assessment conducted by WHO on 8 November 2022 found that the SVD Readiness Status for Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Tanzania varied by response pillar.19 With 69% for IPC but only 52% for point on entry. Overall, Tanzania was assessed as moderately ready, with an overall score of around 70%. WHO reported that the 1st National Task Force was conducted on 7th November. There have been 11 alerts which were all negative. WHO also reported that Tanzania had 48 isolation beds and USD 1.7 million in funds.19

There is also limited capacity to address rumours and misinformation and training on RCCE had not commenced at time of writing this brief.

Acknowledgements

This brief has been written by Shelley Lees and Mark Marchant (LSHTM). We would like to acknowledge the expert contributions made by colleagues from Tanzania’s Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MOHCDGEC), Tanzania National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), Uganda Red Cross Society, Tanzania Red Cross Society (TRCS), International Organization for Migration (IOM), IFRC, US CDC and CDC Tanzania. It was reviewed by Olivia Tulloch (Anthrologica) Hugh Lamarque (University of Edinburgh), The Tanzania Red Cross and UNICEF. The brief is the responsibility of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP).

Contact

If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, would like to request a briefing on a particular theme, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Olivia Tulloch ([email protected]).

The Social Science in Humanitarian Action is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica, Gulu University, ISP Bukavu, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

KEEP IN TOUCH

Twitter: @SSHAP_Action

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter

Suggested citation: Lees, S. and Marchant, M. (2022) Key Considerations: Cross-Border Dynamics between Uganda and Tanzania in the Context of the Outbreak of Ebola, 2022. Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) DOI: 10.19088/SSHAP.2022.046

Published December 2022

© Institute of Development Studies 2022

This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.

References

- Musisi F. Aliens in their own country | Monitor [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/special-reports/aliens-in-their-own-country-3803036

- Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. Notice to the public about the threat of the Ebola disease outbreak [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.moh.go.tz/storage/app/uploads/public/633/463/a1d/633463a1d036a781344772.pdf

- Freedom House. Tanzania: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report [Internet]. Freedom House. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://freedomhouse.org/country/tanzania/freedom-world/2022

- Saguti E. Alternative Rituals of Widow Cleansing in Relation to Women’s Sexual Rights in Zambia. Submitted in Fulfilment of the Academic Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, College of Humanities, University of Kwazulu-Natal. 2016.

- Weiss B. Dressing at Death: Haya Adornment and Temporality. In: Hendrickson H, editor. Clothing and Difference: Embodied Identities in Colonial and Post-Colonial Africa [Internet]. 1996. p. 133–54. Available from: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters/32

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC in Tanzania [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/countries/tanzania/default.htm

- Pharm Access. The healthcare system in Tanzania [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.pharmaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/The-healthcare-system-in-Tanzania.pdf

- Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. All-hazard public health emergency response plan [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://drmims.sadc.int/sites/default/files/document/2020-03/All%20hazard%20%20ERP%282%29_0.pdf

- West-Slevin K, Barker C, Hickmann M. Snapshot: Tanzania’s health system [Internet]. Health Policy Project, Futures Group; 2015 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/803_TanzaniaHealthsystembriefFINAL.pdf

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response in the African Region: Third edition [Internet]. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/technical-guidelines-integrated-disease-surveillance-and-response-african-region-third

- Kishimba R, Mghamba J, Mohamed M, Subi L. Is Tanzania prepared to respond and prevent Ebola outbreak? Tanzan Public Health Bull. 2019;1(1):14.

- Branswell H. WHO signals alarm over possible unreported Ebola cases in Tanzania [Internet]. STAT. 2019 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.statnews.com/2019/09/21/who-signals-alarm-over-possible-unreported-ebola-cases-in-tanzania/

- Kissling E, Allison EH, Seeley JA, Russell S, Bachmann M, Musgrave SD, et al. Fisherfolk are among groups most at risk of HIV: cross-country analysis of prevalence and numbers infected. AIDS Lond Engl. 2005 Nov 18;19(17):1939–46.

- Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. Contingency Plan for Ebola Viral Disease Preparedness and Response [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://crisisresponse.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1481/files/appeal/documents/EVD%20C%20Plan%20_%20FInal%20Op.pdf

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. United Republic of Tanzania: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int

- Government of the United Republic of Tanzania. Disaster Management Act (No. 17 of 2015) [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.climate-laws.org/geographies/tanzania/laws/disaster-management-act-no-17-of-2015

- Ministry of Health. 2022. Contingency Plan for Ebola Virus Disease. 2022.

- CGTN. Tanzania issues alert over Ebola after new outbreak reported in Uganda [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 9]. Available from: https://newsaf.cgtn.com/news/2022-09-22/Tanzania-issues-alert-over-Ebola-after-new-outbreak-reported-in-Uganda-1dwa9PShwWY/index.html

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. WHO Operational Readiness in Priority 1 and 2 countries SVD in Uganda. 2022.