Since 2009, the Boko Haram insurgency has become the most prominent source of violence in northern Nigeria, particularly affecting the north-east. The group’s activities, including bombings, assassinations, and mass abductions, have resulted in over two million people being displaced and a severe humanitarian crisis.1,2 Clashes between farmers and herders over land and resources in central Nigeria have spread to northern states, intensifying the existing humanitarian crisis.2 In addition, north-west Nigeria regularly experiences banditry that is characterised by kidnappings for ransom, armed robbery and village raids. The prevalence of violence has destabilised the northern region with severe physical, emotional, social and psychological consequences.

Trauma is the lasting emotional response that often results from living through a distressing event. This emotional response may harm an individual’s feeling of safety, sense of self and ability to regulate their emotions and navigate relationships. These changes may result in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3,4 In Nigeria, individuals who have experienced psychological trauma and who can be said to be experiencing PTSD from a biomedical perspective remain largely untreated.

In 2014, the conflict in northern Nigeria received global attention with the ‘Bring Back Our Girls’ campaign in response to the mass kidnapping of 276 female students in Chibok.5 The military action and the establishment of camps for displaced persons that came with this global attention increased Nigeria’s reliance on aid from humanitarian agencies.5 Despite the expansion of humanitarian services in the northern conflict zones since 2014, access to conflict-affected populations remains challenging due to the increasing and expanding security crisis. Humanitarian operations are hindered by inadequate service delivery as a result of the lack of strong and concerted advocacy for coordinated efforts across international diplomatic and humanitarian actors.

This brief examines trauma in northern Nigeria, comparing the biomedical framing of PTSD with the social science understanding of the drivers of and possible solutions for mental health impacts of trauma. The brief also describes the management of humanitarian service operations in the northern conflict zones.

The brief draws on the SSHAP workshop ‘Health and Humanitarian Issues in the Conflict Context in Northern Nigeria’ (held in April 2024), consultation with humanitarian service delivery experts and humanitarian researchers active in or knowledgeable about the region and its conflict, and academic and grey literature.

Key considerations

- Promote role distribution and coordinated humanitarian service operations. To avoid wasting resources through duplication of service delivery, governments should map out humanitarian needs and share these responsibilities among service providers.

- Prioritise addressing trauma and its metal health impacts as a major component of humanitarian service delivery. Beyond aid provision, humanitarian services should prioritise trauma and post-trauma management as a core need of affected people. This will improve the quality of life for individuals who have experienced violence as a result of armed conflict.

- Create awareness among vulnerable populations about impacts of trauma as well as the clinical and social support services available to them. Awareness of available trauma and post-trauma management services in humanitarian operations will lead to increased uptake of these services and reduce the burden of this mental health need among vulnerable populations.

- Coordinate and partner with local community-based institutions for design and delivery of more acceptable and effective trauma and post-trauma humanitarian service delivery. Experience has shown that for effective delivery of humanitarian services, implementers should engage individuals, institutions and networks that are already based and active within affected communities for the design, implementation and evaluation of service delivery.

- Provide social science training for service providers so they can generate data to identify early warning signs for conflicts and associated trauma, and promote conflict resolution and community stabilisation strategies to reduce the incidence and prevalence of trauma and post-trauma stress disorders. To improve the support services for individuals with trauma and PTSD, both humanitarian service providers and health workers should be trained on relevant social science methods for a better understanding of their environment and collaborative problem-solving.

Social and political context of the conflict zones of northern Nigeria

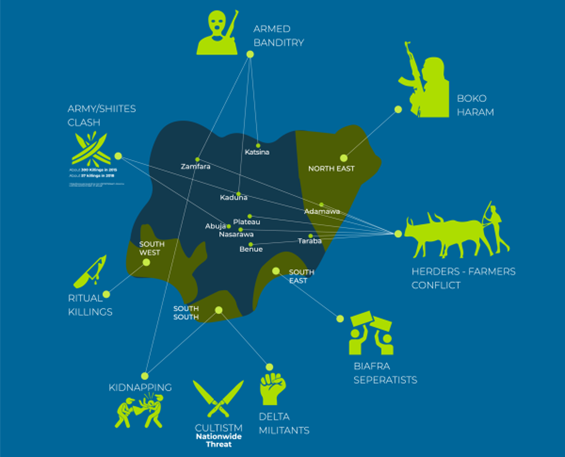

As depicted in Figure 1, over the last decade, northern Nigeria (composed of the north-west, north-east and north-central geopolitical zones) has experienced severe crises that have affected individuals and the operation of institutions.6 These crises have been triggered mainly by Boko Haram terrorists and local armed groups6 and have caused internal displacement and severe hardship. The crises have negatively impacted the economies of the affected areas through loss of livelihoods and increased poverty.6 As of 2024, it has been estimated that 8.8 million people, including more than 5 million children, are affected by the crises.7

State, international and local partners have responded to the situation with humanitarian aid and services to help enhance the resilience of affected communities.8 The country’s federal government, through the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, is responsible for coordinating the response in line with the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ Humanitarian Response Plan.8

The response plan requires international and local actors’ interventions to be sustainable and linked to the long-term development of the affected communities.8 Interventions and programmes from international organisations are expected to be localised through a participatory approach that includes involving state actors, relevant non-governmental agencies and community members in planning and implemention.9 The Humanitarian Response Plan has guided most humanitarian programming in the north-eastern part of Nigeria that is most affected by terrorism issues.

Figure 1: Location of violent conflicts in Nigeria

Source: Idayat Hassan, from From Boko to Biafra: How insecurity will affect Nigeria’s elections.10 This figure is licensed under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Share Alike 4.0 International License.

Note: The above map is from 2018. The conflicts shown are still active and have, in some cases, further escalated.

It has been observed by scholars that even though the north-east and north-west have experienced the same magnitude of humanitarian crises and therefore require comparable humanitarian help, over the last decade the north-eastern part of the country has received more humanitarian services from both local and international actors.11 This unequal response persists even though it is clear the north-west has a critical need for humanitarian help.11 For instance, a 2023 survey found that in north-western Nigeria 64% of all local governments had reported severe cases of acute malnutrition while the figure was 22% in the north-east.12

The unequal prioritisation experienced between these two regions has been attributed to humanitarian aid providers’ perceptions of the crises.11 Political and media stakeholders in Nigeria attribute the situation in the north-east to terrorism while describing the situation in the north-west as lawlessness or endemic banditry by local armed groups.11 This description simplifies the situation in the north-west and means that less attention is directed to that part of the country by local and international humanitarian service providers. Linking the crises in the north-east to Islamic extremism has enabled the region to receive attention from humanitarian actors because terrorism-related issues gain more attention globally.11,13–15

Different perspectives of post-trauma disorders

Trauma, derived from the Greek word for ‘wound’ or ’hurt’, is a subjective experience perceived as painful or distressing and results in acute or chronic mental and physical impairment or dysfunction.16,17 Trauma has traditionally been understood through a biomedical, i.e., clinical and psychiatric, lens, focusing primarily on individual symptoms, diagnoses and neurobiological responses. However, the social science perspective offers a broader and more complex understanding of trauma, framing it as an inherently social and collective experience that extends beyond the individual to impact entire communities, cultures and social structures.18,19 This perspective emphasises the role of societal and cultural factors in both the experience of trauma and its long-term effects, including the development of PTSD.

Globally, trauma and its mental health impacts are significant public health concerns, with about 3.9% of the global population affected by PTSD.4 In conflict zones, the prevalence of PTSD and related disorders is higher, with one in five individuals affected.20 Previous studies on trauma and PTSD in Sierra Leone, Algeria, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Gaza and former Yugoslavia highlight the high prevalence of long-term mental health disorders, including PTSD, in conflict zones underscoring the need for targeted mental health interventions.20,21–22,23

Social science perspective

The social science approach views trauma as not merely an individual psychological response but as a phenomenon shaped by social structures, cultural norms and collective histories. Traumatic experiences are often deeply intertwined with social inequalities, discrimination and violence, making the social context a critical determinant of how trauma is experienced and processed.

Cultural trauma is a form of collective memory that links traumatic events, such as slavery or genocide, to the identity of a group.24 Cultural trauma is transmitted through generations and manifests in collective practices, narratives and mental health issues that persist over time.24,25

Trauma is socially constructed, meaning that the interpretation of trauma is shaped by how society and communities define what constitutes a traumatic event. Social trauma occurs when large groups of people are affected by a catastrophic event, such as war, displacement or systemic oppression. These events can create a shared sense of loss and disruption that extends beyond the psychological experience of individuals to the broader social fabric.26,27

Social science explains PTSD in the context of interaction. For instance, it has been reported that individuals who develop PTSD due to a lack of social support and empathy from social networks are more likely to be fearful of negative interactions, such as in conflicts, compared to those who do not develop PTSD as a result of exposure to traumatic experience.28

In contrast to the somewhat narrower centralisation of mental health in the biomedical perspective, the social support theory emphasises the protective role of social networks in mitigating trauma effects.29 This theory focuses on behaviour, cognition and the protective role of social support.

The social science perspective on trauma and post-trauma disorders expands the understanding of trauma beyond the individual to encompass the collective, cultural and structural dimensions of traumatic experiences. By emphasising the role of social support, community resilience and collective healing, this approach offers a more comprehensive view of trauma that is critical for developing effective interventions and fostering long-term recovery.

Biomedical perspective

Within biomedical literature, psychological trauma refers to emotional and mental distress resulting from traumatic events that manifests as anger. Psychological trauma resulting from conflicts includes PTSD, depression and stress, all of which profoundly affect individuals’ well-being and functionality.20 According to this understanding, PTSD is a specific type of trauma disorder triggered by traumatic events, characterised by symptoms such as intrusive memories, avoidance, negative changes in thinking and mood, and changes in physical and emotional reactions.30

Several psychological theories explain trauma and PTSD within the biomedical literature. Classical and operant conditioning theories elucidate how trauma triggers and avoidance behaviours develop.31 Cognitive and cognitive processing theories focus on maladaptive thought patterns and processing disruptions.32 Dual representation and biological theories highlight trauma memory types and neurobiological responses.33

Other trauma-related disorders in the biomedical framing include acute stress disorder, complex PTSD and adjustment disorders, each with specific symptoms and impacts. Acute stress disorder involves severe anxiety and dissociative symptoms shortly after trauma, while complex PTSD is understood to come from prolonged trauma exposure and leads to difficulties in emotional regulation and interpersonal relationships. Adjustment disorders occur in response to significant life changes or stressors and cause emotional and behavioural symptoms.34,35

It is important to recognise that the conceptualisation of PTSD as a clinical diagnostic category cannot characterise the different experiences and impacts of trauma. This characterisation requires the use of other approaches, such as cross-cultural tools, that can examine locally-relevant idioms of distress and explanatory models of illness and account for ongoing stress and adversity.36

Combined approaches

Integrating the social science perspective with clinical approaches can allow for the development of a more holistic model of trauma recovery that goes beyond trauma on the individual and allows health providers to contextualise how trauma is experienced by and manifests among different individuals and social groups. By recognising the limitations of a disease-based understanding of trauma and purely medicalised treatments (such as cognitive behaviour therapy and medication), humanitarian agencies can deploy a wider range of socially appropriate intervention strategies. Combining clinic-based approaches with community-based interventions that address the social determinants of health, may therefore lead to more effective long-term outcomes for trauma survivors.37

Post-trauma disorders in conflict-affected communities in northern Nigeria

Understanding the incidence and prevalence of mental health impacts – specifically trauma and post-trauma disorders – of banditry and terrorism and the resultant violence and displacement in northern Nigeria is crucial for addressing the mental health needs of affected communities and developing effective interventions.

Specific data on northern Nigeria is limited due to several challenges, including a lack of comprehensive studies, cultural stigma leading to underreporting, displacement, inaccessibility and resource constraints in mental health infrastructure.38,39 However, based upon a small number of studies, there are indications that even with a narrow clinical definition of PTSD, significant numbers of people in the northern conflict zones might be experiencing mental health impacts of trauma.

A clinical study among internally displaced youth exposed to Boko Haram terrorism found around two thirds met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.40 Another study in the Yobe state found that more than 90% of displaced people exhibited signs of PTSD and depression.41 While this research provides valuable insights about the likely burden of mental health needs among trauma exposed communities, it needs to be supplemented with research that can examine the nature of different traumatic experiences and identify the different ways in which distress might be expressed across different cultural and individual contexts.

The loss of loved ones, especially husbands and breadwinners, poses a serious challenge for women and children in the conflict zones. Most women and children witnessed the killing of their husbands and fathers. Most survivors of violence in the northern conflict zones are dependents or have lost their means of livelihood through being displaced.

Recent reporting has highlighted that security officials also need mental health support services and that this group is often forgotten in assessments and interventions. The Peoples Gazette of 13 June 2024 reported the Nigerian Chief of Army Staff, Lt. General Taoreed Lagbaja sharing that his fighters in the north-east and north-west were struggling with battle fatigue, trauma and PTSD. Other research has revealed that retired soldiers from the battlefront also have had encounters with trauma and PTSD.42

In Nigeria, socio-cultural factors significantly influence mental health. Stigma and cultural perceptions often stop individuals from seeking help for mental health issues43 and traditional beliefs and religious practices shape the understanding and management of mental health.44,45 For instance, the Kanuri people see PTSD as ‘unwanted thoughts, anxieties, and worries’ that represent fate and are an act of God. The Kanuri people believe PTSD can be overcome through religious and spiritual interventions.46 The Yoruba ethnic group of south-western Nigeria define trauma as aiwo. Aiwo is considered to be the source of all other illnesses and is associated with restlessness and psychological imbalance. For the Yorba, aiwo requires a spiritual solution because it is caused by afise, meaning it is an ‘affliction of the enemy’.47

The situation is compounded by the lack of adequate mental health infrastructure. For instance, Nigeria has less than 300 psychiatrists and similar number of nurses per 200 million people, against the standard practice of one psychiatric doctor per 10,000 patients. The lack of human resources for mental health continues to worsen with the exodus of health professionals out of the country due to the prevailing economic hardship and poor work conditions in the health sector.48

Addressing the mental health impacts of conflict in northern Nigeria is essential for improving individual well-being, enhancing public health outcomes and supporting effective humanitarian responses. Understanding trauma and PTSD, recognising the socio-cultural context and addressing data gaps are critical steps in developing targeted mental health interventions and policies. By integrating mental health services into emergency response and recovery programmes, policymakers and humanitarian organisations can better support affected communities and promote long-term healing and stability. Improving the mental health infrastructure and addressing policy gaps are crucial for enhancing mental health care in the region.49 Although gender dynamics, economic stress and poverty further exacerbate mental health problems, community and social support can provide emotional and practical help.50,51

The interplay between trauma and post-trauma disorders and society

The effects of trauma and post-trauma disorders on society cannot be overemphasised. Indeed, trauma and post-trauma disorders have profound adverse effects on values that promote cooperation and collaboration between individuals and groups in society. In northern Nigeria, for instance, the cooperation and collaboration that bridging social capital facilitates among people of diverse spiritual, cultural and political groups have mostly evaporated, leaving widespread, deep-seated resentment. The values that connect people and promote social cohesion barely exist in many of the conflict-affected communities in northern Nigeria.52,53

The social environment plays an important role in determining both the immediate and long-term effects of trauma. Traumatic responses are not merely biological or psychological phenomena but are deeply influenced by factors such as social support, community resilience and collective identity.54 For instance, research shows that social isolation, marginalisation and discrimination can exacerbate the psychological impact of trauma, leading to more severe and chronic post-traumatic disorders.55 Appraisals of social trauma, such as severe rejection, humiliation or exclusion, can play a critical role in determining whether PTSD or related disorders develop at the individual level. 56,57

PTSD can be exacerbated by societal responses to trauma, such as stigmatisation, discrimination or lack of access to mental health services. Communities that fail to provide adequate social support or resources for trauma recovery may contribute to the chronicity of PTSD, especially among vulnerable populations, such as refugees, survivors of abuse or people living in conflict-affected areas.58 Social policies and interventions that promote social cohesion, inclusivity and community-based mental health care have been shown to significantly redress the mental health impacts of trauma in humanitarian contexts.26

In cases of collective trauma, such as from natural disasters, political violence or forced migration, responses are often shaped by how well communities are able to mobilise social support systems. A community’s ability to organise, provide mutual aid and establish collective coping mechanisms can significantly mitigate the impact of trauma and prevent the development of chronic PTSD, even when the disorder is defined in medical terms. 26 Conversely, when individuals lack social support or are ostracised by their communities, their risk of developing long-term mental health issues, including PTSD, increases significantly.58

Cultural trauma arises when entire groups of people experience profound disruptions to their collective identity due to sustained violence or oppression. Communities in northern Nigeria are experiencing this form of trauma. Cultural trauma leaves lasting scars on the collective consciousness, often resulting in ongoing mental health disparities within the affected groups. Cultural trauma is a key driver of health disparities, as marginalised communities frequently suffer higher rates of PTSD and related mental health disorders due to the intergenerational transmission of trauma. 59

Collective healing is a core concept in the social science view of trauma. Recovery is not only an individual journey but a collective process that requires addressing the social and cultural legacies of trauma. This can include public acknowledgment of historical wrongs, communal rituals of mourning and reparative justice efforts, all of which help rebuild the social fabric torn apart by traumatic events. 24,25

Trauma responses and management in northern Nigeria

Conflict-affected communities in northern Nigeria and internally displaced persons (IDPs) are exposed to trauma and experience a high burden of mental health challenges as a result. There is a pressing need for the government and humanitarian agencies to address these mental health impacts.

Trauma and its impacts are mediated through cultural and social factors. This means that just as the exposure to conflict and trauma related distress varies among individuals, the ways in which individuals respond to distress and express its impacts also varies. This variation is not always captured in clinical diagnoses of PTSD.

Equally significantly, the way individuals and social groups respond to trauma is determined through a combination of individual as well as social and cultural factors. In northern Nigeria, the lack of awareness of mental health conditions and need for specialist interventions might act as a barrier to addressing the mental health needs of conflict-affected people. However, the cultural belief systems present might help communities make sense of their mental health challenges and the mobilised community-based social support systems are beneficial in the absence of state interventions.

Access to trauma management services has been poor and the mental health impacts of trauma are given limited attention and resources within state and non-governmental humanitarian interventions. An important reason for the poor access is likely to be the lack of information about where and why these services can and should be accessed.60,61

Government responses

The official government body that responds to complex humanitarian emergencies in Nigeria is the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA). NEMA establishes mission stations at trouble spots around the country and is guided by the National Action Plan for Disaster Risk Reduction, which is currently undergoing review. All states must also establish a State Emergency Management Agency.

NEMA is involved in trauma management as the kind of complex emergencies it responds to usually have traumatic effects on people. However, the agency’s resources are usually so limited that it cannot engage in interventions beyond counselling, referral to health centres and organising funded social activities.

The government’s provision of trauma management services is limited due to a lack of funds. In addition, uptake of the services offered is further restricted by the perception of corruption of state officials and the fact that services are mostly concentrated in urban areas.

Victims of trauma and people with PTSD, and those close to them, often complain of not getting the right support services from NEMA and or their state’s emergency management agency.

Humanitarian agency responses

Several international humanitarian organisations complement NEMA’s and state emergency management agencies’ efforts in managing trauma and PTSD in northern Nigeria. These are shown in Table 1 below.

However, these organisations do not concentrate exclusively on trauma-related problems. Observations suggest that many of these organisations adopt one-size-fits-all approaches to mental health services, which can mean those with trauma-related problems do not receive the level of attention they need. These agencies focus their trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder interventions in IDP camps in the north-east and north-west and in the capital city Abuja.

Table 1. Humanitarian organisations in northern Nigeria and their responses

| Organisation | Services related to trauma and PTSD |

| International Committee of the Red Cross | Provides psychological support and mental health services to victims of violence and conflict. |

| United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | Offers psycho-social support and counselling to refugees and IDPs. |

| Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) | Provides medical and psychological care to victims of conflict and violence. |

| International Rescue Committee (IRC) | Offers psycho-social support, counselling, and trauma care to IDPs and refugees. |

| Save the Children | Provides psychological support and counselling to children affected by conflict. |

| UNICEF | Offers psycho-social support and counselling to children and families affected by conflict. |

| World Health Organization (WHO) | Provides mental health services and support to conflict-affected populations. |

Source: Authors’ own.

To address the challenges in the northern conflict zones, it is important for humanitarian agencies to address the social roots of traumatic experiences and the different ways in which these might be expressed. Trauma management is important in the context of humanitarian services because trauma affects vulnerable populations and destabilises socioeconomic conditions.

Challenges and recommendations

The limited nature of mental health support currently available to victims of conflict means that it is important for state agencies to coordinate and partner with local and international humanitarian organisations engaged in providing trauma management services.

The role sharing among humanitarian service providers is not clear, leading to duplication of some services as well as the neglect of others, including trauma management. It is also not clear where trauma and PTSD services are available from the humanitarian service providers.

Studies have demonstrated the uniqueness of trauma care in conflicts. Lessons learned from physical healthcare in conflict settings can be used to improve the quality of services, reduce barriers and improve health outcomes for trauma care in the northern conflict zones.62,63

It is important to integrate social science insights in the design and provision of trauma services in conflict affected regions in Nigeria, including in the north and north-east. This will help humanitarian agencies provide context appropriate interventions. As discussed earlier, social science research has shown how different people try to make sense of mental health symptoms through their own cultural references. There needs to be more research among conflict-exposed communities from northern Nigeria to better understand their perceptions of distress and healing as well as to identify the community-based networks of support that are already active in these settings. This understanding will allow the design of interventions that align with local understandings of mental health, which are likely to find greater acceptance than purely Western, biomedically oriented therapies. Partnerships with existing community groups in the design and implementation of these interventions are also likely to make them more acceptable and effective.

References

- USIP. (2024). The Current Situation in Nigeria. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/04/current-situation-nigeria

- Crisis Group. (2024). Nigeria. Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria

- WHO. (2024). Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/post-traumatic-stress-disorder

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., De Girolamo, G., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000708

- Stoddard, A., Harvey, P., Czwarno, M., & Breckenridge, M.J. (2020). Humanitarian Access SCORE Report: Northeast Nigeria. Humanitarian Outcomes, USAID. https://humanitarianoutcomes.org/SCORE_report_NE_Nigeria_2020

- Hassan, I. (2018, December 18). From Boko to Biafra: How insecurity will affect Nigeria’s elections | African Arguments. African Arguments. https://africanarguments.org/2018/12/boko-biafra-nigeria-insecurity-2019-elections/

- OCHA. (2023). Humanitarian Response Plan Nigeria (Humanitarian Programme Cycle).

- ACAPS. (2024). Conflict in northeastern and north-western Nigeria (ACAPS Briefing Note). https://www.acaps.org/fileadmin/Data_Product/Main_media/20240103_ACAPS_briefing_note_conflict_in_northeastern_and_north-western_Nigeria.pdf

- OCHA. (2020). Humanitarian Response Plan Nigeria (Humanitarian Programme Cycle).

- CARE International. (2020). Integrated GBV prevention and response to the emergency needs of newly displaced women, men, girls, and boys in Borno State, North-East Nigeria: Baseline Report. https://www.careevaluations.org/wp-content/uploads/Integrated-GBV-prevention-and-response-to-the-emergency-needs-of-newly-displaced-women-men-girls-and-boys-in-Borno-State-North-East-Nigeria-Baseline.pdf

- Bryant, J., Ibrahim, A. A., & Obono, E. (2024). Aid beyond politics and according to need: Overcoming disparities in humanitarian responses in Nigeria (HPG Working Paper). ODI. www.odi.org/en/publications/aid-beyond-politics-and-according-to-needovercoming-disparities-in-humanitarian-responses-in-nigeria

- IPC. (2023). Nigeria (Northeast and North-west): Acute Malnutrition Situation for May—September 2023 and Projections for October—December 2023 and January—April 2024. IPC – Integrated Food Security Phase Classification. https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1156630/?iso3=NGA

- Azumah, J. (2015). Boko Haram in Retrospect. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, 26(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2014.967930

- Usman, Z., Taraboulsi-McCarthy, S. E., & Hawaja, K. G. (2020). Gender norms & female participation in radicalization. In A. R. Mustapha, K. Meagher, A. R. Mustapha, K. Meagher, A. K. Monguno, M. S. Umar, I. Umara, A. Idrissa, J. G. Sanda, D. Ehrhardt, S. El Taraboulsi, K. G. Hawaja, Z. Usman, M. Last, & I. H. Hassan (Eds.), Overcoming Boko Haram: Faith, Society & Islamic Radicalization in Northern Nigeria (pp. 193–224). Boydell and Brewer. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781787446595-013

- Ikpe, E., Adegoke, D., Olonisakin, F., & Aina, F. (2023). Understanding Vulnerability to Violent Extremism: Evidence from Borno State, Northeastern Nigeria. African Security, 16(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2023.2185746

- Kleber, R. J. (2019). Trauma and Public Mental Health: A Focused Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00451

- Friedberg, A., & Malefakis, D. (2022). Resilience, Trauma, and Coping. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 50(2), 382–409. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2022.50.2.382

- Alexander, J., Eyerman, Ron, R., Giesen, B., Smelser, N. J., & Sztompka, P. (2004). Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (1st ed.). University of California Press; JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pp9nb

- Hirschberger, G. (2018). Collective Trauma and the Social Construction of Meaning. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01441

- Eyerman, R. (2004). Cultural Trauma: Slavery and the Formation of African American Identity. In Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (pp. 60–111). University of California Press. https://academic.oup.com/california-scholarship-online/book/20485/chapter-abstract/179669158

- Volkan, V. D. (2021). Chosen Traumas and Their Impact on Current Political/Societal Conflicts. In A. Hamburger, C. Hancheva, & V. D. Volkan (Eds.), Social Trauma – An Interdisciplinary Textbook (pp. 17–24). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47817-9_2

- Hamburger, A., Hancheva, C., & Volkan, V. D. (Eds.). (2021). Social Trauma – An Interdisciplinary Textbook. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47817-9

- Dibo, S. (2022). The Sociocultural Trauma of Forced Migration and Displacement. Sotsiologicheskoe Obozrenie / Russian Sociological Review, 21(4), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.17323/1728-192x-2022-4-120-135

- Charlson, F., Ommeren, M. van, Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H., & Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 394(10194), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Charuvastra, A., & Cloitre, M. (2008). Social Bonds and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 (Volume 59, 2008), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650

- Bryant, R. A. (2011). Acute stress disorder as a predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09r05072blu

- Strain, J. J., & Friedman, M. J. (2011). Considering adjustment disorders as stress response syndromes for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(9), 818–823. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20782

- Patel, A. R., & Hall, B. J. (2021). Beyond the DSM-5 Diagnoses: A Cross-Cultural Approach to Assessing Trauma Reactions. Focus: Journal of Life Long Learning in Psychiatry, 19(2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20200049

- Tol, W. A., Barbui, C., Galappatti, A., Silove, D., Betancourt, T. S., Souza, R., Golaz, A., & van Ommeren, M. (2011). Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: Linking practice and research. Lancet (London, England), 378(9802), 1581–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61094-5

- Betancourt, T. S., McBain, R., Newnham, E. A., & Brennan, R. T. (2013). Trajectories of internalizing problems in war-affected Sierra Leonean youth: Examining conflict and post-conflict factors. Child Development, 84(2), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01861.x

- Ehlers, A., Maercker, A., & Boos, A. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder following political imprisonment: The role of mental defeat, alienation, and perceived permanent change. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(1), 45–55.

- Gureje, O., Lasebikan, V. O., Kola, L., & Makanjuola, V. A. (2006). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 188, 465–471. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.188.5.465

- Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria. (2020). National Policy for Mental Health Services Delivery.

- Taru, M. Y., Bamidele, L. I., Makput, D. M., Audu, M. D., Philip, T. F., John, D. F., & Yusha’u, A. A. (2018). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Internally Displaced Victims of Boko Haram Terrorism in North-Eastern Nigeria. Jos Journal of Medicine, 12(1), 8–15.

- Ibrahim, U. U., Abubakar Aliyu, A., Abdulhakeem, O. A., Abdulaziz, M., Asiya, M., Sabitu, K., Mohammed, B. I., Muhammad, B. S., & Mohammed, B. I. (2023). Prevalence of Boko Haram crisis related depression and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology among internally displaced persons in Yobe state, north-east, Nigeria. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 13, 100590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100590

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

- Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 748–756. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748

- Yehuda, R., & LeDoux, J. (2007). Response Variation following Trauma: A Translational Neuroscience Approach to Understanding PTSD. Neuron, 56(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.006

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Abdulmalik, J., Kola, L., & Gureje, O. (2016). Mental health system governance in Nigeria: Challenges, opportunities and strategies for improvement. Global Mental Health, 3, e9. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.2

- Gureje, O., Abdulmalik, J., Kola, L., Musa, E., Yasamy, M. T., & Adebayo, K. (2015). Integrating mental health into primary care in Nigeria: Report of a demonstration project using the mental health gap action programme intervention guide. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 242. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0911-3

- Odejide, O., & Morakinyo, J. (2003). Mental health and primary care in Nigeria. World Psychiatry, 2(3), 164–165.

- Haruna, A., Kajumba, M. M., & Kibanja, G. M. (2023). Cultural response to PTSD functional adjustment: Impact of religiosity and spirituality among the Kanuri community of Damaturu Nigeria. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 10(3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000264

- Jegede, A. S. (2005). The Notion of ‘Were’ in Yoruba Conception of Mental Illness. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 14(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.53228/njas.v14i1.284

- Baxter, L., Burton, A., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Community and cultural engagement for people with lived experience of mental health conditions: What are the barriers and enablers? BMC Psychology, 10(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00775-y

- WHO, & Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. (2014). Social Determinants of Mental Health. WHO.

- Coker, T. (2023, April 26). Nigeria’s Mental Health Crisis: A Mind-Boggling Burden on 40 Million Minds. TC Health. https://www.tchealthng.com/thought-pieces/nigerias-mental-health-crisis-a-mind-boggling-burden-on-40-million-minds

- WHO, & Ministry of Health Nigeria. (2006). WHO-AIMS Report on Mental Health System in Nigeria.

- Fromm, M. G. (2021). Psychoanalytic Approaches to Social Trauma. In A. Hamburger, C. Hancheva, & V. D. Volkan (Eds.), Social Trauma – An Interdisciplinary Textbook (pp. 69–76). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47817-9_7

- Iroegbu, S., & Onyedinefu, G. (2022, September 16). Insecurity: Traumatised Ex-War Soldiers Are Ticking Time-Bombs In Nigeria If… –Generals Warn. Global Sentinel. https://globalsentinelng.com/insecurity-traumatised-ex-war-soldiers-are-ticking-time-bombs-in-nigeria-if-generals-warn/

- Butu, H. M., Hashim, A. H., Ahmad, N., & Hassan, M. M. (2023). Influences of Cultural Values, Community Cohesiveness, and Resilience Among Residents in Insurgency-Prone Northeast Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(12), 1447–1464. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v13-i12/20046

- Allen, F., & Nyiayaana, K. (2023). Nigeria: The State of Social Cohesion. Implications for Policy. Conflict Studies Quarterly, 44, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.24193/csq.44.1

- Şar, V., & Öztürk, E. (2007). Functional Dissociation of the Self: A Sociocognitive Approach to Trauma and Dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8(4), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v08n04_05

- Joseph, S., & Williams, R. (2005). Understanding Posttraumatic Stress: Theory, Reflections, Context and Future. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(4), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465805002328

- Abrutyn, S. (2023). The Roots of Social Trauma: Collective, Cultural Pain and Its Consequences. Society and Mental Health, 21568693231213088. https://doi.org/10.1177/21568693231213088

- Subica, A. M., & Link, B. G. (2022). Cultural trauma as a fundamental cause of health disparities. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114574

- Ehlers, A., Wild, J., Warnock-Parkes, E., Grey, N., Murray, H., Kerr, A., Rozental, A., Thew, G., Janecka, M., Beierl, E. T., Tsiachristas, A., Perera-Salazar, R., Andersson, G., & Clark, D. M. (2023). Therapist-assisted online psychological therapies differing in trauma focus for post-traumatic stress disorder (STOP-PTSD): A UK-based, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(8), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00181-5

- Hardarson, J. P., Gudmundsdottir, B., Valdimarsdottir, A. G., Gudmundsdottir, K., Tryggvadottir, A., Thorarinsdottir, K., Wessman, I., Davidsdottir, S., Tomasson, G., Holmes, E. A., Thorisdottir, A. S., & Bjornsson, A. S. (2023). Appraisals of Social Trauma and Their Role in the Development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070577

- Okereke, I. C., Zahoor, U., & Ramadan, O. (2022). Trauma Care in Nigeria: Time for an Integrated Trauma System. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20880

- Dabkana, T. M., Nyaku, F. T., Onuminya, J. E., & Shobode, M. (2022). Trends in Trauma Services: A Review of the Nigerian Experience. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 31(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/NJM.NJM_167_21

- Gohy, B., Ali, E., Van den Bergh, R., Schillberg, E., Nasim, M., Naimi, M. M., Cheréstal, S., Falipou, P., Weerts, E., Skelton, P., Van Overloop, C., & Trelles, M. (2016). Early physical and functional rehabilitation of trauma patients in the Médecins Sans Frontières trauma centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan: Luxury or necessity? International Health, 8(6), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihw039

- Valles, P., Van den Bergh, R., van den Boogaard, W., Tayler-Smith, K., Gayraud, O., Mammozai, B. A., Nasim, M., Cheréstal, S., Majuste, A., Charles, J. P., & Trelles, M. (2016). Emergency department care for trauma patients in settings of active conflict versus urban violence: All of the same calibre? International Health, 8(6), 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihw035

Authors: Ayodele Samuel Jegede (Department of Sociology, Faculty of The Social Sciences, University of Ibadan, Nigeria), Isaac Olawale Albert (Department of Peace, Security and Humanitarian Studies, Faculty of Multidisciplinary Studies, University of Ibadan, Nigeria) and Adeniran Aluko (Department of Peace, Security and Humanitarian Studies, Faculty of Multidisciplinary Studies, University of Ibadan, Nigeria).

Acknowledgements: In addition to drawing on the contributions and inputs from participants of the SSHAP Social Science in Action Workshop this brief was reviewed by Professor Jimoh Amzat (Department of Sociology, University of Sokoto) and Professor Christopher Taiwo Oluwadare (Department of Sociology, Ekiti State University). Editorial support provided by Nicola Ball. This brief is the responsibility of SSHAP.

Suggested citation: Jegede, A. S., Albert, I. O., and Aluko B. A. (2024). Key considerations: Post-trauma impacts in conflict-affected communities in northern Nigeria. Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP). www.doi.org/10.19088/SSHAP.2024.062

Published by the Institute of Development Studies: November 2024.

Copyright: © Institute of Development Studies 2024. This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). Except where otherwise stated, this permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.

Contact: If you have a direct request concerning the brief, tools, additional technical expertise or remote analysis, or should you like to be considered for the network of advisers, please contact the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform by emailing Annie Lowden ([email protected]) or Juliet Bedford ([email protected]).

About SSHAP: The Social Science in Humanitarian Action (SSHAP) is a partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica , CRCF Senegal, Gulu University, Le Groupe d’Etudes sur les Conflits et la Sécurité Humaine (GEC-SH), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, University of Ibadan, and the University of Juba. This work was supported by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and Wellcome 225449/Z/22/Z. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, or the views or policies of the project partners.

Keep in touch

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.socialscienceinaction.org

Newsletter: SSHAP newsletter