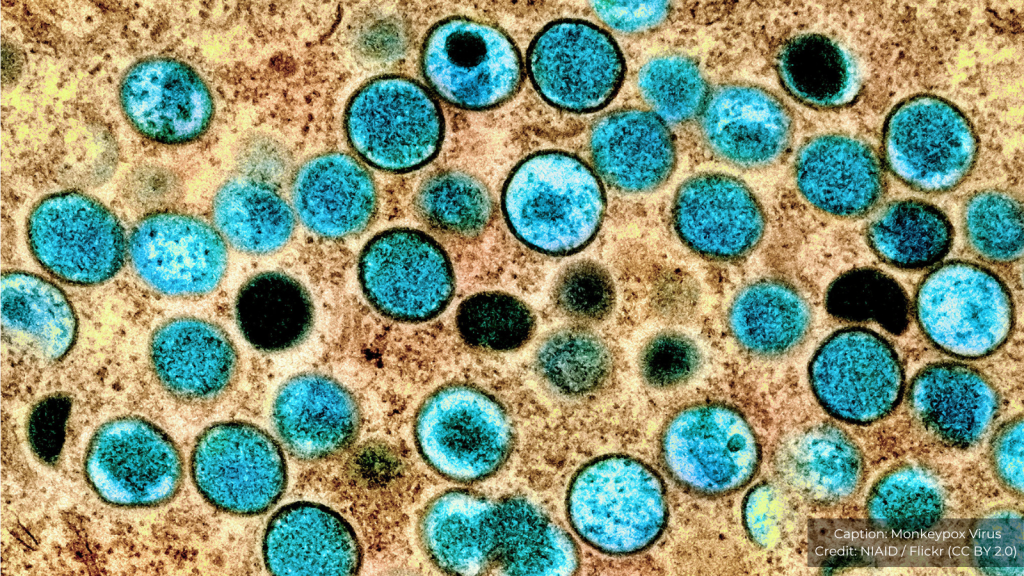

On Thursday 14 August, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared mpox a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) for the second time. A statement released on behalf of the WHO Director General pointed to a concerning increase in cases in recent months of mpox Clade 1, centred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Specifically, a new strain of Clade 1 (identified in Eastern DRC in September last year) has now crossed borders into neighbouring countries where mpox has not been detected before.

Concern about the spread within the African region caused a historic move by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention to use new regional powers to declare an emergency of continental security, prior to the WHO meeting on Thursday. Given the higher case fatality rate than that associated with the previous multi-country outbreak and PHEIC which ended in May 2023 the WHO is clearly also worried about further spread of this more severe form of the disease beyond Africa. The new mutated strain of mpox can be missed by existing diagnostic tools, posing additional challenges to detection. As of Friday 15 August, a case of the new strain has also been reported in Sweden in a person who travelled from Africa.

Framings of disease: the danger of stigma and discrimination

Mpox in DRC has been heterogeneous with respect to the populations affected and involves a mix of zoonotic and human-to-human transmission. It is important to note that the highest mortality to date is in children under 15. However, the new strain is linked also to spread through sexual contact in general, including reports of its presence in same sex networks.

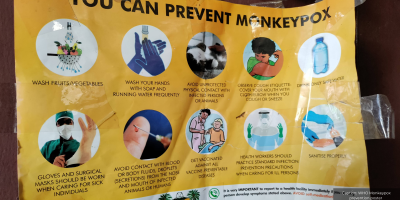

The political milieu in East and Central Africa is extremely hostile towards same sex relations, and anti-queer discourses have been increasing in intensity in recent years. This requires particular sensitivity in public health communications and a heightened ethical responsibility for framing the disease and interventions in ways that do not have unintended consequences through increased discrimination.

Groups at risk in the current outbreak have included people whose livelihoods are linked to transactional sex in the mining regions of South Kivu. The involvement of civil society and activist groups in the co-production of risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) materials is crucial to consider where possible, as is recognition of the hostility of political leaders and the legal environment.

There is much learning to be had from the HIV experience on the continent – as has been seen in a parallel outbreak of the milder Clade 2 mpox in South Africa in recent months, largely amongst gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men (GBMSM) and in association with advanced HIV disease.

In research in Nigeria by IDS and the University of Ibadan in 2022 – 23, we highlighted the heterogeneity of the epidemiology of mpox in Nigeria during the first PHEIC. We also documented the specific concerns of GBMSM in Nigeria. They wished to receive information about the risk of mpox, whilst not being unduly singled out in framings of the disease and RCCE materials. At the time, the difference in this regard to framings of mpox as a sexual health problem in high-income settings through involvement of GBMSM activist networks, was stark. The vulnerability to severe mpox of those with untreated HIV was a concern to colleagues at Nigeria CDC, although the criminalisation of same sex relations and stigma towards ‘key populations’ was acknowledged as a challenge to adequate data collection, fuelling uncertainty about modes of transmission and the burden of disease.

The politics of priorities and neglect

Our research in Nigeria during the first PHEIC in 2022-23 showed that policymakers and frontline public health staff were facing several ongoing outbreaks. In this regard, some reported that mpox at the time was not a particular priority in this context, where historical inequities and structural violence have created a situation where a high burden of endemic disease is a reality and public health resources remain stretched.

At a roundtable in April 2023, panellists from key Nigerian agencies called for health systems strengthening to improve overall outbreak surveillance and care in the country. Some participants also noted a lesson from Covid-19 that underscored the need to improve self-reliance on the continent, including for vaccine production. At the time there were no vaccines or anti-virals for mpox available outside of research settings in Nigeria or elsewhere in Africa – yet the response in high-income countries was dominated by targeted vaccination of high-risk groups, which aided efforts to bring the outbreak under control in these settings.

It is notable that when the first PHEIC for mpox was declared in 2022, senior African public health officials commented that they had flagged an increase in the disease in West Africa for several years; this concern was not picked up by international actors and the Covid-19 pandemic further drew attention away. The first PHEIC was only declared once mpox spread beyond Africa and to high-income settings.

Beyond the politics of priorities across regions, there is an uncomfortable reality that certain lives are persistently valued more than others in prioritising matters for global health response. When the cases of mpox began falling globally, the first PHEIC was ended in May 2023. Mpox continued to cause disease and deaths in Africa. In a statement explaining the decision to end the emergency, WHO pointed to the need instead for “sustained investments”, including in One Health prevention strategies.

The statement continued that the committee that made that decision “emphasised the necessity for long-term partnerships to mobilize the needed financial and technical support for sustaining surveillance, control measures and research for the long-term elimination of human-to-human transmission, as well as mitigation of zoonotic transmissions, where possible.”

A little over a year later as a PHEIC is now declared again, the emergency committee Chair, Professor Ogoina, has reiterated a now familiar refrain calling for greater global solidarity and an end to persistent neglect: “The current upsurge of mpox in parts of Africa, along with the spread of a new sexually transmissible strain of the monkeypox virus, is an emergency, not only for Africa, but for the entire globe. Mpox, originating in Africa, was neglected there, and later caused a global outbreak in 2022. It is time to act decisively to prevent history from repeating itself.”

Global inequities persist

With the declaration of a second PHEIC, WHO has announced new emergency funding for mpox responses in Africa. However, the importance of financing efforts to strengthen systems for pandemic preparedness between discrete ‘emergency’ periods has been underscored yet again. As authors of a Lancet viewpoint stressed in 2023, sustained additional external funding is needed to supplement and support African-led efforts to research and respond to mpox: “Keeping everyone safe will require a global outlook and approach and should always start with addressing the problem where it is endemic and causing the most illness and death.”

The vital need for interdisciplinary perspectives to inform public health interventions

There is still no vaccine roll out in the Democratic Republic of Congo. As responses to mpox have now gained wider attention with the declaration of the PHEIC, the Director-General of the WHO has mobilised emergency use protocols to rachet up efforts to get these distributed within African settings. In Eastern DRC, these efforts will need to be implemented in a context where the suffering associated with this disease is playing out amidst multiple intersecting political, social and economic crises. It offers a sober example of the challenges to humanitarian responses in the midst of conflict, insecurity, displacement, and poor access to healthcare. The UN MONUSCO mission is slated to withdraw this year.

These conditions and the complex and sensitive nature of the mpox situation makes it more imperative than ever that health emergency responses take account not only of the shifting epidemiological evidence, but also of social and political science perspectives, as well as insights from ethicists, in planning and financing the immediate and longer-term responses to mpox.